Nuestro invitado en este “Vis a vis”, el cubano Jorge Sánchez Armas, es alguien que ha publicado en un sinnúmeros de revistas, diarios, semanarios, etc., de Cuba y de países como Argentina, Malasia, Turquía.

Ha realizado 19 exposiciones personales y 25 colectivas, mostrando sus obras en Salones de Cuba y muchísimos otros países.

Ha sido premiado varias veces en Cuba, por supuesto, pero también en Colombia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, Italia y Rumania.

Un gran aval para sentirnos orgulloso de tenerlo en este espacio.

PP: Bueno, Jorge, para los seguidores de Humor Sapiens, ¿puedes presentarte? (Porque quizás mi presentación fue incompleta). ¿Cómo te gustaría que te conocieran, que te recordaran, cuando ya no estemos aquí?

JORGE: Soy Jorge Sánchez Armas, Ingeniero, caricaturista e ilustrador, nacido en la ciudad de Santa Clara, provincia de Villa Clara en el centro de Cuba. Cuando no estemos aquí me gustaría ser simplemente JORGE, que es como firmo mis trabajos, sin mucho lío. Los humoristas gráficos somos como los locutores de radio a quienes solo conocen sus voces. A nosotros nos identifican por los dibujos y la firma. Yo creo que así sería suficiente.

PP: Casualmente, soy ingeniero también y nacido en la ciudad de Matanzas, muy cerca de Santa Clara, donde he pasado mucho tiempo de amor y amistad. Pero hablemos de ti, que para eso te invité. ¿En qué momento decidiste dedicarte al humor?

JORGE: Vengo de una familia de personas muy humildes, de gente trabajadora y sencilla, pero muy feliz y con un gran sentido del humor. En casa siempre había algún chiste en el ambiente, sobre situaciones de vecinos, o algo de la televisión o de las cosas de la casa. Mi padre siempre fue muy bromista y creo que eso lo heredé. Me dediqué profesionalmente al humor en 2016, o sea, hace relativamente poco tiempo, lo que no quiere decir que no lo hiciera antes. De hecho, siempre fui más humorista que cualquier otra cosa. Recuerdo que en mi época de estudiante de secundaria básica por el año 1976, nos llevaban a mí y a dos amigos más, a una publicación que había surgido en Santa Clara en el año 1969, llamada “Melaito”, al calor de una zafra que se acometería en Cuba al año siguiente. Relacionarme con aquellos jóvenes, pero talentosos caricaturistas, fue decisivo para mí. Artistas de la talla de Pedro Méndez, Ajubel, Panchito, Linares y Roland, quienes nos aportaron sus mejores enseñanzas y consejos para nuestro incipiente trabajo en el humor, a ellos les agradezco siempre.

PP: A buenos árboles te arrimaste. Jorge, pero entonces si comenzaste en 2016 profesionalmente, ¡en solo ocho años has logrado ese número de premios y distinciones! Te felicito de todo corazón. Te espera un gran porvenir, amigo mío. Pero volvamos a lo nuestro: ¿empezaste a dibujar sin estilo? Si tuvieras uno, ¿qué estilo sería? ¿Tuviste alguna influencia de caricaturistas nacionales o extranjeros en ese momento? ¿Cómo ha evolucionado tu trabajo a lo largo del tiempo en términos de forma y contenido?

