Félix Caballero Wangüemert (Logroño, La Rioja, 1967) reside en Galicia desde 1991. Es doctor por la Universidad de Vigo y licenciado en Ciencias de la Información por la Universidad de Navarra. Trabajó como periodista en "El Correo Gallego", "Riadevigo.com" y "España Exterior". Es autor de los libros de unos cuantos libros (verán muchos al. final de este texto).

Esos datos son los que uno encuentra “googleando”. Como se ve en el resumido, pero contundente curriculo, es un honor tenerlo en este “vis a vis con la vis cómica”.

Pero además, tenemos una amistad. Recuerdo que en 2016 un amigo en común, Francisco Puñal, nos puso en contacto. Nos carteamos, nos enviamos textos y -si no me equivoco-, en julio del año 2023 comenzó a publicar una sección fija con nosotos llamada “Ay, humor, ay, humor”.

Pero además, tuvimos el placer de conocernos “en vivo” ese año, cuando fui a Vigo, Galicia, donde nos juntamos él, Francisco Puñal, mi hijo Alex y yo en una entretenidísima tertulia café y humor mediente.

Así que esperando otro encuentro, llega este vis a vis.

Comienzo.

PP: Amigo mío, creo que no te presenté debidamente, quizás muchos datos, así que me gustaría que te presentaras tú y de paso me dijeras cómo te gustaría que fueras recordado.

FÉLIX: Soy periodista, pero más que como periodista me gusta definirme como “polígrafo”, en el sentido que se daba antes a esta palabra: persona que escribe sobre varias materias. Ya sabes que hoy “polígrafo” se usa más bien como sinónimo de la “máquina de la verdad”. Y sí, soy humorista, pero no tanto porque haga humor sino porque miro la vida con humor, aunque a veces, sí, creo humor, lo investigo o lo divulgo. ¿Que cómo me gustaría ser recordado? Con dificultad, como un recuerdo lejano y algo borroso. No, en serio: como una buena persona, aunque aún no lo sea. Estoy en ello.

PP: Por lo que sé de ti, eres buena persona y por lo que leo tuyo, sin dudas eres humorista y estudioso del humor también. Dime algo, ¿te gusta que te hagan entrevistas?

FÉLIX: No, en realidad lo odio, o más bien lo temo. Supongo que al final el problema es mi inseguridad, el miedo a quedar como un idiota. También influye el hecho de que sea periodista: los periodistas nos formamos para preguntar, no para responder, y en todo caso nos sentimos más cómodos preguntando que respondiendo. Aunque te confieso que hay una parte de mí lo suficientemente vanidosa como para que, en el fondo, no deje de halagarme.

PP: Tenemos que quitarnos los miedo. Claro, yo me los quité mucho, porque mi frescura y descaro es demasiado, ya que sin ser periodista, “entrevisto a un entrevistador sin saber entrevistar” (disculpa el intento de trabalenguas). Pero por tal motivo esto le llamo “vis a vis”, para más que una supuesta entrevista, sea una conversación relajada. Pero comencemos, ¿cómo llegaste a interesarte en la creación, la investigación y el estudio del humor?

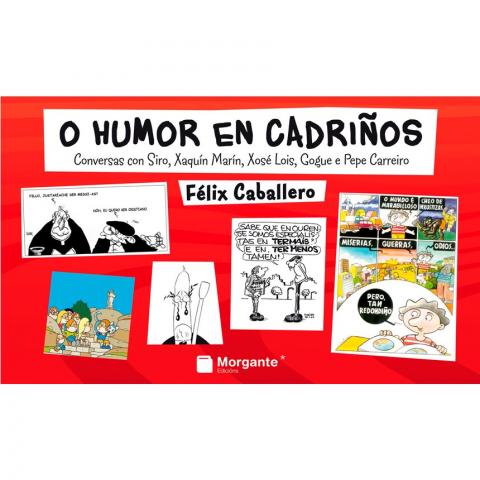

FÉLIX: Por la divulgación del humor creo que me interesé desde muy pronto, tanto como por la posibilidad de hacer (o de intentar hacer) humor yo mismo. Pero por la investigación y el estudio de un modo mínimamente sistemático y académico del humor fue hace relativamente poco, a partir de realizar mi tesis doctoral en Comunicación, que centré en la obra del humorista gráfico y dibujante gallego Xaquín Marín.

