“Nuestra esperanza de que la técnica del chiste no podía por menos de revelarnos la íntima esencia del mismo nos mueve, ente todo, a investigar la existencia de otros chistes de formación semejante a la del anteriormente examinado. En realidad, no existen muchos chistes de este tipo, mas si lo suficientes para formar un pequeño grupo caracterizado por la formación de una palabra mixta”. (1)

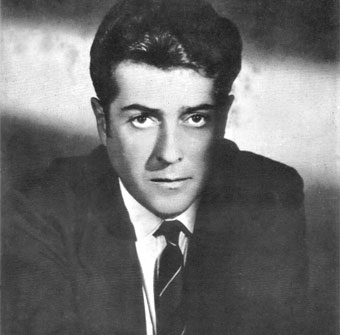

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

Una de las piedras basales del humor español del Siglo XX es la prolífera obra del genial Álvaro de Laiglesia González, que empleó varios seudónimos: “Peribáñez”, “El Condestable Azul” y “Alcaponen”. (1922-1981).

Hoy, al leerlo nuevamente, después de tantas décadas pasadas sumando a otros extraordinarios exponentes, es acceder a un magnífico mundo creativo con pocos parangones.

Hay quienes les puede caber haberlo hecho hace tiempo, por lo que en estos aciagos tiempos, al adentrarse serán capaces, a pesar de todo, de reír levantando la vista hacia un horizonte difuso o, muchas veces, sombrío.

En lo personal, hace muchos años de Laiglesia nos acompañó con fruición en nuestros primeros libros atesorados y a comenzar a reflexionar sobre la capacidad humana de reírse.

Es humor literario por excelencia, tan distinto al slapstick ingenuo (humor con caídas y tropiezos).

La ancestral pregunta ¿qué es el humor? continúa sin una única respuesta, pero en el Siglo XXI hemos avanzado bastante al respecto pues ahora sabemos indudablemente que falta mucho para satisfacer el dilema; conocer la vida y obra de los humoristas es un buen camino al efecto, aunque sea muy extenso y lleno de divertidas sorpresas.

|

“A lo mejor, la lección fundamental que nos deja el espejo realista no es la de calcar la realidad y producir un documento, sino partir de lo real para seguir mucho más allá, agudizando los perfiles a sabiendas de que el realismo puro es imposible. Como apuntaba el narrador de Cerca de la ciudad, hay que ʽvolver a inventar una vez más el neorrealismoʼ (Benet, 2012: 267); llegar a sus mismos objetivos pero abriendo el abanico de posibilidades, conjugando la verdad y la revelación, admitiendo más de una realidad al mirar desde más ángulos, crispados, afilados y sin embargo (o tal vez por eso) cómicos”. Manuela Rodríguez de Partearroyo Grande. Los Ojos de la Máscara. Poéticas del grotesco en el Siglo XX: neorrealismos, expresionismos y nuevas miradas. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Programa de Estudios Literarios de la Facultad de Filología. Página 317. Madrid, España. 2015. |

UNA VUELTA DE TUERCA

El destacado dibujante humorístico español Pablo San José García (1926-1998) expresó en una entrevista: “Todo el humor de nuestra picaresca, ácido y tenebroso, ¿no reflejaba la realidad más palpitante de su tiempo? Entre nosotros el humor bondadoso, y no digamos el poético, no tiene nada que hacer en cuanto al consumo general. Si no va contra algo o contra alguien, el auditorio, decepcionado, comenta: ʻ¡Qué tontería!ʼ, o ʻ¡Vaya gansada!”. (2)

A la manera del eximio exponente del renacimiento, (siglos XV y XVI), Nicolás Maquiavelo (1469-1527), más citado que leído, que en 1513 escribió su ensayo con consejos al Príncipe, el multifacético humorista español Álvaro de Laiglesia, (3) realizó otro tanto para un futuro monarca y desde luego para todos sus contemporáneos entusiastas de su obra.