JORGE: Empecé dibujando muy pequeño, sin estilo, eran los años 60 del pasado siglo y la influencia del cómic estadounidense estaba latente en cada rincón de Cuba. Los que más me gustaron por sus líneas y estilos fueron Virgilio, Juan Padrón y Hernán Henríquez. Intentaba encaminar mis trazos con sus maneras maravillosas de representar personajes y los imitaba, los copiaba, reproducía sus dibujos y cuando veía que podía hacerlos, trataba de hacer algunos míos parecidos. Crear mi propio estilo me ha llevado tiempo, en un país con tantos buenos dibujantes, tener una línea que no se pareciera a nadie ha sido tarea de años. Si digo que tengo mi propio estilo, puedo sonar presuntuoso, solo trato que mis dibujos no sean iguales a los de mis colegas del mundo y creo que en ese intento, algo ha salido como propio. Mi paradigma del humor gráfico, desde hace mucho tiempo ha sido el argentino Joaquín Lavado (Quino), su manera de representar los chistes, ese fino sentido del humor, cada dibujo hecho por él es una verdadera clase magistral de arte, historia y filosofía. La riqueza espiritual que transmitía y transmite, para mí han sido esenciales y la influencia es tremenda. Mis dibujos de hoy no se parecen en nada a los de hace 20 años, ni a los de hace 10. Me he tenido que superar mucho ya que no pasé escuela de dibujo ni artes plásticas. Consumo mucho de lo que hacen los artistas de Cuba y el mundo y eso me ha obligado a tener algo mío entre ellos a quienes admiro y admiraré siempre.

PP: Grandes esos personajes que mencionas. Soy fan de ellos. Y te digo que me parece excelente que hayas ido cambiando el estilo, eso es evolucionar. Y otra cosa, ¿qué modo prefieres: dibujar con humor sin palabras o dibujar con textos? ¿Por qué?

JORGE: Prefiero el humor conceptual, sin palabras, ese que sugiere, que no dice con palabras, pero que la gente lee y se lleva no solo una sonrisa sino una enseñanza, una reflexión. Para mí es esencial que la gente no ría solo por reír, me encanta que la gente se haga su propio juicio sobre lo que hago, que tenga opinión, que discuta, que sugiera, que disienta, que discuta. Trabajo mucho el humor político internacional, por la naturaleza editorial de los medios para los que trabajo, lo que me obliga en ocasiones a salirme de esa línea y ponerles textos a los dibujos, hay situaciones que obligan a decir algo en boca de los personajes y al menos intento que sea con el mínimo indispensable de palabras. Se viven tiempos en que sobre todo la juventud casi no desea leer, si pones textos muy largos corres el riesgo de no ser tomado en cuenta. Además, una de las herramientas infalibles del humor gráfico es decir mucho con poco, que el chiste sea un golpe a los ojos del espectador, que el discurso haga pensar, pero que llegue rápido y a cualquier público, desde los más humildes hasta los más elitistas.

PP: Estás muy claro. Es así como dices… Jorge, ¿el humorista nace o se hace?

JORGE: Eso es más o menos como la de qué fue primero si la gallina o el huevo. En mi caso creo que nací haciendo bromas, chistes y que eso lo he ido educando con el tiempo. Hablo de educar porque para hacer humor hay que conocer y estudiar y mientras más nivel cultural y educacional se tenga, pues con mejor conocimiento de causa harás los chistes sin perder la vida en el intento. Tener talento innato para ser humorista no garantiza serlo como profesional. Hay que moldear, transformar, desaprender paradigmas y aprender otros, hay que educar la sensibilidad, hay que meterse en la vida del mundo y estudiar mucho y conocer de qué y por dónde van las cosas. Para mí no basta con nacer humorista, también hay que edificar a ese humorista, pulirlo, darle herramientas psicosociales fundamentales para hacer un buen trabajo.

PP: Lo que me molesta de ti es que no me das oportunidad para debatir nada, porque hasta ahora estoy de acuerdo con todo lo que has dicho. Seguimos entonces. ¿Es más fácil hacer llorar que hacer reír?