PP: Si entraste en el campo del estudio del humor, como hiciste, tuviste que llegar a definiciones por ti mismo. Así que te pregunto, ¿qué es para ti el humor? (Me refiero a tu definición del mismo, qué significa).

FÉLIX: Cuando hablamos de humor, tenemos que diferenciar tres grandes formas: la comicidad, la sátira y el humorismo. Casi todo el mundo entiende más o menos lo que son la comicidad y la sátira, géneros, por otro lado, casi tan antiguos como el hombre. La pregunta del millón es en qué consiste el humorismo. PGarcía, pseudónimo de José García Martínez-Calín, uno de los mejores escritores de “La Codorniz”, quizás la revista de humor española más importante del siglo XX, dice que “el humorismo es el estilo que, mediante la trivialización de lo cargado de seriedad manipuladora, busca la libertad espiritual del receptor a través de la sonrisa”. Me parece una buena definición, pero como me preguntas por la mía, te diré que para mí el humor, entendido como humorismo, es un método para comprender la realidad y defendernos eventualmente de ella. En este sentido, es una actitud ante la vida, casi una filosofía, una forma de mirar y de ver la realidad, intentando descubrir en ella lo que tiene de incongruente, de absurdo, de divertido, de optimista, con la particularidad de que el humor está tanto en el que mira como en lo mirado. Y también un escudo protector, un arma defensiva (tal vez incluso un manual de autoayuda). En mi caso, creo que me viene por mi personalidad reflexiva, pero también insegura y dubitativa. Al final, a uno no le queda más remedio que reírse de sí mismo, y a partir de ahí, de todo.

PP: Paradoja. Estoy muy de acuerdo contigo en tus argfumentos, pero en desacuerdo con la clasificación. Para mí no existe el humor sin comicidad y la sátira, como la ironía, la parodia, etc., son formas dentro de un gran paraguas que es el humor. Por lo tanto, te invito a debatir todo este enredo “en vivo” cuando nos volvamos a ver, ¿de acuerdo? Porque aquí no tenemos espacio para el tema. Pero sigamos. ¿Cuál es el tipo de humor que te gusta consumir? ¿Es el mismo humor que gusta crear? Te lo digo porque, por ejemplo, a mí me gusta consumir la buena sátira política, pero soy mal creando en esa modalidad.

FÉLIX: En general, tanto como creador como como consumidor, me gusta más la comicidad y el humorismo que la sátira, porque la sátira me resulta demasiado agresiva. Pero a veces también se me ocurre alguna sátira política, no sé si buena o mala. En definitiva, no desdeño en absoluto, sino todo lo contrario, el humor blanco, el humor por el humor, que, como sabes, para algunos tiene mala prensa, porque lo consideran descomprometido. Concretando más, te diré que creo que mi humor es muy irónico, pero nada sarcástico. Ya te he dicho que la sátira me resulta un tanto agresiva. Lo que sí es un humor provocativo, pero no ofensivo, sino lúdico. Y loco. Lo que busco es provocar que mi interlocutor se sume al juego y a la locura que le propongo. Cuando encuentro ese tipo de cómplice, es maravilloso. Y luego, otra característica de mi humor es que es muy verbal. Me encantan los juegos de palabras. Cuando se habla de las funciones del lenguaje (referencial, expresiva, póética, apelativa…), siempre añado: “Y lúdica”. El lenguaje puede ser muy lúdico.

