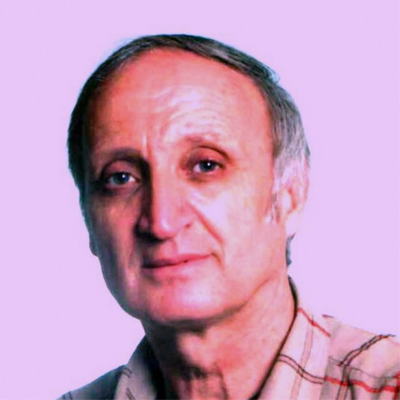

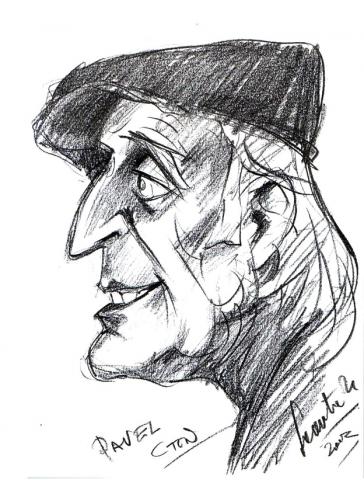

Pregúntense que no ha hecho en esta vida, nuestro invitado de hoy, el rumano Pavel Constantin.

Estudió Bellas Artes durante años, trabajó seis años en aviación (supersónica), jugó fútbol en la División B, Bacau, realizó diez películas de animación, ha ilustrado varios libros, ha participado en exposiciones internacionales de caricaturas y ha publicado en numerosos diarios y revistas del mundo, ha sido miembro de varios jurados en concursos internacionales de humor gráfico, ha publicado dos libros infantiles: Alex & Tudy y Few Weeks and Balloon y sus caricaturas han sido adquiridas por varios museos del mundo, así como por artistas y coleccionistas.

Y, por si fuera poco, ha obtenido premios con sus obras en Japón (varios), Canadá, Italia, China (varios), Rumanía (varios), Austria, Portugal, España (varios), Macedonia, Luxemburgo, Bélgica (varios), Brasil (varios) y Grecia.

Por último, debo decir que también obtuvo premio en nuestro Concurso Internacional Humor Sapiens 2024 y como jurado disfruté mucho su obra.

Por todo lo anterior, es un honor tenerlo hoy aquí en este Vis a Vis.

PP: Bueno, para los seguidores de Humor Sapiens, ¿podrías presentarte? (Quizás mi introducción estuvo incompleta). ¿Cómo te gustaría ser conocido o recordado?

PAVEL: Nací en un pueblo del norte de Rumanía llamado Baluseni. Me ocurre, como a todos, que el lugar de mi infancia me parece el más hermoso del planeta. La libertad total que pasé en la infancia en el pueblo es un pilar fundamental en el desarrollo de la personalidad, de la forma de ver y comprender el mundo. Nunca podré olvidar las aguas donde pescábamos y nos bañábamos, los huertos, con árboles de los que robábamos fruta, ni a los niños con los que jugábamos hasta la medianoche. Sin esta parte de mi vida, creo que mi imaginación habría sufrido una gran discapacidad.

PP: Estimado amigo, ¿en qué momento decidiste dedicarte al humor?

PAVEL: En el instituto, cuando tenía unos 17 años, tuve la suerte de tener un compañero que tenía una colección de revistas de humor en casa. Así vi mis primeras caricaturas. Hasta entonces, me había interesado más el fútbol, sin saber que existían. Mi compañero dibujaba caricaturas, tenía humor, y sus primeras caricaturas aparecieron en un periódico local. Me pareció extraordinario y empecé a dibujar también. Tuve que aprender a caricaturizar la realidad y a la gente. Tuve que aprender una receta para construir la idea de un chiste, y luego me presenté en una redacción, confieso que con menos éxito que mi compañero. Pero este fracaso fue algo bueno. Seguí dibujando mucho y mis dibujos empezaron a publicarse en la prensa. Ese fue el momento en que me contagió esta pasión y todavía no me he recuperado.