“Alteza:

Procurad no tener fama de gracioso. En la vida se puede tener fama de cualquier cosa; pero de gracioso, nunca. Me diréis: ʻ¿Se puede tener fama de cepillo?ʼ Y yo os responderé: Parece absurdo, pero no hay inconveniente en tener fama de cepillo. Pero de gracioso, insisto, sí. Es peligrosísimo, no sólo en vuestra elevada esfera social, sino en todas. Yo tuve un amigo que tenía fama de gracioso y murió de hambre por eso mismo. Era un señor sano y robusto, os lo aseguro, que masticaba sin el menor esfuerzo los granillos de las uvas. Era un hombre feliz, puedo jurarlo si lo creéis necesario. Pues bien: una sola vez contó un chiste de mucha risa, y la gente empezó a decir que era muy gracioso. (…)

¿Se da cuenta Vuestra Alteza de lo peligroso que resulta tener fama de gracioso? (…)

¿Comprende ahora Vuestra Alteza por qué jamás debe adquirir fama de gracioso? Por mi parte, ya estáis prevenidos. Y ya sabéis que príncipe prevenido, vale por dos”. (4)

TAMBIÉN

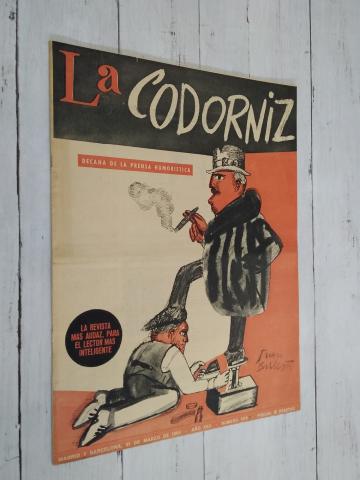

Tal lo sintetizado por Félix Cepriá (Tebeosfera, 2008): “Álvaro de Laiglesia González Labarga, fue escritor y director de la revista satírica española ʽLa Codornizʼ 1941 a 1978, imprimiéndole su destacada inventiva a “La revista más audaz para el lector más inteligente”, que existió incluyendo la punitoria censura: 1973 y 1975, por Manuel Fraga Iribarne (1922-2012). La norma fue recién modificada por el Real Decreto-Ley 24/1977.

Comenzó a escribir con humor a los 14 años de edad en “Unidad” y en “Fotos”; luego llegó a ser el subdirector de la publicación infantil “Flecha” (Barcelona, 1937 y 1938). Trabajó intensamente hasta su inesperado fallecimiento.

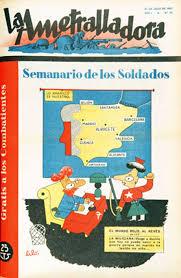

Un año después, ya como autor a tiempo completo se desempeñó como Redactor en Jefe en el semanario “La Ametralladora” (1937-1941), 100.000 ejemplares durante la Guerra Civil Española, fundado por el excelente humorista y dramaturgo Miguel Mihura Santos (1905-1977).

En Cuba trabajó unos meses en “Diario de la Marina”, antes que lo hiciera Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (1926-2016) en su juventud, sin imaginar las décadas posteriores, que continúa, la vigencia por la fuerza de las armas del gobierno autocrático sustentado en empleados públicos militarizados, una vez derrocado el nefasto dictador sargento Rubén Zaldívar que, a partir de 1939, se llamó Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar.

Luego, por un breve tiempo, trabajó en el vespertino “Informaciones” (1922-1983) a propuesta de su Director Víctor de la Serna y Espina (1896-1958). Editó 90.000 ejemplares; fue cambiando su línea editorial.

Fue un autor notablemente prolífero y disruptivo en muchos aspectos. Su dominio del idioma es muy destacable, sin caer nunca en los insondables laberintos de la banalidad de la falsa o innecesaria erudición.