PP: Bueno, para mí el humor político es usado mucho para hacer sátira, pero se puede hacer sátira con todo. Según mi molesta opinión, la sátira es usar el humor para reírnos mientras criticar algo, pero constructivamente, sin ofender. El humor que ofende, irrespeta, agrede, humilla, aunque sea de buena elaboración artística, lo considero de tercera categoría (si es que es humor). Y no lo veo como sátira. Ni siquiera como humor negro, como algunos le dicen. Y soy de los que defiende el humor blanco para pensar y para reír por reír también. Para mí todos los tipos de humor tienen el mismo valor. Y por último, somos gemelos en eso del gusto por el juego de palabras. No puedo vivir sin ellas. Y ahora cuéntame, ¿cuáles son los humoristas que más te gustan entre los vivos y fallecidos y españoles y extranjeros? ¿Cuáles han sido los que crees que influyen en tu forma de crear?

FÉLIX: ¡Buf! Sería una lista interminable, porque además, los campos de la creación del humor son muchos: literatura, cine, teatro, música, humor gráfico… Pero, en fin, ahí van algunos nombres: Los Payasos de la Tele (Gaby, Fofó y Miliki), Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Laurel y Hardy, los hermanos Marx, Woody Allen, Billy Wilder, Cantinflas, Rafael Azcona, Enrique Jardiel Poncela, Álvaro Cunqueiro, Castelao, Quino, Francisco Ibáñez, Tip y Coll, Gila, Tricicle, Les Luthiers… Como escritor, no tengo muy claro quién ha podido influir en mí. Lo que sí te diré es que cuando empecé a hacer viñetas de humor (un campo en el que nunca me metí de lleno y bien que lo lamento), estaba muy influido por el humor negro de Chumy Chúmez. Incluso tengo una anécdota al respecto de la que me enorgullezco. Él y yo llegamos a publicar casi la misma viñeta, pero yo la publiqué un año antes. En la mía, un hombre le decía a otro: “Soy pobre, pero honrado”. Y el otro le replicaba: “Las desgracias nunca vienen solas”. La de Chumy reproducía casi el mismo diálogo: “–Yo soy pobre, pero honrado. –Lo comprendo. Las desgracias nunca vienen solas”. Sé que se trató de una mera coincidencia –a los dos se nos ocurrió lo mismo, sin más–, pero a mí me gusta bromear con que el gran Chumy me plagió.

PP: En una ocasión, con mi grupo cubano “La Seña del humor”, actuamos frente a Les Luthiers en La Habana en un homenaje que le dieron. Y al final nos pusimos a conversar con ellos en el cóctel y Marcos Mundstock me dijo que “tal” chiste nuestro que vio, lo habían hecho ellos hacía cinco años. Me puse rojo de vergüenza al darme cuenta que podía pensar que los plagiamos. Marcos se dio cuenta y me dijo. “No te preocupes, a cualquiera se le ocurre el mismo chiste. Nos ha sucedido”. No sé si lo hizo paternalmente, pero lo tomé como la enseñanza de un Maestro. Así que si Marcos lo dice, díselo al gran Chumy Chúmez cuando lo veas en la otra vida, si la hubiera. Bueno, vuelvo a las preguntas: ¿qué te gusta más, ¿crear humor o analizarlo, reseñarlo, “teorizarlo”?

FÉLIX: Crearlo, aunque analizar el humor –intentar descubrir los mecanismos que nos hacen reír o sonreír– tiene su interés y su atractivo, y eso que muchos dicen –y no les quito razón– que intentar explicar el humor es antihumorístico. Y, por supuesto, reseñarlo o divulgarlo también da mucho placer.

PP: En mi caso coinncido contigo. Me da placer estudiar el humor y no lo encuentro antihumorístico, ni mucho menos. En fin, ellos se lo pierden. Y como creador, ¿piensas que es más fácil hacer llorar que hacer reír?