PP: Se habrá perdido un buen futbolista, pero ganamos un excelente humorista gráfico. Y lo otro importante es que eres perseverante, por suerte. Y dime, ¿comenzaste a dibujar sin un estilo en particular? Si tuvieras uno, ¿cuál sería? ¿Te influyeron los dibujantes nacionales o extranjeros de aquella época?

PAVEL: Por supuesto que me influyó. En Rumania ya había un pelotón de dibujantes valiosos, artistas valiosos con un humor refinado. Era una verdadera escuela observar cómo dibujaban y cómo reflexionaban sobre las ideas. Tuve una revelación aún mayor al ver dibujos humorísticos de los grandes dibujantes del mundo. Pero creo que todos los dibujantes pasaron por estas etapas.

PP: Por supuesto que sí. Es parte del proceso de formación. ¿Y cómo crees que ha evolucionado tu obra a lo largo del tiempo en términos de forma y contenido?

PAVEL: La caricatura es un fenómeno gráfico muy complejo. Combina medios de expresión de diversas artes: pintura, artes gráficas, poesía, cinematografía o filosofía. La atmósfera, el ángulo de la acción, la luz, etc., son importantes; es decir, una combinación de elementos que enriquecen un mensaje. Solo después de muchos años comprendí esto. Al principio, mi enfoque era muy simplista, casi superficial.

PP: Ese es el aprendizaje que hacen los grandes, porque los mediocres no les interesan las formas. Piensan que si la idea es buena, da igual cómo la expresan y ahí se equivocan. Bueno, continuamos, ¿cuál método prefieres: dibujar caricaturas humorísticas sin texto o con texto? ¿Por qué?

PAVEL: Prefiero hacer caricaturas sin texto. Sin duda, es un enfoque más inteligente que le da valor. Porque así, un dibujo se explica por sí solo, sin palabras. Las palabras te limitan a una sola interpretación. Sin palabras, un dibujo puede tener múltiples significados y interpretaciones.

PP: Estamos de acuerdo total y además, da la posibilidad de que entiendan tu obra en cualquier parte del mundo, porque el dibujo es universal. Y hablando de lenguaje universal, la referencia son los concursos. Dime, entre los muchos premios que has recibido, ¿cuál te conmovió o impactó más?

PAVEL: Hubo algunos premios que marcaron mi evolución porque aumentaron mi confianza en mí mismo. Estuvo el primer premio en Montreal, alrededor de 1982, luego el primer premio en Sintra (Portugal), el premio Hidezo Kondo en Japón, y muchos otros que le siguieron. Los considero una especie de semáforos de referencia en mi trabajo.

PP: Te felicito por todos ellos. Entiendo lo que dices, porque lo que se siente la primera vez que uno obtiene un premio internacional es una emoción muy especial. Y es cierto que te da mucha confianza. Pero me gustaría saber ahora qué tipo de humor disfrutas más crear. Aquí tienes algunas opciones:

a) El que simplemente te hace reír.

b) El que te hace reír y reflexionar.

c) El que te hace pensar, aunque sea solo crítico o satírico.

d) El burlón, irrespetuoso u ofensivo.

¿Y por qué no elegiste los demás? (Si es que dejaste alguno fuera, claro).

PAVEL: El tipo que te hace reír y pensar. Y definitivamente no me gusta el tipo burlón, irrespetuoso u ofensivo. Creo que todos los caricaturistas eligen estas formas de crear y pensar con decencia.

PP: Completamente de acuerdo, amigo mío. Una pregunta de moda: ¿para ti, cuáles son los límites del humor, si los hay?

PAVEL: No creo que el humor tenga límites. Siempre y cuando no traspase la línea de la decencia.

