Siempre he tenido a Chumy Chúmez por uno de los mejores humoristas gráficos españoles de todos los tiempos (y no solo españoles: en 1973, un jurado canadiense lo proclamó el mejor del mundo), pero tengo la impresión de que desde que murió, hace ya 21 años, está un tanto olvidado. Por eso me alegra mucho la reedición por parte de la editorial Pepitas su libro Una autobiografía, publicado por primera vez en 1973. Curiosamente, no se trata de un volumen de viñetas, sino de un relato onírico, freudiano y surrealista confeccionado con collages a partir de recortes de grabados de revistas españolas de finales del siglo XIX y comienzos del XX, como La Ilustración Española y Americana, La Ilustración Artística o La Ilustración Ibérica, una afición de la que el humorista ya había dado muestra en sus colaboraciones en la revista La Codorniz.

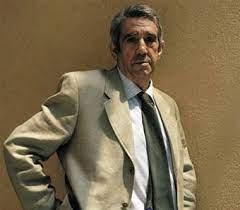

Chumy Chúmez, venido al mundo en la hermosa ciudad española de San Sebastián en 1927 bajo el nombre de José María González Castrillo, cimentó su extraordinaria carrera como humorista gráfico en diarios como Madrid, del que fue el principal editorialista gráfico hasta la suspensión del periódico por la dictadura del general Franco en 1971 (después su sede sería incluso dinamitada), y semanarios como el mítico La Codorniz y el progresista Triunfo.

Autoproclamada “la revista más audaz para el lector más inteligente”, La Codorniz (1941-1978) fue la publicación española de humor más relevante de todo el siglo XX. Había sido fundada por Miguel Mihura, uno de los mejores escritores españoles de humor de todos los tiempos, quien se adelantó veinte años al teatro del absurdo con Tres sombreros de copa, escrita en 1932, aunque no se representó hasta 1952.

A partir de 1972, La Codorniz se vio ampliamente superada por Hermano Lobo, creada precisamente por un Chumy que acababa de dejar la vieja revista fundada por Mihura para practicar un humor más moderno e incisivo. Hermano Lobo llegó a tirar 150.000 ejemplares, mientras que su competidora se estancó en 80.000, prácticamente la mitad.

Para su creación, Chumy estudió detenidamente las principales revistas internacionales de humor de la época y se inspiró muy especialmente en Charly Hebdó –él mismo calificó a Hermano Lobo de “maravilloso casi-plagio” de la publicación francesa–.

En la nueva revista –que llevaba como subtítulo “Semanario de humor dentro de lo que cabe”, en ingeniosa alusión a la censura de la época– lo acompañó una extraordinaria pléyade de humoristas gráficos como Forges, Summers, El Perich, Gila, Ops (heterónimo, por aquel entonces, de Andrés Rábado, hoy El Roto) y el argentino Quino, además de las firmas más audaces del periodismo español del momento: Francisco Umbral, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Eduardo Haro-Tecglen, Cándido, Manuel Vicent, Luis Carandell... Imposible competir con tanto ingenio y tanta osadía. Hermano Lobo –de la que Chumy no pudo ser director porque no tenía el carné de periodista– fue la primera y la más importante de lo que se llamó “el bum de las revistas de humor” en el Tardofranquismo y la Transición española.

Máximo, que, como digo, acompañó a Chumy en Hermano Lobo y luego, en la Transición, haría historia en el diario madrileño El País, resumió en un axioma perfecto el perfecto humor de Chumy: “La inteligencia y el ingenio se dan en Chumy en porcentajes absolutos. De tal modo que en un chiste de Chumy hay un cien por cien de inteligencia y un cien por cien de ingenio: o sea, un doscientos por cien de prodigio, que, si en la aritmética es suma improbable, en el arte es síntesis posible”.

Con Chumy se daba la curiosa paradoja de que siendo un excelente pintor –Forges lo calificó de “el mejor pintor de todos los dibujantes españoles de humor de los últimos 60 años, hermano de Solana, hijo de Zuloaga, nieto de Goya, discípulo de Picasso”–, a algunos les parecía que “dibujaba mal”. Y es que su trazo expresionista, a veces pretendidamente feo –junto a su intuición para la composición (tan importante en la viñeta de humor) y la fuerza de sus manchas negras– desconcertaba a muchos.