FÉLIX: Sí. Para hacer llorar a alguien basta con pisarlo, mientras que para que se ría tienes que hacerle cosquillas. Ahora en serio: sí, creo que hacer llorar –es decir, hacer emocionarse a los demás hasta las lágrimas– puede ser más fácil que hacer reír, aunque no le quito mérito. Siempre he desconfiado de los críticos de cine o de literatura (hay muchos) que acusan de “tramposa” y de hacer “chantaje emocional” a cualquier obra capaz de tocarnos la fibra sensible, porque muchas nos emocionan de verdad, y ese tiene que ser el objetivo de buena parte del cine y de la literatura. Pero es cierto que algunas obras sí hacen ese tipo de trampas. Efectivamente, se puede conseguir que el espectador llore chantajeándolo emocionalmente, pero es imposible hacer que se ría de esa manera. Además, cuando alguien se ríe sin verdadera gana, cuando finge la risa para complacer a su interlocutor, se nota mucho y resulta francamente penoso.

PP: En síntesis, mi opinión: hacer buen arte es difícil sea tragedia o comedia. Pero hacer llorar es más fácil, quizás porque en la vida real abundan mucho más las tragedias y los dramas que las comedias. Otro punto: existen técnicas, axiomas, existe un lenguaje para crear humor, no así para hacer provocarnos emociones negativas. Y ahora una pregunta de moda: ¿Cuáles serían los límites del humor si los hubiera?

FÉLIX: Yo tengo claro que sí los hay, de la misma forma que, como periodista, tengo claro que el derecho a la información tiene límites en el derecho a la intimidad y al honor. Los límites del humor son, por supuesto, el Código Penal, y después el buen gusto. Se puede bromear de todo, pero no de cualquier manera. Se trata de que la risa añada algo de alegría, dulzura o ligereza a la miseria del mundo y no más odio o sufrimiento. El chiste antijudío que reímos y aplaudimos en boca de un judío siempre será reprobable en los labios de un antisemita.

PP: De acuerdo total. Existen límites externos, como el Código Penal que mencionas y que sería muy severo si se trata de una dictadura, o sería muy severo en lo moral, si en el poder social imperan minorías fanáticas y en el interno todo eso con nuestros principios manejan la autocensura, ¿no es cierto? Pero cambiemos “la onda” ¿Puedes contar alguna anécdota graciosa, curiosa o ingeniosa que hayas vivido relacionada con tu trabajo en el humor?

FÉLIX: Graciosa o ingeniosa no es, solo curiosa: siempre he valorado mucho a los payasos y llegué a hacer mis pinitos en este sentido, hace muchos años, en formato dúo junto a mi amigo Héctor Barrera, un actor y maestro de actores hispano-argentino. Actuamos con el nombre de Cuarto y Mitad en el Teatro Principal de Pontevedra (España) en el Festiclown, el festival internacional de payasos que se celebró durante varios años en esa ciudad gallega. Había actuaciones de profesionales y aficionados, y talleres de clown impartidos por figuras de relevancia internacional como Jango Edwards o Leo Bassi. Por cierto que nos acompañó a la guitarra Xoán Curiel, que hoy es uno de los cantautores gallegos más importantes.

PP: No conocía esa faceta tuya, Félix. Te felicito. Eres un todoterreno en el humor: actúas, escribes, dibujas y eres un estudioso y promotor del humor. ¡No se puede ser más humorista, amigo mío! Bueno, sobre este punto, ¿qué te gustaría hacer dentro del humor que no hayas hecho?

FÉLIX: Me gustaría hacer humor gráfico y publicarlo de forma continuada. Y también humor escénico. Sería feliz subiendo cada fin de semana a un escenario, por pequeño que fuese, y contar “mis cosas”. En los dos campos he hecho mis pinitos, pero nada más. En la literatura, tal vez escribir y publicar algún libro de relatos humorísticos. Y retomar el género de mis dos primeros libros, que alguno llamó “greguerías”, aunque no llegaban al ingenio de Ramón Gómez de la Serna y se quedaron en meros chistes verbales. Y escribir comedia: si hubiese nacido treinta años antes, para el teatro y el cine; y si hubiera nacido treinta años después, para la televisión y las redes sociales.