Nunca buscó el degradante beneplácito obsecuente ni lo políticamente correcto de los políticos incorrectos. Probablemente, si viviera en la actualidad revisaría algunas expresiones y decisiones personales, pero aquí recodamos sin juzgar que ya es mucho.

Su divisa podría haber sido: Humor, sin ofender ni agraviar.

Todos sus libros fueron exitosos, muchos superando las diez ediciones en Planeta, Barcelona. Por caso “Tocata ja”, en el primer trimestre logró cinco de 3.300 ejemplares cada una (cuatro en octubre y una en diciembre).

Sus títulos son humorísticos, superando las 200 páginas cada uno; principalmente reunieron artículos publicados; a veces son historias de sus entrañables personajes como “Mapi” que integran una serie de cuatro libros.

Según la fuente consultada la cantidad total varía pero en todos los casos superan los treinta.

“Un náufrago en la sopa” (1944), “Todos los ombligos son redondos” (1956), “El baúl de los cadáveres” (1948), “La gallina de los huevos de plomo” (1950), “Se prohíbe llorar” (1953), “Sólo se mueren los tontos” (1954), “Dios le ampare, imbécil” (1955), “Más allá de tus narices” (1958), “¡Qué bien huelen las señoras!” (1958), “En el cielo no hay almejas” (1959), “Te quiero, bestia” (1960), “Una pierna de repuesto” (1960), “Los pecados provinciales” (1961), “Tú también naciste desnudito” (1961), “Tachado por la censura” (1962), “Yo soy Fulana de Tal” (1963), “Libertad de risa” (1963), “Mundo, Demonio y Pescado” (1964), “Con amor y sin vergüenza” (1964), “Fulanita y sus menganos” (1965), “Racionales, pero animales” (1966), “Concierto en Sí amor” (1967), “Cada Juan tiene su Don” (1967), “El baúl de los cadáveres” (1967), “Los que se fueron a la porra” (1957), “Se busca rey en buen estado” (1968), Cuéntaselo a tu tía” (1969), “Nene, caca” (1969), “Réquiem por una furcia” (1970), “Mejorando lo presente” (1971), “Medio muerto nada más” (1971), “El sexy Mandamiento” (1971), “Tocata en ja” (1972), “Listo el que lo lea” (1973), “Libertad de risa” (1973), “Es usted un mamífero” (1974), “Réquiem por una furcia” (1974), “Una larga y cálida meada (1975), “Cuatro patas para un sueño” (1975), “El sobrino de Dios” (1976), “Tierra cachonda” (1977), “Se levanta la tapa de los sexos” (1978), “Más allá de tus narices”, (1978) “Los hijos de Pu” (1979), “Morir con las medias puestas” (1980), “Mamá, teta” (1981), “Todos los ombligos son redondos” (1982).

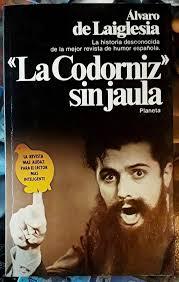

En su póstuma creación “La Codorniz sin jaula” (1981) su hija Beatriz apuntó en Prólogo post mortem: “Mi padre era elegante, desprendido, guapo, y de buena familia, y supo aprovechar al máximo esa distancia hacia lo cotidiano que impone la buena educación. Tengo para mí que, gracias a todo eso, y a su talento, a su capacidad de trabajo, a su falta de pereza, a Fernando Perdiguero y quizá un poco a su sentido del humor, pudo sacar a la calle La Codorniz durante treinta y tantos años. Lo hizo sin tomarse demasiado a pecho la lucha diaria contra la censura, pero sobre todo la lucha contra aquellos infinitos matices del gris que impregnaban el ambiente”.