Pero Chumy no fue solo dibujante de humor, sino también escritor y director de cine. Nos legó una quincena de libros –entre ellos, este Una autobiografía que ahora reedita Pepitas y Yo fue feliz en la guerra, otra autobiografía con sus recuerdos de la Guerra Civil española– y dos largometrajes de ficción –Dios bendiga cada rincón de esta casa (1977) y ¿Pero no vas a cambiar nunca, Margarita? (1978)– en las que colaboró, en la producción y el guion, su amigo Summers, además de unos cuentos documentales, la mayoría sobre ciudades andaluzas. Inolvidables son también sus numerosas intervenciones como contertulio en programas de radio en los que dejó muestra de una de sus principales señas de identidad: la hipocondría. De hecho, uno de sus libros se titula Cartas de un hipocondríaco a su médico de cabecera (2000).

Yo descubrí a Chumy en mi adolescencia, en el diario El Correo Español, de Bilbao (llamado hoy solamente El Correo) y el suplemento de humor Al Loro, del ABC de Madrid, en el que, entre otros, también colaboraba Summers. Unos años después lo seguí en La Voz de Galicia, de A Coruña, donde gracias a él –pues sus viñetas se publicaban en la misma página– supe de Xaquín Marín, otros de mis humoristas gráficos preferidos, sobre el que tuve el placer de realizar una tesis doctoral hace no mucho. Por cierto que Chumy y Marín se conocieron en 1972 en Hermano Lobo. En realidad, lo que tuvieron fue un encontronazo, pues a Chumy no le pareció oportuno publicar los dibujos de Marín por considerarlos demasiado underground para la línea de la revista. A cambio, este escribió algunos artículos de humor.

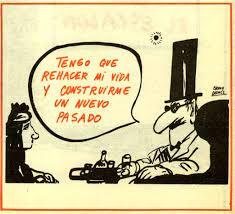

Además de un talento extraordinario, Chumy y Marín siempre han compartido una característica que yo valoro mucho en el dibujo de humor: la intemporalidad de sus viñetas. El propio Chumy lo explicaba así:

“La actualidad no es como los fuegos artificiales, cuya luz dura solo unos instantes. Las noticias españolas duran meses y años. Hay algunas que duran siglos. Las noticias tienen unos desarrollos lentísimos que dan ocasión a los periodistas a sacarles mucho jugo. El paro, por ejemplo […]. Con el terrorismo pasa lo mismo, y lo mismo pasa también con las carreteras y con el infinito número de problemas que tiene España y que tardarán siglos en ser resueltos. Esa es la verdadera actualidad y no la noticia efímera que nace y muere en el mismo día”.

En una de sus viñetas también reflejaba esta misma idea: “Es muy sencillo: la rabiosa actualidad es lo que no se recuerda al día siguiente”.

Por cierto que la primera cita está extraída de un libro verdaderamente increíble: una monografía profesional sobre el humorismo –Ser humorista, se titulaba– publicada por la Fundación Universidad Empresa de Madrid junto a otras muchas sobre profesiones más convencionales, como arquitecto, abogado o médico. Recuerdo que por aquel entonces yo vivía en Santiago de Compostela y me trasladé en autobús hasta A Coruña, a 65 kilómetros de distancia, solo para comprarla en un kiosko de prensa en la que la había descubierto.

La muerte, el poder, la injusticia, la burguesía, los oprimidos, la relaciones de pareja… fueron los temas recurrentes de Chumy. Sus viñetas siempre estuvieron impregnadas de un acentuado humor negro. De un verdadero humor negro: el que se ríe de la muerte, no del muerto.

Un humor negro que hay sin duda en el siguiente relato que extraigo, recortado, de una antología de viñetas y textos del autor que publicó la editorial española Temas de Hoy en 1992 y que me parece, entre bromas y veras, una atinadísima reflexión sobre lo que es el humor:

“… definir el humor es imposible. Por eso […] voy a intentar que ustedes comprendan, por medio de un ejemplo, la esencia de tan complejo problema.

Hagan lo siguiente: cuando estén gozando de la paz serena del hogar, cuando estén todos juntos en casa viendo la televisión […], acérquense a su abuelo y suéltenle una coz o una bofetada de manera que se le salten todos los dientes, o la dentadura postiza […]. Después estudie con la mayor objetividad posible las reacciones de todos los miembros de la familia […].

Los niños pequeños, al ver los dientes […] por el suelo, darán saltos de alegría y decorarán los espacios con sus carcajadas infantiles y sus gritos. Pues bien: eso no es humor […] Es una venganza.

Si su esposa le dice a su suegro: ‘Abuelo, ahora ya tiene usted hueco para que le salga la muela del juicio’, no está tampoco manifestando cierta capacidad para el humor. Su señora solo practica la ironía […].