PP: No creo que te sea tan difícil cumplir esas metas. Talento tienes de sobra. Y para ir cerrando, ¿se te ocurre alguna pregunta que te hubiese gustado que te hiciera y no te hice? Si es así, ¿la puedes responder ahora?

FÉLIX: Quizás alguna de geografía, para poder lucirme, porque soy un hacha en la materia, pero mejor una pregunta de nivel elemental, no vaya a acabar haciendo el ridículo. Y ahora en serio: no, no se me ocurre ninguna pregunta más para que me hagas, pero sí quiero formular yo –para reflexión de todos– una que cada vez me hago más: ¿por qué la mayoría de la gente llama sistemáticamente “malos” a todos los chistes basados en juegos de palabras? Lo digo por experiencia propia: ya te he dicho que me encanta hacer chistes de este tipo. A mí me parece lo contrario: que muchos de ellos (y no hablo de los míos, claro; sería inmodestia) son francamente “buenos”, porque denotan un ingenio notable. ¿Qué entenderá por chistes “buenos” esta gente?

PP: Te puedo dar mi respuesta (sin estar seguro, claro). Para mí hacer humor inteligente es cuando el consumidor se siente inteligente al descifrar la elaboración artística que el humorista le propone para hacerlo reír o sonreír. Un chiste fácil, sencillo, que lo entiende todo el mundo, no es por tanto un humor muy inteligente que digamos. Para los juegos de palabras (buenos y malos), el creador tiene que pensar, dominar la lengua, tener sentido lúdico y del humor para hilvanar pensamientos, sensaciones, asociaciones para crearlos. Es difícil hacer juegos de palabras. Hay que tener el cerebro “engrasado”. Así como es difícil que los acepten los consumidores, cuando se está acostumbrado al humor fácil, básico, u ofensivo o vulgar. Otra cosa es la cuestión de gustos. Por ejemplo, yo puedo entender que es muy bueno un chiste y no gustarme por otras razones. Pero no puedo decir que es malo. Recuerda que un chiste que no de gracia en Tumbuctú, lo haces en Remangalatuerca y allí pueden llorar de la risa. Y el juego de palabras es un chiste. En fin, estoy seguro que el humor blanco es más difícil de hacer que cualquier otro. Ya dejé de hacerles caso a esa gente que menosprecian los juegos de palabras, el arte por el arte, la risa por la risa.

Y ahora sí para terminar: ¿le podrías dedicar unas palabras a los lectores de Humor Sapiens?

FÉLIX: Solo felicitarles por el inmenso privilegio que tienen de poder disfrutar de un espacio dedicado al humor como no creo que haya muchos en el mundo.

PP: Millones de gracias por esa valoración, millones de gracias por tu generosidad al aceptar este “vis a vis”, millones de gracias por colaborar tanto con Humor Sapiens y millones de gracias por existir y conocerte. Me despido deseándote mucha salud y muchos éxitos.

FÉLIX: Pues yo también me despido de ti y de todos los lectores de Humor Sapiens. Muchas gracias por acogerme en este maravilloso lugar, en el que llevo ya más de un año colaborando, y por mostrarte siempre tan generoso y cariñoso conmigo.

Inteview with Félix Caballero

By Pepe Pelayo

PP: My friend, I think I did not properly introduce you, perhaps too much information, so I would like you to introduce yourself and tell me how you would like to be remembered.

FÉLIX: I am a journalist, but more than as a journalist I like to define myself as a “polygrapher”, in the sense that this word was given before: a person who writes about various subjects. You already know that today “polygraph” is used more as a synonym for the “truth machine.” And yes, I am a comedian, but not so much because I make humor but because I look at life with humor, although sometimes, yes, I create humor, I investigate it or disseminate it. How would I like to be remembered? With difficulty, like a distant and somewhat blurry memory. No, seriously: like a good person, even if I'm not one yet. I'm on it.

PP: From what I know about you, you are a good person and from what I read about you, you are undoubtedly a comedian and a student of humor as well. Tell me something, do you like being interviewed?