Todos los tomos publicados por Planeta están engalanados con geniales sobrecubiertas a todo color del prolífero y multipremiado dramaturgo, humorista gráfico y periodista, primer marqués de Daroca Ángel Antonio Mingote Barrachina (1919-2012), miembro pleno de la Real Academia Española, doctor honoris causa por la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares y por la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, más conocido como Mingote lo que encierra sí mismo una humorada.

En varias oportunidades, también colaboró exitosamente con textos que fueron emitidos por la Televisión Española.

SU PENSAMIENTO SOBRE EL HUMOR

A nuestro entender, es poco conocida aún por especialistas, la inteligente entrevista de Pedro Rodríguez al autor y directivo periodístico que aquí nos ocupa, donde detalla su perspectiva con respecto al humor como a su ejercicio, sumando su perspectiva de varias otras cuestiones: guerra, divorcio, política, libertad, noticias falsas, respeto y valorización de la diversidad humana, la Academia, etcétera. Reflejan su época que, muy probablemente, hoy en día varios aspectos habrían variado o los hubiera mantenido en su fuero íntimo.

Es un documento de real valía que agrega valor a la bibliografía atinente y a la comprensión del fenómeno de “La Codorniz” mediante el periodismo gráfico impreso durante tres extensas décadas.

“A MODO DE EPÍLOGO: Álvaro de Laiglesia, en serio

BONJOUR, TRISTESS…

Lo primero que verá usted será el lápiz rojo, al alcance de la mano, sobre la mesa desnuda.

Por lo demás, permítaseme decirles que son ustedes unos ingenuos: nadie se ríe en Claudio Coello, 46, cuarto a la derecha, ni hay cascabeles, ni una voz fuera de su sitio. A lo mejor tiene que ser así: el suelo, viejo y crujiente; la luz escasa; los sillones, negros; los visillos, inmaculados; el timbre, como el de los juzgados. Al otro lado de la de los visillos, hay señores encorvados sobre tableros, como en el saloncito de una pensión de primera, todo confort, trato hogareño. Como un viejo laboratorio de sangres. Por cierto, ¿cómo está usted, señor De Laiglesia? (5)

-Muy bien, gracias. Muy satisfecho de ser el director más antiguo de Madrid. Llevo más de veintiocho años dirigiendo el mismo periódico, y soy el decano. Batir marcas siempre es divertido.

Luego, te cuenta lo del tocólogo aquel de treinta años que se tenía el pelo de blanco y se hacía el reumático para que las señoras se denudaran sin complejos. Pero no nos vamos a reír ni una sola vez. A lo mejor, tiene que ser así: sin un sola codorniz en el despacho de frailuno; con todos los libros detrás, alineados como señoras gordas con faja; con su insufrible voz caliente; luchando por dejar de Cela, Dalí; pidiendo con la mirada que no le pida ʽboutadesʼ (comentario ingenioso), como las baronesas a la hora de los postres; este sagrado niño viejo que lleva veintiocho años enseñando el Corán al viejo y sagrado país… Por cierto: ¿de qué presume ahora señor De Laiglesia?

Ya se lo he dicho. Presumo de ser el Decano. Por lo demás, estoy contento de la vida. Estoy empezando mi libro número treinta y cinco, tengo todas mis ideas intactas, y calculo llegar a los sesenta o setenta libros. No creo en el escritor de una obrita. Creo que, para quedar, el escritor ha de ser más caudaloso, como Victor Hugo, Balzac o Shakespeare.

-Pero las comparaciones son odiosas, ¿verdad?

-Efectivamente. Ellos eran mucho más viejos que yo.

Naturalmente, ha avisado que no nos moleste nadie…

TACHADO POR LA CENSURA

-¿Quién está detrás de La Codorniz, Álvaro?

-Por el hecho de ser humorista, uno ha de ser independiente. Mi empresa nunca me ha atizado ni presionado. Un humorista no puede ser monárquico, ni republicano, ni falangista. Uno ha de estar por encima de todo, en una nube rosada, jamás tormentosa, observando lo que ocurre. La prueba de esa independencia es que la revista sigue en pleno vigor y que su director no ha cambiado. Han cambiado los directores de los periódicos, han cambiado los ministros, y yo podía haber caído con un grupo. Pero no ha sido así.