Si la hija del abuelo, o sea su señora madre de usted, exclama: ‘Ahora ya no tendrás más remedio que tomarte la papilla y dejar los filetes para los demás’, tampoco da muestras de saber lo que es humor, porque solamente expresa una indecorosa forma de sarcasmo impropia de una hija.

Pero si el abuelo exclama con la sonrisa en los labios: ‘Ahí me las den todas’, está dándonos una admirable lección de humor.

Y si, para terminar, el abuelo dice la frase en inglés, pues entonces –mejor que mejor– nos da una culta exhibición de su conocimiento del famoso humor británico […]”.

Me alegro mucho de que el nombre de Chumy Chúmez vuelva a estar en los escaparates de las librerías españolas. Ahora se agradecería también la publicación de una buena antología de viñetas suyas. Fue uno de los más grandes humoristas gráficos españoles de todos los tiempos y, sin duda, uno de los imprescindibles desde mediados de los años 60 del siglo pasado hasta hoy, junto a Mingote, Forges, Máximo, El Perich y El Roto. Sin él, yo habría amado también el humor gráfico, pero no de la misma forma ni con la misma intensidad.

Oh, humor, oh, humor | The return of Chumy Chúmez

By Félix Caballero

I have always considered Chumy Chúmez to be one of the best Spanish cartoonists of all time (and not only Spanish: in 1973, a Canadian jury proclaimed him the best in the world), but I have the impression that since he died, it has been 21 years old, he is somewhat forgotten. That is why I am very happy about the reissue by the Pepitas publishing house of his book Una autobiografía, published for the first time in 1973. Curiously, it is not a volume of vignettes, but rather a dreamlike, Freudian and surrealist story made with collages from of cuttings of engravings from Spanish magazines from the late 19th century and early 20th century, such as The Spanish and American Illustration, The Artistic Illustration or The Iberian Illustration, a hobby that the humorist had already shown in his collaborations in the magazine La Quail.

Chumy Chúmez, who came into the world in the beautiful Spanish city of San Sebastián in 1927 under the name of José María González Castrillo, cemented his extraordinary career as a graphic humorist in newspapers such as Madrid, for which he was the main graphic editorialist until the newspaper's suspension due to the dictatorship of General Franco in 1971 (later its headquarters would even be dynamited), and weeklies such as the legendary La Codorniz and the progressive Triunfo.

Self-proclaimed “the boldest magazine for the most intelligent reader,” La Codorniz (1941-1978) was the most relevant Spanish humor publication of the entire 20th century. It had been founded by Miguel Mihura, one of the best Spanish humor writers of all time, who anticipated the theater of the absurd by twenty years with Three Top Hats, written in 1932, although it was not performed until 1952.

Starting in 1972, La Codorniz was widely surpassed by Hermano Lobo, created precisely by Chumy who had just left the old magazine founded by Mihura to practice more modern and incisive humor. Hermano Lobo managed to print 150,000 copies, while its competitor stagnated at 80,000, practically half.

For its creation, Chumy carefully studied the main international humor magazines of the time and was especially inspired by Charly Hebdó – he himself described Hermano Lobo as a “wonderful near-plagiarism” of the French publication.

In the new magazine – which had the subtitle “Weekly humor within what is possible”, in an ingenious allusion to the censorship of the time – he was accompanied by an extraordinary host of graphic comedians such as Forges, Summers, El Perich, Gila, Ops ( heteronym, at that time, of Andrés Rábado, today El Roto) and the Argentine Quino, in addition to the most audacious firms of Spanish journalism of the moment: Francisco Umbral, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Eduardo Haro-Tecglen, Cándido, Manuel Vicent, Luis Carandell ... Impossible to compete with so much ingenuity and so much daring. Hermano Lobo – of which Chumy could not be director because he did not have a journalist's card – was the first and most important of what was called “the boom of humor magazines” in the late Franco era and the Spanish Transition.

Máximo, who, as I say, accompanied Chumy in Hermano Lobo and later, in the Transition, would make history in the Madrid newspaper El País, summarized Chumy's perfect humor in a perfect axiom: “Intelligence and ingenuity are found in Chumy in absolute percentages. In such a way that in a Chumy joke there is one hundred percent intelligence and one hundred percent ingenuity: that is, two hundred percent prodigy, which, if in arithmetic it is an improbable sum, in art it is a possible synthesis. ”.

With Chumy there was the curious paradox that, being an excellent painter, Forges described him as “the best painter of all the Spanish humor cartoonists of the last 60 years, brother of Solana, son of Zuloaga, grandson of Goya, disciple of Picasso. ”–, to some it seemed that “he drew badly.” And his expressionist line, sometimes supposedly ugly – along with his intuition for composition (so important in humorous vignettes) and the strength of his black spots – disconcerted many.