FÉLIX: No, actually I hate it, or rather I fear it. I guess in the end the problem is my insecurity, the fear of looking like an idiot. The fact that you are a journalist also influences: journalists are trained to ask, not to answer, and in any case we feel more comfortable asking than answering. Although I confess that there is a part of me that is vain enough that, deep down, I can't stop flattering myself.

PP: We have to get rid of our fears. Of course, I took them off a lot, because my freshness and impudence is too much, since without being a journalist, “I interview an interviewer without knowing how to interview” (sorry for the tongue twister attempt). But for this reason I call this “vis a vis”, so that more than a supposed interview, it is a relaxed conversation. But let's start, how did you become interested in the creation, research and study of humor?

FÉLIX: I think I became interested in the dissemination of humor from very early on, as much as in the possibility of making (or trying to make) humor myself. But due to the research and study of humor in a minimally systematic and academic way, it was relatively recently, after completing my doctoral thesis in Communication, that I focused on the work of the Galician graphic humorist and cartoonist Xaquín Marín.

PP: If you entered the field of studying humor, as you did, you had to come up with definitions for yourself. So I ask you, what does humor mean to you? (I mean your definition of it, what does it mean).

FÉLIX: When we talk about humor, we have to differentiate three main forms: comedy, satire and humor. Almost everyone understands more or less what comedy and satire are, genres, on the other hand, almost as old as man. The million dollar question is what humor consists of. PGarcía, pseudonym of José García Martínez-Calín, one of the best writers of “La Codorniz”, perhaps the most important Spanish humor magazine of the 20th century, says that “humorism is the style that, through the trivialization of what is loaded with seriousness manipulative, seeks the spiritual freedom of the recipient through the smile.” It seems like a good definition to me, but since you're asking me about mine, I'll tell you that for me humor, understood as humor, is a method to understand reality and eventually defend ourselves against it. In this sense, it is an attitude towards life, almost a philosophy, a way of looking at and seeing reality, trying to discover in it what is incongruous, absurd, fun, optimistic, with the particularity that the Humor is as much in the one who looks as in the thing looked at. And also a protective shield, a defensive weapon (maybe even a self-help manual). In my case, I think it comes from my reflective personality, but also insecure and doubtful. In the end, one has no choice but to laugh at oneself, and from there, at everything.

PP: Paradox. I very much agree with your arguments, but I disagree with the classification. For me there is no humor without comedy and satire, like irony, parody, etc., are forms within a large umbrella that is humor. Therefore, I invite you to discuss this whole mess “live” when we meet again, okay? Because we don't have space for the topic here. But let's continue. What is the type of humor you like to consume? Is it the same humor that you like to create? I tell you this because, for example, I like to consume good political satire, but I am bad at creating in that modality.

FÉLIX: In general, both as a creator and as a consumer, I like comedy and humor more than satire, because satire is too aggressive for me. But sometimes I also come up with some political satire, I don't know if it's good or bad. In short, I do not disdain at all, but quite the opposite, white humor, humor for humor's sake, which, as you know, for some has a bad press, because they consider it uncommitted. More specifically, I will tell you that I think my humor is very ironic, but not at all sarcastic. I have already told you that I find satire a bit aggressive. What it is is provocative humor, but not offensive, but playful. And crazy. What I am looking for is to provoke my interlocutor to join the game and the madness that I propose. When I find that kind of accomplice, it's wonderful. And then another characteristic of my humor is that it is very verbal. I love word games. When talking about the functions of language (referential, expressive, poetic, appellative...), I always add: “And playful.” Language can be very playful.

PP: Well, for me political humor is used a lot to make satire, but you can make satire with anything. In my annoying opinion, satire is using humor to laugh while criticizing something, but constructively, without offending. Humor that offends, disrespects, attacks, humiliates, even if it is of good artistic elaboration, I consider it to be third category (if it is humor). And I don't see it as satire. Not even as black humor, as some call it. And I am one of those who defends white humor to think and to laugh for the sake of laughing too. For me all types of humor have the same value. And finally, we are twins when it comes to the taste for wordplay. I can't live without them. And now tell me, which comedians do you like the most among the living and deceased and Spanish and foreign? What have been the ones that you think influence your way of creating?