-¿Cuál fue el peor trago, Álvaro?

-Los mayores problemas fueron siempre técnicos. (…) Pegas de otro tipo, también son de aquella época: cuando los censores me tachaban la palabra hígado, porque decían que era de mal gusto; cuando me echaron abajo una foto de un indio diciéndome ʽque se parecía a Jesucristo. Pero yo no presumido de eso. En el país ha habido siempre una corriente de bulos sobre La Codorniz que nunca quise desmentir porque era una publicidad muy eficaz. A La Codorniz le atribuyen portadas y chistes que jamás publicó ni quiso publicar. Aquello de ʽEl cojín es a una equis, como…ʼ. Ciertos partes meteorológicos, ciertos chistes chocarreros, lo del huevo de Colón, y otras muchas cosas llenas de ingenuidad y estupidez… De todas formas, yo calculo que en veintiocho años, habré tenido medio centenar de multas. Y en esos últimos tiempo, nada importante.

-¿Lo de los Ministerios suscritos, me lo creo?

- Sí. Créaselo. O, por lo menos, que leen la revista. Por algo es la más audaz, para el lector más inteligente. Parece lógico que la lean los políticos. Pero ni en caso que hubiera las mayores libertades, yo convertiría la revista en revista politizada. El humor está por encima de la política.

-Pero eso es curioso. ¿Por qué todos los periódicos hemos politizado a los humoristas?

-Allá los periódicos. Allá las exigencias de la prensa diaria. Para ser un buen humorista, uno ha de ser un poco de todo. Yo soy un poco falangista porque, efectivamente, creo en una España faldicorta y alegre. Soy un poco comunista, porque me parece monstruoso que los derechos de los grandes escritores prescriban a los cincuenta años de su muerte y, en cambio, las fincas se hereden por los siglos de los siglos. Soy un poco monárquico, porque me gustan las buenas maneras y besar la mano a las señoras. Soy un poco republicano, porque es muy simpático que los tenderos puedan llegar a ministros. Soy un poco demócrata, porque me divierte que los problemas se puedan resolver con votaciones…O sea, que el humorista tiene que tomar esos poquitos, lo mejor de cada sistema. Ahora, La Codorniz es la única revista de humor ʽpuroʼ de Europa. En Italia se hizo puro con Mussolini, porque no se podía hacer humor político.

-¿Qué fue lo más gordo que publicó, Álvaro?

-Hombre; lo más gordo, no sé. El mayor disgusto me lo dio aquella parodia que hicimos de Arriba. Ahora no hubiera pasado nada; pero, en aquella época, había temas intocables. De verdad que el país ha evolucionado mucho. De cualquier forma, el miedo al humor de La Codorniz que hubo en aquellos años, me pareció siempre excesivo. Yo hubiera llegado, con mi equipo, un poco más lejos, si no hubiera habido una Cesura que nos lo impedía. El humor no puede hacer daño. Hay que tomarlo como un bálsamo que cura, y no como un abrasivo. En Francia, En Inglaterra, en Alemania, no hay límites para el humor; porque saben que el humor no derriba regímenes ni maleduca al pueblo.

-En conjunto, ¿los censores se les dan mejor que las señoras?

-Los censores no se le dan bien a nadie. Tenemos que hacernos más tolerantes en este país. Yo recuerdo, estando en Copenhague, que iba paseando frente al Palacio Real. Y de pronto, salió del palacio un coche en el que iba el rey Federico IX, que se dirigía a la ciudad a hacer compras. A comprarse calcetines o crema de afeitar. Bueno, pues muy bien. Y, en cambio, recuerdo que fui a Málaga a pasar una Semana Santa, y estaba la carretera llena de policías porque se movía un ministro. Estos pequeños endiosamientos no son normales a nivel europeo. Tenemos que irnos acostumbrarnos a considerar a los políticos como unos funcionarios, más o menos bien pagos, que se ocupan, más o menos bien, de administrar nuestros intereses. Pero aquí aún seguimos gritando: ʽYo soy don Fulano de Talʼ... De verdad que tenemos que aprender a reírnos de nosotros mismo.