PP: Bueno, la línea de decencia también es un lpimite, ¿no es cierto? Lo que sucede es que es interno. Los otros, los externos, son los que no deben existir, como los que imponen los gobiernos autoritarios, dictaduras de monorías, los dueños de los medios por defender ciertos intereses, etc. Una cosa, ¿alguna vez te han censurado? ¿Te autocensuras a menudo, rara vez o nunca?

PAVEL: Mi país vivió la época del comunismo, y entonces se censuró la libertad de pensamiento. Todos debemos tener cierta autocensura. Censura del sentido común.

PP: Claro que sí, todos tenemos la censura del sentido común como mencionamos, pero como te decía, esa falta de libertad que sufriste (yo también) es la que no debería existir. ¿Y cómo ves el presente y el futuro del humor gráfico?

PAVEL: Estoy seguro de que el humor nacional e internacional tendrá un futuro extraordinario. El potencial del pensamiento humorístico es cada vez más valioso y moderno. Prueba de ello es la gran cantidad de jóvenes y valiosos dibujantes que surgen en todos los continentes.

PP: Eres mucho más optimista que yo. Cuando veo el cierre de tantos espacios para publicar nuestras obras, me aterro, aunque también pienso que es una transición. Cuando se solifique bien el paso a lo digital, con retribuciones monetarias institutidas, volverá a florecer todo, porque mientas haya vida humana, habrá humor. Bueno, y para darle un toque de más ligereza a este Vis a vis, ¿podrías compartir una anécdota divertida, curiosa o ingeniosa que hayas vivido a lo largo de tu carrera en el humor?

PAVEL: No es precisamente anecdótico. Tuve y sigo teniendo problemas con el inglés. En mi país solo había aprendido ruso. Recibí un premio en el gran concurso de Turquía, Aydin Dogan. Había aprendido algunas palabras en inglés del diccionario. En la ceremonia de entrega de premios, vino el gran patrocinador del concurso, Aydin Dogan. También me extendió la mano para saludarme. Mientras se la estrechaba, olvidé todas las palabras que había aprendido. Sin embargo, había memorizado dos palabras mejor, que me apresuré a dirigirle... ¡ADIÓS! No estaba muy orgulloso, pero sonrío al recordarlo.

PP: Ja, ja, claro que es una anécdota y muy graciosa. Gracias por contarla. Y para terminar, ¿hay alguna pregunta que no hice y que te gustaría que hiciera? Si es así, ¿podrías responderla ahora?

PAVEL: Estas preguntas fueron interesantes. Gracias. A veces me pregunto si no habría sido mejor para mí haber sido chef, buceador o ginecólogo.

PP: Puede ser, pero estoy seguro que de igual forma habrías creado chistes sobre comidas, fondos marinos o partos, ja, ja. Y de humorista a humorista, ¿qué consejo me darías?

PAVEL: El mundo está lleno de cosas hermosas. Pero te aconsejo que cultives tu humor a diario. Es beneficioso para el espíritu y la salud.

PP: Aunque estoy seguro que es así como dices, a veces la mente se desvía un poco, pero se domina y todo toma su cauce. Así que te prometo que cumpliré tu consejo. Y por último, ¿quieres dedicarles unas palabras a los lectores de Humor Sapiens?

PAVEL: La revista HUMOR SAPIENS y sus creadores son famosos y reconocidos en todo el mundo. Alimenta tu inteligencia leyendo esta revista. ¡Es una verdadera terapia para el espíritu!

PP: Muchas gracias por tan generosas palabras, querido Pavel. Un honor y una satisfacción que tengas esa opinión de nuestra Humor Sapiens.

También te agradezco de corazón tu tiempo y atención para compartir este vis a vis.

PAVEL: Gracias por su paciencia.

PP: Te deseo mucha salud y éxitos. Un abrazo!!

Interview with Pavel Constantin

by Pepe Pelayo

Ask yourself what our guest today, Romanian Constantin Pavel, hasn't done in this life.