JORGE: Eso te lo puedo responder con la obra de Chaplin, ese Genio que en una misma escena sacaba una carcajada estruendosa y a su vez el contexto mismo sacaba lágrimas. Miles de ejemplos con sus películas maravillosas y sus cortos. Si quieres saber cuán fácil es hacer reír o llorar, sugiero ver la película italiana «La vida es bella», del realizador y actor Roberto Benigni. Con cuánta pericia se ríe sobre el tema del Holocausto en la Europa de la segunda Guerra Mundial, en medio de un campo de concentración. Pienso que reír y llorar son emociones que se llevan a flor de piel y depende de la fibra emocional que se toque y con qué intensidad se haga. Depende mucho de las intenciones de quien trata de llevar un mensaje más o menos gracioso. De la misma manera que hay chistes que hacen llorar, hay situaciones difíciles que hacen reír.

PP: ¡Al fin algo para discutir! Claro, no quiere decir que uno de los dos tenga la razón, quizás ambos la tenemos (o ninguno), porque en el arte y en el humor, específicamente, todo es muy subjetivo. Mira, para mí es más fácil hacer llorar, porque en la vida encontramos más tristeza, dramas y tragedias que momentos divertidos. Incluso, existe un lenguaje para hacer humor, independiente del lenguaje de la modalidad artística que sea, algo que no existe en la otra parte. Pero bueno, es un tema para conversar un café o un ron, no ahora en tan poco espacio. Bueno, amigo, ¿para ti, cuáles son los límites del humor, si los hubiera? Y a propósito, ¿fuiste censurado alguna vez? ¿Te autocensuras mucho, poco o nunca?

JORGE: Creo que el humor, como todo en la vida tiene límites. Por ponerte un ejemplo, me han dejado de publicar chistes para defender los derechos de las personas ciegas por parecer que me estaba burlando de ellas, sin embargo, he visto cómo en la misma publicación han aparecido chistes de muy mal gusto llenos de misoginia, violencia y discriminación. Los que nos dedicamos al humor gráfico, casi siempre nos debemos a necesidades editoriales que tienen un propósito que se debe respetar. El humor por naturaleza es transgresor, es atrevido, no es para nada inocente, dice cosas desde la broma que a nadie en su sano juicio se le ocurriría decir en serio. Los humoristas tenemos la obligación social de encontrar la manera de decirlas. Es una especie de azogue psicológico, que como las bolitas que se riegan por el suelo, nadie las puede coger. La censura se la pone uno mismo y por eso decía que hace falta estudiar y leer mucho, tener herramientas para decir lo que supuestamente no se «debe» o lo que la sociedad no desea. El humor se puede saltar las barreras de la censura, lo que hay que ser mejor y más habilidoso que quien las puso. No creo que me autocensure, más bien hay temas que por respeto no los abordo de la manera que lo harían otros, lo hago desde mi opinión y mis conocimientos que pueden ser o no compartidos.

PP: Bueno, que no te permitas hacer ciertos chistes, eso es autocensura. Y es normal y hasta positivo que lo hagas, porque aunque defiendo a muerte la libertad de opinión, cada humorista en su interior debe evitar hacer humor humillando y ofendiendo a otros. La censura externa, esa sí no debería existir, pero existe y para sobrevivir o no vernos afactados, hay que someterse, ¿no? O como dices, ser inteligente para lograr vencerla sin que se de cuenta. Bueno, ¿cómo ves el presente y el futuro del humor gráfico? Tanto en Cuba como en el mundo.

JORGE: Creo que el futuro del humor gráfico tanto en Cuba como en el mundo tiene buena salud y claro que se debe estar al tanto de cuidarla para que no se nos enferme. Cuba tiene muchas limitaciones de recursos para hacerlo, no obstante, los que nos dedicamos a esto en la Isla, intentamos buscar alternativas y el que busca, siempre encuentra. Se continúan llevando a efecto los salones nacionales e internacionales de siempre, con más o menos lucidez y brillo, pero no se han dejado de hacer. Los humoristas cubanos participamos en eventos internacionales que se convocan y hay varios ejemplos de nuestros artistas multipremiados en esas lides, con el más destacado de todos, nuestro Ares, quién tiene en su haber más de 200 premios y un prestigio bien ganado en todo el mundo. Cuba necesita más mujeres que se dediquen al humor gráfico, la pasada Bienal del Humor estuvo dedicada a ellas, participaron algunas, pero no es suficiente, la aspiración sería a que haya muchas como en países de Europa, Asia y Medio Oriente donde el movimiento de mujeres caricaturistas es tremendo. Necesitamos que más jóvenes se sumen a hacer humor gráfico, el relevo de esta generación de hoy, no se ve con mucha claridad.