LOS QUE SE FUERON A LA PORRA

-¿Usted no ha notado, Álvaro, que el país parece que tiene menos ganas de reírse?

-Si no las tiene, debe sacárselas de alguna parte. Porque problemas los tienen en todos los países. Serán más ricos que nosotros, pero tienen buenos problemas. Los que tenemos que ir haciendo aquí es organizar la oposición. Yo creo que la gran solución del país, es la creación del partido ʽOposʼ.

-¿El qué…?

-El ʽOposʼ, apócope de ʽOposiciónʼ. No, no es ningún chiste. En Inglaterra tienen organizada su Oposición, de tal manera que un partido está en Poder, y el resto en el ʽOposʼ. Yo digo que aquí hay unos cuantos españoles en el Poder, y el resto está en el Querer. Bueno. Con el ʽOposʼ cabría el contraste de pareceres. Parte del país sería ʽOposʼ, y sería la manera de establecer un diálogo. Para jugar al frontón hay que tener una pared, porque si no los pelotazos, como ocurre ahora, se pierden en el mar. El ʽOposʼ sería un sistema de sístole y diástole para establecer el equilibrio. O sea que sería la pared del sistema. Y los señores en el Poder, al cesar, pasarían al ʽOposʼ. Y así… Y conste que le llamo ʽOposʼ porque ʽOposiciónʼ es tan largo…

-Bueno, bien. Pero el español, Álvaro, ¿no sigue siendo bajito y con muy mala uva?

-Es que la vida en los países que todavía son pobres, y para comprender al nuestro basta verlo desde el aires prescindiendo del cinturón costero, es más dura. Nuestros problemas han sido de pedazo de pan hasta no hace mucho. Otros países tienen problemas de televisor y así tienen el humor más suave. Pero yo no creo que el español sea bajito y con mala leche de por sí, sino por las condiciones de vida que ha tenido. Además, la generación actual toma mucha leche y muchas vitaminas.

-¿El país ha pagado los servicios prestados a los humoristas?

-Al humorista no se le debe nada. Yo no aspiro a tener ʽmensajeʼ. Yo me limito a contar lo que veo. No somos apóstoles de nadie, ni devotos de nadie. No hacemos daño. Yo no opero los tumores de la sociedad: les pongo, simplemente, un calmante. Ni siquiera en una determinada época fuimos los que podíamos criticar al sistema. Criticábamos a la vida. Ahora me dicen que en la Universidad se lee menos La Codorniz.

-¿Rusia siendo culpable, Álvaro?

-Culpables somos todos. ¿Cuántos movimientos que combatieron contra esto y contra lo otro, están ahora al lado de esto y de lo otro? Ni Rusia es culpable, ni Estados Unidos son culpables. Usted y yo somos tan culpables como Mao, porque entre todos hemos creado un mundo en el que han podido proliferar tipos peligrosos.

-¿Peo no se ha arrepentido de haber estado en la División Azul?

-Bueno; ya lo he explicado aluna vez que fui a Rusia porque estaba enamorado de una mujer eslava. También, porque aquella era una gran aventura europea para un muchacho de 18 años. Pero yo, fundamentalmente, fui porque quise ver a una persona que estaba ceca de allí, pero no la encontré.

-¿No ha pasado factura?

-No, en absoluto. Ni siquiera me he puesto las medallas que gané.

-Al final, los de su generación, ¿se fueron a la porra políticamente?