He studied Fine Arts for years, worked in aviation (supersonic) for six years, played soccer in the B Division in Bacau, made ten animated films, illustrated several books, participated in international cartoon exhibitions, and has published in numerous newspapers and magazines around the world. He has served on several juries in international cartoon competitions. He has published two children's books: Alex & Tudy and Few Weeks and Balloon. His cartoons have been acquired by several museums around the world, as well as by artists and collectors.

And, as if that weren't enough, his work has won awards in Japan (various), Canada, Italy, China (various), Romania (various), Austria, Portugal, Spain (various), Macedonia, Luxembourg, Belgium (various), Brazil (various), and Greece. Finally, I must say that you also won an award in our 2024 International Humor Sapiens Competition, and as a judge, I really enjoyed your work.

For all the above reasons, it's an honor to have you here today at this Vis a Vis.

PP: Well, for the Humor Sapiens fans, could you introduce yourself? (Perhaps my introduction was incomplete.) How would you like to be known or remembered?

PAVEL: I was born in a village in northern Romania called Baluseni. It happens to me, as it does to everyone, that my childhood place seems to me the most beautiful place on the planet. The total freedom of childhood spent in the village is a very important building block in the development of personality, of the ways of looking at and understanding the world. I can never forget the waters in which we caught fish and bathed, the vegetable gardens, with trees from which we stole fruit or children with whom we played until midnight. Without this part of my life, I think my imagination would have suffered from a great disability.

PP: Dear friend, when did you decide to dedicate yourself to humor?

PAVEL: In high school, when I was about 17 years old, I was lucky to have a classmate who had a collection of humor magazines at home. That's how I saw my first cartoons. Until then, I had been more concerned with football, not knowing that cartoons existed in the world. My classmate drew cartoons, had humor, and his first cartoons appeared in a local newspaper. I thought it was extraordinary and I started drawing too. I had to learn to caricature reality and people. I had to learn a certain recipe for building the idea of a joke, then I showed up at an editorial office, I confess with less success than my classmate. But this failure was a good thing. I continued to draw a lot and my drawings started to be published in the press. That was the moment when I was infected with this passion and I still haven't recovered today

PP: We may have lost a good footballer, but we gained an excellent cartoonist. And the other important thing is that you're persistent, luckily. And tell me, did you start drawing without a particular style? If you had one, what would it be?

Were you influenced by the national or international cartoonists of that era?

PAVEL: Of course I was influenced. In Romania there was even then a platoon of valuable cartoonists, valuable artists with a refined humor. It was a real school to watch them how they draw and how they think about ideas. I had an even greater revelation when I saw humorous drawings by the world's great cartoonists. But I think all cartoonists went through these stages

PP: Of course. It's part of the training process. And how do you think your work has evolved over time in terms of form and content?

PAVEL: Caricature is a very complex graphic phenomenon. It combines means of expression from several arts. From painting, graphics, poetry, cinematography or philosophy. The atmosphere, the angle of an action, light, etc. are important. that is, an interweaving of elements for the benefit of a message. Only after many years did I understand this. At first I had a very simplistic, almost superficial approach.

PP: That's what great artists learn, because mediocre artists aren't interested in form. They think that if the idea is good, it doesn't matter how they express it, and that's where they're wrong. So, moving on, which method do you prefer: drawing humorous cartoons without text or with text? Why?

PAVEL: I prefer to make cartoons without text. It is definitely a more intelligent approach, which gives value to a cartoon. Because this way a drawing explains itself, without words. Words limit you to one interpretation. Without words a drawing can have multiple meanings and understandings.

PP: We completely agree, and it also makes it possible for your work to be understood anywhere in the world, because drawing is universal. And speaking of a universal language, competitions are the reference. Tell me, among the many awards you've received, which one moved or impacted you the most?

PAVEL: There were a few awards that marked my evolution because they increased my confidence in myself. There was the first prize in Montreal, around 1982, then the first prize in Sintra (Portugal), the Hidezo Kondo award in Japan, but also many others that followed. I consider them a kind of reference traffic lights in my work.