PP: Eres más optimista que yo, al parecer. Para mí estamos pasando un mal período en el mundo con el cierre de espacios y la Internet no ha resuelto el problema del pago. Claro, hay que tener esperanzas que todo mejorará. Oye, y para sacarme un poco ese pesimismo, ¿podrías contarnos alguna anécdota cómica, curiosa o ingeniosa, que hayas vivido durante tu trayectoria en el humor?

JORGE: Una de las anécdotas más simpáticas me sucedió en la ciudad de Bayamo en una Fiesta de la Cubanía. Había conocido personalmente en la conferencia de prensa previa, a uno de nuestros pianistas y músicos más destacados, respetados y admirados en todo el mundo. No perdí la oportunidad de hacerme una foto junto a él para tenerla de recuerdo. Cuando se inauguró la exposición que llevé al evento el maestro no estuvo por encontrarse dirigiendo los ensayos de la Gala de la Fiesta, pero la segunda noche fui a la galería a ver cómo andaba la afluencia de personas a la expo. Él estaba en el patio y fui a saludarlo, me reconoció y luego de intercambiar saludos, le pregunté si había visto la exposición y me respondió que sí, que estaba «buenísima», a lo que le agregué «es mía, maestro», casi no me dejó terminar con un «¡No jodas, compadre!» y una palabrota que no reproduciré por acá, con una risotada que me contagió entre el asombro y la felicidad, de cómo aquel respetadísimo y fino pianista en un segundo se anuló e hizo salir al cubanazo humilde y bueno que realmente es. Nada, que esa noche el chiste fue suyo y me hizo más feliz que si hubiera sido mío.

PP: Linda anécdota. Gracias. Y para ir cerrando, ¿quieres que te haga una pregunta que no te hice? Si es así, ¿podrías responderla ahora?

JORGE: Me hubiera gustado mucho que me preguntaras mi opinión sobre la Seña del Humor de Matanzas, me hubiera encantado responderte que fue una de las mejores cosas que le han sucedido al humor cubano de todos los tiempos, que fue una mezcla maravillosa del teatro bufo francés e italiano, del bufo cubano y de Les Luthiers. Pero como no me preguntaste…

PP: Te juro que para la próxima te lo pregunto. En serio, muchas gracias por esas generosas palabras sobre La Seña del Humor, grupo que cofundé y dirigí y en el cual me formé como humorista profesional. Bueno, ¿y qué me puedes aconsejar a mí, como humorista?

JORGE: Pelayo, mi único consejo para ti como humorista es que nunca se te vaya a ocurrir dejar de serlo. Así de simple.

PP: Tengo planeado seguir haciendo humor, estudiarlo y promoverlo hasta que la mente y el cuerpo me lo permitan. Gracias por ese consejo-deseo. Y por último, ¿le puedes dirigir unas palabras a los lectores de Humor Sapiens?

JORGE: Mis mejores deseos a todos los lectores de Humor Sapiens, buscar este oasis de inteligencia y genialidad es una opción espectacular. Pepe y todos los que aportan a sus líneas lo hacen con todo el amor y la dedicación del mundo. La buena noticia es que lo consiguen con tremenda frescura. Consuma Humor Sapiens y verá cómo evoluciona su estado de ánimo y su cuerpo se llena de alegría y buenas vibras. Abrazos a todos.

PP: Querido Jorge, primero volver a darte mil gracias por tu tiempo y tu atención. La pasé muy bien en este “vis a vis”. Te deseo mucha salud, suerte y que sigas cosechando éxitos. Un abrazo.