-Verdaderamente, no tenemos muchas cosas de las que podemos presumir. Pero es que los ideales andan por todo el mundo de capa caída. Me gustaba José Antonio por lo que decía de las ʽcostras inútilesʼ que habrían de caer. Puede que a esta civilización la salve no una edificación nueva, sino la que se consiga construir con los cascotes que hemos ido dejando en el campo de batalla. Una piedra aquí, otra reliquia allí, un recuerdo de un sistema nuevo. De todas formas, la verdad es que yo no participé en las inquietudes políticas de mi generación. Creo también que hemos hecho muy poco en todos los campos. La prueba es que la gente importante, ahora con cuarenta años y pico, no sobra. Sobran los dedos de un pie, que son más pequeños, para contar a los cuarentones importantes. Pero no me haga usted responsable. Yo veo ahora que los jóvenes no saben lo que quieren, y que acabarán tomando esos cascotes que les hemos dejado para construir algo.

SE PROHÍBE LLORAR

-Bien. ¿Por qué le preocupan tanto las furcias? (Prostitutas. Vulgar. Peyorativo.).

-No me preocupan. Me parecen un tipo humano interesante. Me ha preocupado una furcia: ʽMapiʼ; pero ya la he dejado casada y tranquila en mi cuarto libro sobre su vida.

-Pues se han acabado las furcias con lo Love Story… (Exitosa novela de 1970, del profesor universitario y escritor estadounidense Erich Wolf Segal. 1937-2010).

|

Acotación con respecto a “La Sagan” mencionada a continuación: (Probablemente se refiere a la novela Bonjour tristesse, (1954), exitosa en ventas y premios, cuya autora de 18 años de edad, Françoise Quoirez (Françoise Sagan) (1935-2004), integrante de la corriente literaria “Nouvelle Vague” (Nueva Ola), logró fama y fortuna; también se granjeó muchos detractores incluyendo el Premio Nobel de Literatura (1952) François Mauriac. 1885-1970). |

-Eso fue un fenómeno literario incomprensible. Love Story fue y sigue siendo malísima. Yo la leí en inglés y no tiene ningún valor. La Sagan es mucho mejor, sin que la Sagan sea gran cosa. Por lo menos tiene buen leguaje y situaciones con picardía. La única explicación que le encuentro al fenómeno Love Story, fue su propaganda masiva. Yo, si fura editor, no la hubiera admitido jamás. Hubiese metido la pata, claro.

-¿No será que la gente tiene unas ganas de llorar tremendas?

-A la gente lo que le sobran son ocasiones para llorar. Yo no creo que la gente sea tan estúpida como para volver al género romanticoide.

-Pues Nixon dice que lloró a moco tendido…

-Sería por los problemas del Vietnam, porque la novelita es una majadería de campeonato. No está ni siquiera a la altura de un serial de emisora de provincias, ya no digo la emisora nacional. Ni siquiera en la emisora de Bollullos (varias aldeas dispersas) del Jiloca (Comarca rural de Aragón), si la hubiese, se hubieran atrevido a quedar dignamente con las porteras locales radiando una cosa así. (“La emisora del Valle del Jiloca, dirigida por José Luis Campos, lidera la información desde el medio rural”, según El Heraldo de Aragón, del 5 de febrero de 2025; fundado en 1895). Porque toda la gracia de Love Story está en que el muchachito le llama ʽson of a bitchʼ a su padre, y que la muchachita dice mucho ʽmierda de toroʼ. Ni siquiera ʽmierda secasʼ. Fíjese usted si Camilo José Cela edita su ʽSan Camiloʼ) en Estados Unidos sobre esa base. Se hincha. (Cela: Marqués de Iria Flavia desde 1996, miembro de la Real Academia Española, Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras, 1987, Premio Nobel de Literatura 1989 y Premio Cervantes 1995).