FÉLIX: Phew! It would be an endless list, because in addition, the fields of humor creation are many: literature, cinema, theater, music, graphic humor... But, anyway, here are some names: Los Payasos de la Tele (Gaby, Fofó and Miliki ), Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, Woody Allen, Billy Wilder, Cantinflas, Rafael Azcona, Enrique Jardiel Poncela, Álvaro Cunqueiro, Castelao, Quino, Francisco Ibáñez, Tip y Coll, Gila, Tricicle, Les Luthiers… As a writer, I am not very clear about who has influenced me. What I will tell you is that when I started making humorous cartoons (a field in which I never got fully involved and I regret it), I was very influenced by the black humor of Chumy Chúmez. I even have an anecdote about it that I'm proud of. He and I published almost the same cartoon, but I published it a year before. In mine, a man said to another: “I am poor, but honest.” And the other replied: “Misfortunes never come alone.” Chumy's reproduced almost the same dialogue: “–I am poor, but honest. –I understand. Misfortunes never come alone.” I know it was a mere coincidence – the same thing occurred to both of us, just like that – but I like to joke that the great Chumy plagiarized me.

PP: On one occasion, with my Cuban group “La Seña del humor”, we performed in front of Les Luthiers in Havana in a tribute they gave him. And in the end we got to talking with them at the cocktail party and Marcos Mundstock told me that “that” joke of ours that he saw, they had made it five years ago. I turned red with embarrassment when I realized that he might think we plagiarized them. Marcos realized it and told me. “Don't worry, anyone can think of the same joke. It has happened to us.” I don't know if he did it paternally, but I took it as the teaching of a Master. So if Marcos says it, tell it to the great Chumy Chúmez when you see him in the afterlife, if there is one. Well, I return to the questions: what do you like more, creating humor or analyzing it, reviewing it, “theorizing” it?

FÉLIX: Creating it, although analyzing humor – trying to discover the mechanisms that make us laugh or smile – has its interest and its appeal, and many say – and I am right – that trying to explain humor is anti-humorous. And, of course, reviewing or disseminating it also gives a lot of pleasure.

PP: In my case I agree with you. It gives me pleasure to study humor and I don't find it anti-humorous, far from it. In short, they lose it. And as a creator, do you think it's easier to make people cry than to make people laugh?

FÉLIX: Yes. To make someone cry you just have to step on them, while to make them laugh you have to tickle them. Now seriously: yes, I think that making people cry – that is, making others move to tears – can be easier than making them laugh, although I don't detract from it. I have always distrusted film or literature critics (there are many) who accuse any work capable of touching our heartstrings of being “cheating” and of doing “emotional blackmail,” because many of them truly move us, and that has to be the objective of much of cinema and literature. But it is true that some works do make these types of traps. Indeed, you can make the viewer cry by emotionally blackmailing them, but it is impossible to make them laugh that way. Furthermore, when someone laughs without real desire, when they fake laughter to please their interlocutor, it is very noticeable and is downright painful.

PP: In summary, my opinion: making good art is difficult, whether tragedy or comedy. But making people cry is easier, perhaps because in real life there are much more tragedies and dramas than comedies. Another point: there are techniques, axioms, there is a language to create humor, but not to provoke negative emotions in us. And now a fashionable question: What would be the limits of humor if there were any?

FÉLIX: I am clear that there are, in the same way that, as a journalist, I am clear that the right to information has limits in the right to privacy and honor. The limits of humor are, of course, the Penal Code, and then good taste. You can joke about anything, but not in any way. It is about laughter adding some joy, sweetness or lightness to the misery of the world and not more hatred or suffering. The anti-Jewish joke that we laugh and applaud in the mouth of a Jew will always be reprehensible in the lips of an anti-Semite.