But Chumy was not only a humorist, but also a writer and film director. He bequeathed us fifteen books – among them, this Una autobiografía that Pepitas is now republishing and I was happy in the war, another autobiography with his memories of the Spanish Civil War – and two feature-length fiction films – God bless every corner of this house ( 1977) and But are you never going to change, Margarita? (1978) – in which his friend Summers collaborated on the production and script, as well as some documentary stories, most of them about Andalusian cities. Unforgettable are also his numerous appearances as a guest speaker on radio programs in which he showed one of his main hallmarks: hypochondria. In fact, one of his books is titled Letters from a hypochondriac to his family doctor (2000).

I discovered Chumy in my adolescence, in the newspaper El Correo Español, from Bilbao (today only called El Correo) and the humor supplement Al Loro, from ABC in Madrid, in which, among others, Summers also collaborated. A few years later I followed him in La Voz de Galicia, in A Coruña, where thanks to him – since his cartoons were published on the same page – I learned about Xaquín Marín, another of my favorite cartoonists, about whom I had the pleasure of making a doctoral thesis not long ago. By the way, Chumy and Marín met in 1972 at Hermano Lobo. In reality, what they had was a clash, since Chumy did not see fit to publish Marín's drawings because he considered them too underground for the magazine's line. In exchange, he wrote some humorous articles.

In addition to an extraordinary talent, Chumy and Marín have always shared a characteristic that I highly value in humor drawing: the timelessness of their cartoons. Chumy himself explained it like this:

“Nowadays is not like fireworks, whose light lasts only a few moments. Spanish news lasts for months and years. There are some that last centuries. The news develops very slowly, which gives journalists the opportunity to get a lot of juice out of it. Unemployment, for example […]. The same thing happens with terrorism, and the same thing also happens with the roads and with the infinite number of problems that Spain has and that will take centuries to be solved. “That is the true news and not the ephemeral news that is born and dies on the same day.”

In one of his vignettes he also reflected this same idea: “It's very simple: the rabid news is what is not remembered the next day.”

By the way, the first quote is taken from a truly incredible book: a professional monograph on humor – Being a Humorist, it was titled – published by the Fundación Universidad Empresa de Madrid along with many others on more conventional professions, such as architect, lawyer or doctor. . I remember that at that time I lived in Santiago de Compostela and I traveled by bus to A Coruña, 65 kilometers away, only to buy it at a newsstand where I had discovered it.

Death, power, injustice, the bourgeoisie, the oppressed, relationships... were Chumy's recurring themes. His cartoons were always impregnated with accentuated black humor. Of true black humor: the one who laughs at death, not at the dead.

There is undoubtedly black humor in the following story that I extract, cut out, from an anthology of vignettes and texts by the author that the Spanish publishing house Temas de Hoy published in 1992 and that seems to me, between jokes and truth, to be a very accurate reflection on what What is humor?

“…defining humor is impossible. That is why […] I am going to try to help you understand, through an example, the essence of such a complex problem.

Do the following: when you are enjoying the serene peace of the home, when you are all together at home watching television [...], go up to your grandfather and kick him or slap him so that all his teeth come out, or his false teeth […]. Then study as objectively as possible the reactions of all family members […].

Little children, upon seeing the teeth […] on the floor, will jump for joy and decorate the spaces with their childish laughter and screams. Well, that's not humor […] It's revenge.

If your wife says to your father-in-law: 'Grandpa, now you have room for your wisdom teeth to come in,' she is not showing any capacity for humor either. His wife only practices irony […].

If your grandfather's daughter, that is, your mother, exclaims: 'Now you will have no choice but to eat the porridge and leave the steaks for the others', she does not show signs of knowing what humor is, because she only expresses a unseemly form of sarcasm unbecoming of a daughter.

But if the grandfather exclaims with a smile on his lips: 'Give it all to me there,' he is giving us an admirable lesson in humor.

And if, to finish, the grandfather says the phrase in English, then – even better – he gives us a cultured exhibition of his knowledge of the famous British humor […]”.

I am very happy that the name of Chumy Chúmez is once again in the windows of Spanish bookstores. Now the publication of a good anthology of his cartoons would also be appreciated. He was one of the greatest Spanish cartoonists of all time and, without a doubt, one of the essential ones from the mid-60s of the last century until today, along with Mingote, Forges, Máximo, El Perich and El Roto. Without him, I would have also loved graphic humor, but not in the same way or with the same intensity.

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)