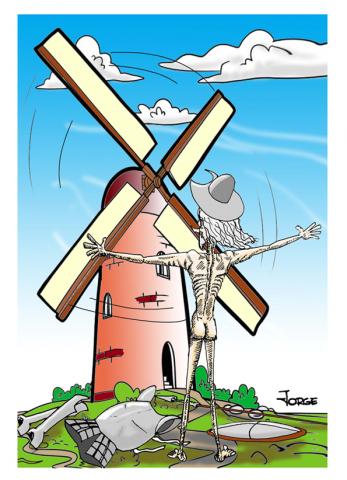

"Changes"

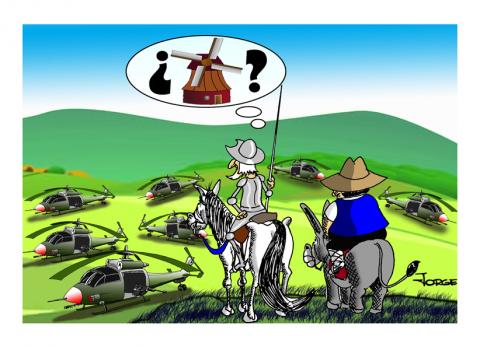

22º Salón Internacional de Caricaturas Antibélicas, Serbia 2023, Premio Diploma del Salón

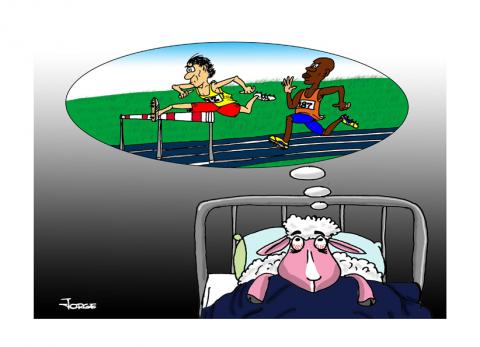

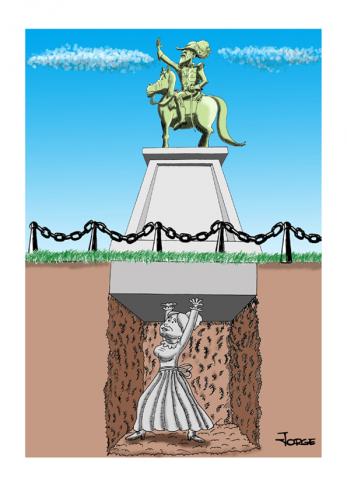

"Counting"

Premio resto del mundo, Premio Internacional De Humor y Sátira Coast To ComixItalia,2023

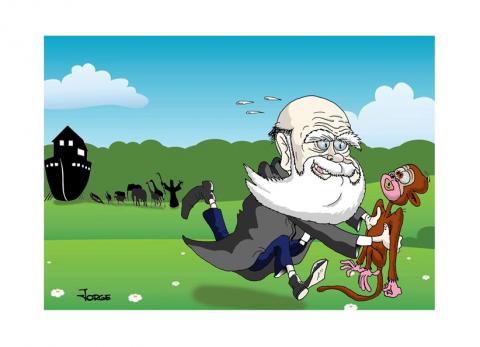

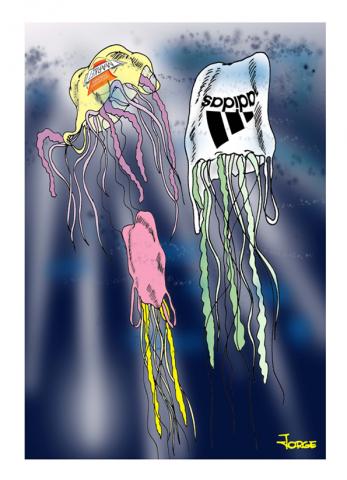

"Darwin to the rescue"

"Fresh"

"Honores"

Segundo premio humor general, Premio del museo del humor, Premio del proyecto Barro sin Berro, 23 bienal de humor gráfico, San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba 2023

"Mutations"

Interview with Jorge Sánchez Armas

by Pepe Pelayo

Our guest in this "Vis a Vis," the cuban Jorge Sánchez Armas, is someone who has published in countless magazines, newspapers, and weeklies in Cuba and countries such as Argentina, Malaysia, and Turkey.