PP: Totally agree. There are external limits, such as the Penal Code that you mention and which would be very severe if it is a dictatorship, or it would be very severe morally, if fanatic minorities rule in social power and internally all of this with our principles manages self-censorship. , it isn't true? But let's change "the vibe." Can you tell any funny, curious or ingenious anecdote that you have experienced related to your work in comedy?

FÉLIX: It's not funny or ingenious, it's just curious: I have always valued clowns a lot and I made my first steps in this sense, many years ago, in a duo format with my friend Héctor Barrera, a Hispanic actor and teacher of actors. Argentinean. We performed under the name Cuarto y Mitad at the Teatro Principal in Pontevedra (Spain) at the Festiclown, the international clown festival that was held for several years in that Galician city. There were performances by professionals and amateurs, and clown workshops taught by internationally relevant figures such as Jango Edwards or Leo Bassi. By the way, we were accompanied on guitar by Xoán Curiel, who today is one of the most important Galician singer-songwriters.

PP: I didn't know that side of you, Félix. Congratulations. You are an all-rounder in humor: you act, write, draw and you are a student and promoter of humor. You can't be more humorous, my friend! Well, on this point, what would you like to do within humor that you haven't done?

FÉLIX: I would like to make graphic humor and publish it continuously. And also stage humor. I would be happy going up to a stage every weekend, no matter how small, and telling “my things.” In both fields I have made my first steps, but nothing more. In literature, perhaps writing and publishing a book of humorous stories. And return to the genre of my first two books, which some called “greguerías”, although they did not reach the ingenuity of Ramón Gómez de la Serna and remained mere verbal jokes. And write comedy: if I had been born thirty years earlier, for theater and cinema; and if he had been born thirty years later, for television and social networks.

PP: I don't think it will be that difficult for you to achieve those goals. You have plenty of talent. And to close, can you think of any questions that you would have liked me to ask you but I didn't? If so, can you answer it now?

FÉLIX: Maybe some geography, so I can show off, because I'm an expert in the subject, but better an elementary level question, so I won't end up making a fool of myself. And now seriously: no, I can't think of any other question for you to ask me, but I do want to ask – for everyone's reflection – one that I ask myself more and more: why do most people systematically call “bad people”? ” to all the jokes based on puns? I say this from my own experience: I have already told you that I love making jokes of this type. It seems to me the opposite: that many of them (and I'm not talking about mine, of course; it would be immodesty) are frankly "good", because they denote notable ingenuity. What do these people mean by “good” jokes?

PP: I can give you my answer (without being sure, of course). For me, making intelligent humor is when the consumer feels intelligent when deciphering the artistic creation that the comedian proposes to make them laugh or smile. An easy, simple joke that everyone understands is therefore not very intelligent humor. For word games (good and bad), the creator has to think, master the language, have a sense of play and humor to weave thoughts, sensations, associations to create them. It's hard to make puns. You have to have your brain “oiled”. Just as it is difficult for consumers to accept them, when they are used to easy, basic, or offensive or vulgar humor. Another thing is the question of taste. For example, I can understand that a joke is very good and not like it for other reasons. But I can't say it's bad. Remember that a joke that is not funny in Tumbuctú, you make it in Remangalatuerca and there they may cry from laughter. And the play on words is a joke. Anyway, I'm sure that white humor is more difficult to do than any other. I've stopped paying attention to those people who despise word games, art for art's sake, laughter for laughter's sake.

And now to finish: could you dedicate a few words to the readers of Humor Sapiens?

FÉLIX: I just congratulate you for the immense privilege you have of being able to enjoy a space dedicated to humor like I don't think there are many in the world.

PP: Millions of thanks for that assessment, millions of thanks for your generosity in accepting this “vis a vis”, millions of thanks for collaborating so much with Humor Sapiens and millions of thanks for existing and knowing you. I say goodbye wishing you good health and many successes.

FÉLIX: Well, I also say goodbye to you and to all the readers of Humor Sapiens. Thank you very much for welcoming me to this wonderful place, where I have been collaborating for more than a year, and for always being so generous and affectionate with me.

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)