PP: Congratulations on all of them. I understand what you're saying, because the first time you win an international award, it's a very special feeling. And it's true that it gives you a lot of confidence. But I'd like to know what kind of humor you enjoy creating the most. Here are some options:

a) The kind that simply makes you laugh.

b) The kind that makes you laugh and reflect.

c) The kind that makes you think, even if it's just critical or satirical.

d) The kind that's mocking, disrespectful, or offensive.

And why didn't you choose the others? (If you left any out, of course.)

PAVEL: The kind that makes you laugh and think. And I definitely don't like the mocking, disrespectful or offensive kind. I think all cartoonists choose these ways to create and think decently.

PP: I completely agree, my friend. A hot question: For you, what are the limits of humor, if any?

PAVEL: I don't think humor has limits. As long as it doesn't cross the line of decency.

PP: Well, the line of decency is also a limit, isn't it? It's just that it's internal. The others, the external ones, are those that shouldn't exist, like those imposed by authoritarian governments, minority dictatorships, media owners defending certain interests, etc. One thing, have you ever been censored? Do you self-censor often, rarely, or never?

PAVEL: My country experienced the times of communism, then freedom of thought was censored. We all have to have a certain self-censorship. Censorship of common sense.

PP: Of course, we all have the censorship of common sense, as we mentioned, but as I was saying, the lack of freedom you suffered (and I did too) is something that shouldn't exist. And how do you see the present and future of graphic humor?

PAVEL: I am sure that national and international humor will have an extraordinary future. The potential of humorous thought is increasingly valuable and modern. Proof of this is the large number of young and valuable cartoonists appearing on all continents.

PP: You're much more optimistic than I am. When I see the closure of so many spaces for publishing our work, I'm terrified, although I also think it's a transition. When the shift to digital is properly solidified, with established monetary compensation, everything will flourish again, because as long as there's human life, there will be humor. Well, to add a touch of lightness to this Vis a Vis, could you share a funny, curious, or witty anecdote you've experienced throughout your career in comedy?

PAVEL: It's not exactly anecdotal. I had and still have problems with English. In my country I had only learned Russian. I received a prize at the great competition in Turkey Aydin Dogan. I had learned a few English words from the dictionary. At the award ceremony, the great patron of the competition, Aydin Dogan, came. He also extended his hand to greet me. While I was shaking his hand, I forgot all the words I had learned. I had memorized two words better, however, which I hurried to address to him... GOOD BY! I was not very proud, but I smile when I remember.

PP: Ha ha, of course it's a funny story. Thanks for sharing it. And finally, is there a question I didn't ask that you'd like me to ask? If so, could you answer it now?

PAVEL: Those were interesting questions. Thank you. I sometimes wonder if it wouldn't have been better for me to have been a chef, a diver, or a gynecologist in my life.

PP: Puede ser, pero estoy seguro que de igual forma habrías creado chistes sobre comidas, fondos marinos o partos, ja, ja. Y de humorista a humorista, ¿qué consejo me darías?

PAVEL: The world is full of beautiful things. But I advise you to cultivate your humor daily. It is beneficial for the spirit and health.

PP: Although I'm sure it's exactly what you say, sometimes the mind wanders a little, but it's controlled and everything falls into place. So I promise I'll follow your advice. And finally, would you like to say a few words to the readers of Humor Sapiens?

PAVEL: The magazine HUMOR SAPIENS and its creators are famous and well-known in the world. Feed your intelligence by reading this magazine. It is a true therapy for the spirit!

PP: Thank you so much for your kind words, dear Pavel. It's an honor and a pleasure that you have that opinion of our Humor Sapiens.

I also sincerely thank you for your time and attention in sharing this visit.

PAVEL: Thank you for your patience.

PP: I wish you good health and success. Hugs!

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)