He has held 19 solo exhibitions and participated in 25 group exhibitions, showcasing his work in salons in Cuba and many other countries.

He has been awarded multiple times in Cuba, of course, but also in Colombia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, Italy, and Romania.

A great track record that makes us proud to have him in this space.

PP: Well, Jorge, for the followers of Humor Sapiens, could you introduce yourself? (Because perhaps my introduction was incomplete). How would you like to be known, to be remembered, when we are no longer here?

JORGE: I am Jorge Sánchez Armas, an engineer, cartoonist, and illustrator, born in the city of Santa Clara, Villa Clara province, in central Cuba. When we are no longer here, I would like to be simply JORGE, which is how I sign my works, without much fuss. Graphic humorists are like radio announcers whom people recognize only by their voices. We are identified by our drawings and our signatures. I think that would be enough.

PP: Coincidentally, I am also an engineer and was born in the city of Matanzas, very close to Santa Clara, where I have spent much time surrounded by love and friendship. But let’s talk about you, because that’s why I invited you. When did you decide to dedicate yourself to humor?

JORGE: I come from a family of very humble, hardworking, and simple people, but very happy and with a great sense of humor. There was always some joke in the air at home, about neighbors, something on TV, or things happening in our house. My father was always very playful, and I think I inherited that. I started working professionally in humor in 2016, which is relatively recent, but that doesn’t mean I wasn’t doing it before. In fact, I have always been more of a humorist than anything else. I remember that in my early secondary school years, around 1976, two friends and I were taken to a publication that had emerged in Santa Clara in 1969 called “Melaito,” during the sugarcane harvest effort that Cuba was about to undertake the following year. Engaging with those young but talented cartoonists was a defining moment for me. Artists of the caliber of Pedro Méndez, Ajubel, Panchito, Linares, and Roland shared their best teachings and advice with us for our budding work in humor, and I will always be grateful to them.

PP: You surrounded yourself with great mentors. But Jorge, if you only started professionally in 2016, you’ve achieved all these awards and distinctions in just eight years! I wholeheartedly congratulate you. A great future awaits you, my friend. But let’s get back to our topic: Did you start drawing without a style? If you had one, what would it be? Were you influenced by national or foreign cartoonists at that time? How has your work evolved over time in terms of form and content?

JORGE: I started drawing at a very young age, without a defined style. It was the 1960s, and the influence of American comics was present in every corner of Cuba. The artists I admired most for their lines and styles were Virgilio, Juan Padrón, and Hernán Henríquez. I tried to follow their amazing ways of representing characters—I imitated them, copied them, reproduced their drawings, and when I saw I could do it, I tried to create my own similar ones. Developing my own style took time. In a country with so many great cartoonists, having a distinct line that didn’t resemble anyone else's was a task that took years. If I say I have my own style, I might sound presumptuous—I just try to make my drawings different from those of my colleagues worldwide, and I believe that in that effort, something unique has emerged.

My paradigm in graphic humor has long been the Argentine artist Joaquín Lavado (Quino). His way of presenting jokes, his fine sense of humor—every drawing of his is a true masterclass in art, history, and philosophy. The intellectual depth he conveyed and still conveys has been essential to me, and his influence is tremendous. My drawings today look nothing like those from 20 or even 10 years ago. I have had to improve a lot since I never attended a drawing or fine arts school. I consume a lot of what artists from Cuba and the world create, which has pushed me to develop something of my own among those I admire and will always admire.

