Los surrealistas, encabezados por André Breton, acuñaron el concepto de “humor negro” en 1939. Debía ser aquél que se opusiera al humor evasivo, complaciente y conformista, debía atacar los convencionalismos sociales y los falsos valores establecidos, y tratando de modo atípico temas trascendentales como la muerte, el amor o la moral despojándolos de sus contenidos tópicos y retóricos, obligar al lector a la búsqueda de una respuesta personal.

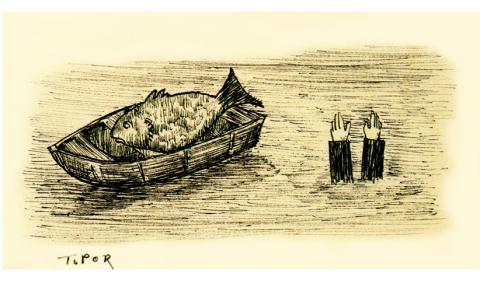

Si lo más característico del humor negro es la mezcla de lo ingenuo con un trasfondo próximo a lo macabro, no cabe duda que Roland Topor (París, 7 de enero de 1938-16 de abril de 1997), es uno de

los máximos representantes en el continente europeo.

Topor fue ilustrador, dibujante, escritor, pintor y cineasta francés, rompió moldes y ha trascendido el tiempo. Bien vale recordarlo en el próximo 88 aniversario de su nacimiento.

Hijo del pintor polaco nacionalizado francés Abram Topor (Varsovia, 1903-París, 1992) -formado en la Academia de Bellas Artes de Varsovia-, Roland Topor heredó de su padre el talento por el dibujo y la pintura, los retratos y las caricaturas, así como el gusto por lo grotesco. Pasó sus primeros años en París, en la rue Corbeau (hoy rue Jacques-Louvel-Tessier) del 10.º distrito; luego en Saboya, donde junto a sus padres, inmigrantes judíos polacos, se ocultaron durante la ocupación nazi.

Estudió en la Escuela de Bellas Artes de París, colaboró en el periódico Hara-Kiri y compartió su sentido del humor negro , ácido y cínico, pero también una vena más rosa, en la revista Elle. Fue uno de los creadores en 1962 del Grupo Pánico, con Fernando Arrabal, Olivier O. Olivier, Alejandro Jodorowsky y Jacques Sternberg.

Fue en 1997, año en que Topor fallecía a los 59 años, que gracias a una publicación de La Academia del Humor, que dirigía P. García, y a la editorial Anagrama tuve en mis manos los ejemplares de “Los alimentos espirituales”, y “Acostarse con la reina”, donde pude disfrutar por primera vez de sus narraciones, una colección de pequeños horrores cotidianos que, de la mano de Topor, se convierten en realidades monstruosas que se burlan de los lectores.

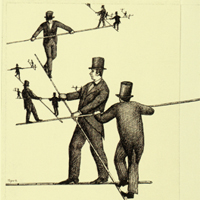

Entonces quise profundizar sobre sus caricaturas, que me impresionaron emocionalmente y se caracterizan por una combinación muy particular de crueldad, absurdo y lucidez crítica. Para estudiosos de sus dibujos, algunos rasgos claves son los siguientes:

Humor negro radical

La risa surge de lo macabro, lo cruel o lo moralmente incómodo.

La violencia, la muerte, la humillación y el sufrimiento aparecen tratados con ironía fría, casi indiferente.

Surrealismo cotidiano

No recurre tanto a paisajes oníricos complejos, sino a situaciones simples llevadas a una lógica absurda.

Lo inquietante nace de pequeñas alteraciones en lo normal: un cuerpo, un gesto o una relación humana.

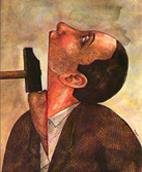

Crítica feroz al poder y a la sociedad

Ataca instituciones como la autoridad, la familia, la medicina, la justicia o la moral burguesa.

El ser humano aparece como víctima y verdugo al mismo tiempo.

Estilo gráfico aparentemente simple

Dibujo limpio, líneas claras, casi ingenuas.

Esta sencillez contrasta con la brutalidad del contenido, aumentando el impacto psicológico.