PP: Those are great artists you mentioned. I’m a fan of them too. And I think it's excellent that your style has evolved—this is growth. One more thing: do you prefer drawing humor without words or with text? Why?

JORGE: I prefer conceptual humor, wordless, the kind that suggests rather than states, where people can read into it and not just laugh but also take away a lesson or a reflection. For me, it’s essential that people don’t just laugh for the sake of laughing—I love when they form their own opinions about my work, when they engage in discussions, when they suggest or disagree. I work a lot in international political humor because of the editorial nature of the media I work for, which sometimes forces me to add text to drawings. Some situations require characters to say something, and I try to use the bare minimum of words. We live in a time when young people, in particular, are less inclined to read—if you include long texts, you risk being ignored. Also, one of the infallible tools of graphic humor is to say a lot with very little, for the joke to be a punch to the viewer’s eyes, for the message to be thought-provoking but delivered quickly and effectively to any audience, from the most humble to the most elite.

PP: You are very clear. That’s exactly how it is… Jorge, are comedians born or made?

JORGE: That’s a bit like the question about what came first, the chicken or the egg. In my case, I think I was born making jokes and playing pranks, and over time, I’ve been refining that. I say "refining" because making humor requires knowledge and study. The more cultural and educational background you have, the better you can craft jokes without getting yourself into trouble. Having an innate talent for comedy doesn’t guarantee you’ll be a professional comedian. You have to shape it, transform it, unlearn certain paradigms, and learn others. You need to refine your sensitivity, immerse yourself in the world, study, and understand the topics you're addressing. In my opinion, being born funny is not enough—you also have to build and polish that comedian, giving them the essential psychosocial tools to do a good job.

PP: What annoys me about you is that you don’t give me a chance to argue because, so far, I agree with everything you’ve said. Let’s keep going. Is it easier to make people cry than to make them laugh?

JORGE: I can answer that with Chaplin’s work—he was a genius who could make you burst out laughing and tear up in the same scene. There are countless examples in his amazing movies and shorts. If you want to understand how easy or hard it is to make people laugh or cry, I suggest watching the Italian film Life is Beautiful by director and actor Roberto Benigni. It masterfully blends comedy with the tragedy of the Holocaust in World War II, right in the middle of a concentration camp. I believe laughter and tears are emotions that lie just beneath the surface, and it depends on which emotional chord you strike and how intensely you do it. It also depends a lot on the intentions of the person delivering the message—some jokes make people cry, and some difficult situations make people laugh.

PP: Finally, something to debate! Of course, that doesn’t mean one of us is right—maybe we both are (or neither of us is) because art and humor, in particular, are very subjective. For me, making people cry is easier because life is filled with more sadness, drama, and tragedy than fun moments. Humor has its own language, regardless of the artistic medium, but there isn’t a specific "language" for tragedy. Anyway, that’s a conversation for coffee or rum, not for such a short space here. Moving on, what do you think are the limits of humor, if any? And by the way, have you ever been censored? Do you censor yourself a lot, a little, or never?

JORGE: I think humor, like everything in life, has limits. For example, I’ve had jokes rejected because they were seen as offensive to blind people, even though my intent was never to mock them. Meanwhile, I’ve seen jokes in the same publication that were full of misogyny, violence, and discrimination. Those of us who work in graphic humor often have to adhere to editorial guidelines that serve a specific purpose, and that must be respected. Humor is, by nature, transgressive and bold—it’s never innocent. It says things in a joking way that no one in their right mind would dare say seriously. As humorists, we have a social responsibility to find ways to say these things. Humor is like mercury balls that scatter across the floor—no one can quite catch them. Censorship often comes from within; that’s why I said it’s important to study and read a lot, to have the tools to say what "shouldn’t" be said or what society doesn’t want to hear. Humor can bypass censorship, but you have to be smarter and more skillful than those who enforce it. I wouldn’t say I self-censor—I simply choose to approach certain topics in a way that aligns with my perspective and knowledge, whether others agree with it or not.