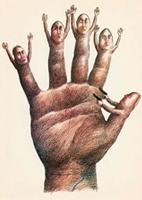

Deshumanización del cuerpo

Cuerpos mutilados, fusionados, explotados o usados como objetos.

El cuerpo es un campo de batalla simbólico donde se revela la violencia social y mental.

Pesimismo lúcido

No hay moraleja consoladora.

Sus imágenes sugieren que el absurdo y la crueldad no son excepciones, sino partes estructurales de la condición humana.

Espíritu del Movimiento Pánico

Como miembro del Mouvement Panique (con Arrabal y Jodorowsky), su obra celebra el caos, la provocación y el rechazo a la razón ordenadora.

En conjunto, las caricaturas de Topor no buscan agradar, sino incomodar, perturbar y obligar a pensar, usando el humor como un bisturí más que como un alivio.

Tribute to the French Artist Roland Topor

By Francisco Puñal Suárez

The Surrealists, led by André Breton, coined the concept of “black humor” in 1939. It was meant to oppose escapist, complacent, and conformist humor; it was intended to attack social conventions and false established values and, by treating transcendental themes such as death, love, or morality in an atypical way—stripped of their topical and rhetorical content—to force the reader to search for a personal response.

If the most characteristic feature of black humor is the combination of naïveté with an undertone close to the macabre, there is no doubt that Roland Topor (Paris, January 7, 1938 – April 16, 1997) is one of its foremost representatives on the European continent.

Topor was a French illustrator, draftsman, writer, painter, and filmmaker. He broke molds and transcended time. It is well worth remembering him on the upcoming 88th anniversary of his birth.

The son of the Polish painter naturalized as French Abram Topor (Warsaw, 1903 – Paris, 1992)—trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw—Roland Topor inherited from his father a talent for drawing and painting, portraiture and caricature, as well as a taste for the grotesque. He spent his early years in Paris, on rue Corbeau (today rue Jacques-Louvel-Tessier) in the 10th arrondissement; later in Savoy, where, together with his parents—Polish Jewish immigrants—he went into hiding during the Nazi occupation.

He studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, collaborated with the newspaper Hara-Kiri, and shared his sense of black, acid, and cynical humor—though also a softer, more “pink” vein—in Elle magazine. In 1962, he was one of the founders of the Panic Group, together with Fernando Arrabal, Olivier O. Olivier, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Jacques Sternberg.

It was in 1997, the year Topor died at the age of 59, that—thanks to a publication by the Academy of Humor, directed by P. García, and to Anagrama Publishing—I first held in my hands copies of Spiritual Nourishments and Sleeping with the Queen, where I was able to enjoy his narratives for the first time: a collection of small everyday horrors that, under Topor’s hand, become monstrous realities that mock the reader.

I then wanted to delve deeper into his caricatures, which impressed me emotionally and are characterized by a very particular combination of cruelty, absurdity, and critical lucidity. For scholars of his drawings, some key features are the following:

Radical Black Humor

Laughter arises from the macabre, the cruel, or the morally uncomfortable.

Violence, death, humiliation, and suffering are treated with cold, almost indifferent irony.

Everyday Surrealism

He does not so much resort to complex dreamlike landscapes as to simple situations carried to an absurd logic.

The disturbing emerges from small alterations of the normal: a body, a gesture, or a human relationship.

Ferocious Critique of Power and Society

He attacks institutions such as authority, the family, medicine, justice, or bourgeois morality.

Human beings appear simultaneously as victims and executioners.

Apparently Simple Graphic Style

Clean drawing, clear lines, almost naïve.

This simplicity contrasts with the brutality of the content, increasing the psychological impact.

Dehumanization of the Body

Bodies are mutilated, fused, exploded, or used as objects.

The body becomes a symbolic battlefield where social and mental violence is revealed.

Lucid Pessimism

There is no comforting moral lesson.

His images suggest that absurdity and cruelty are not exceptions but structural parts of the human condition.

Spirit of the Panic Movement

As a member of the Mouvement Panique (with Arrabal and Jodorowsky), his work celebrates chaos, provocation, and the rejection of ordering reason.

Taken as a whole, Topor’s caricatures do not seek to please, but to unsettle, disturb, and force thought, using humor as a scalpel rather than as relief.

(This text has been translated into English by ChatGPT)