PP: Well, choosing not to make certain jokes is self-censorship. And that’s normal—even positive—because while I fiercely defend freedom of speech, every comedian must avoid humor that humiliates or offends others. External censorship, on the other hand, shouldn’t exist—but it does. To survive or avoid problems, we either have to submit to it or, as you said, be clever enough to outsmart it. So, how do you see the present and future of graphic humor, both in Cuba and worldwide?

JORGE: I think the future of graphic humor, both in Cuba and globally, is in good health, but we must take care of it so it doesn’t deteriorate. Cuba faces many resource limitations for producing it, but those of us dedicated to this craft always look for alternatives—and when you search, you find. National and international humor festivals continue to take place, sometimes with more or less brilliance, but they haven’t stopped. Cuban humorists participate in global competitions, and many of our artists have won multiple awards. The most outstanding of all is Ares, who has won over 200 awards and gained great international prestige. However, Cuba needs more women in graphic humor. The last Humor Biennial was dedicated to them, and although some participated, it wasn’t enough. The goal is to have many more, as is the case in some European, Asian, and Middle Eastern countries, where female cartoonists are thriving. We also need more young people to join the world of graphic humor—the generational transition is not looking very clear at the moment.

PP: You’re more optimistic than I am. I think we’re going through a tough period worldwide, with media spaces shutting down, and the internet hasn’t solved the issue of financial compensation. Of course, we must have hope that things will improve. Hey, to lift my spirits a little, could you share a funny, curious, or clever anecdote from your career in humor?

JORGE: One of the funniest things happened to me in Bayamo during the Fiesta de la Cubanía. I had met one of our most renowned pianists and musicians at a press conference. I didn’t miss the chance to take a picture with him as a keepsake. During the event’s opening night, he couldn’t attend because he was directing rehearsals for the gala. The second night, I went to check on my exhibition, and I saw him in the courtyard. I greeted him, and he recognized me. After some small talk, I asked if he had seen the exhibition. He said, "Yes, it’s amazing!" and I added, "It’s mine, Maestro." He barely let me finish before blurting out, "No way, man!" followed by an expletive I won’t repeat here, along with a burst of laughter. I was caught between surprise and happiness—it was incredible to see such a prestigious and refined pianist instantly reveal his humble, fun-loving Cuban side. That night, the joke was his, and it made me happier than if it had been mine.

PP: Great anecdote! Thank you. And to wrap up, is there a question I didn’t ask that you would have liked to answer?

JORGE: I would have loved for you to ask my opinion about La Seña del Humor de Matanzas. I would have told you it was one of the best things to ever happen to Cuban humor—a wonderful mix of French and Italian farce, Cuban bufo theater, and Les Luthiers. But since you didn’t ask…

PP: I swear I’ll ask you next time! Seriously, thank you for your kind words about La Seña del Humor, the group I co-founded and directed, where I developed as a professional comedian. Finally, what advice do you have for me as a humorist?

JORGE: Pelayo, my only advice to you as a comedian is: never stop being one. It’s that simple.

PP: I plan to keep making, studying, and promoting humor for as long as my mind and body allow. Thank you for that wish-advice. And finally, do you have any words for the readers of Humor Sapiens?

JORGE: My best wishes to all the Humor Sapiens readers! Seeking out this oasis of intelligence and brilliance is a fantastic choice. Pepe and everyone involved in it put their hearts and dedication into every line. And the good news is—they succeed, with incredible freshness. Enjoy Humor Sapiens, and you’ll see how your mood improves, filling your life with joy and good vibes. Hugs to all!

PP: Dear Jorge, first of all, thank you again for your time and attention. I had a great time in this "face-to-face" chat. I wish you health, luck, and continued success. A big hug.

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)