-No me negará usted que morirse de leucemia en las páginas finales, es tristísimo…

-Pues Margarita Gautier (cortesana) (La dama de las camelias, 1848, de Alexandre Dumas (hijo). 1824-1895) se moría más dignamente de tuberculosis, sin decir tanta chorrada. Ni siquiera decía ʽmierda de toroʼ. (Injusto. Mentira).

-¿Por qué presume usted de ʽplay boyʼ?

-No; no presumo. Yo trabajo mucho, y para ser ʽplay boyʼ hay que tener mucho dinero y ser más joven que yo. A ʽMapiʼ le hice decir una vez: el ʽplay boy, o sea el joven que juega, acaba convirtiéndose en ʽpay manʼ, o sea el hombre que paga. Lo que pasa es que yo he jugado mucho a hacer frases, a la ʽboutadeʼ, (descalificación a una expresión pretendidamente inteligente) a decir bobadas. Pero yo no soy así.

-Naturalmente, usted es partidario del divorcio.

-Sí, claro. Además, vamos progresando en ese sentido. En el último censo, ya le dejan a uno poner ʽSolteroʼ, ʽCasadoʼ, ʽViudoʼ o ʽSeparadoʼ. En esto del divorcio, ya debemos pensar con la cabeza.

-Pues en Italia, ya ve, no se quiere divorciar nadie…

-Eso será lo que dice Televisión Española… Y si no quieren mejor para ellos. Lo que ceo yo es que la mejor fórmula para mantener la estabilidad y la seguridad de un matrimonio, es la libertad de poder dejarlo. Cuando marido y mujer saben aquello ya no hay quien lo rompa, ocurre que las señoras se ponen gordas; y se dan cremas; y reciben al marido con bigudíes (ruleros). Y los maridos se van de juerga porque saben que aquello no hay quien lo mueva. Los matrimonios se hacen las mayores charradas mutuas porque la situación no tiene remedio. Los novios y los amantes se cuidan¸ se hacen regalos porque quieren conserva el amor y saben que se puede romper. Luego del matrimonio, ni regalos ni nada. Bigudíes, a engordar, y a cremas en la cara…

-¿Por qué habla usted con esa voz? ¿Es que quiere entrar en la Academia?

-Hablo con esta voz porque no tengo otra. Si no tengo voz de marica, y usted perdone, ¿qué le voy hacer? También Caruso, y Monserrat Caballé, estarán muy contentos con su voz… Y además no aspiro a la Academia. Por lo menos no tengo ninguna prisa.

-Pero en el fondo, lo que le gustaría ser sería ejecutivo del desarrollo, ¿no?

-No, tampoco. Se me dan muy las matemáticas, e incluso la gramática. No sé muy bien lo que es un participio pasado, ni cuál es el logaritmo de pi.

-Bien. ¿Cómo será La Codorniz en la Monarquía, Álvaro?

-Igual que siempre, siempre que siga dirigida por mí. Si La Codorniz resultara aburrida, sería porque el país es aburrido. Yo voy errante con el país Lo que sí espero es que la Nueva Monarquía sepa ennoblecer a sus artistas, como lo hacen en Inglaterra. Yo llevo veintiocho años dirigiendo el mismo periódico y nadie me ha dado un cintajo. Parece como si el sistema sólo condecorara a los funcionarios. Eso de que Agatha Christie sea ʽLady Agathaʼ, y que le den medallas a ʽLos Beatlesʼ que han llenado las arcas del Imperio Británico, es hermoso. ¿Cuántos artistas, y escritores españoles, pueden aspirar a eso?... A mi, en definitiva, me preocupa lo que a todos mis compatriotas: el futuro. Que nuestra nueva fórmula del futuro sea joven y comprensiva. Usted les pregunta a los jóvenes: ʽ¿Qué es lo que queréis?ʼ Y sólo saben responder: ʽEsto no nos gustaʼ. Entonces no van a tener más remedio que ir al campo de batalla e ir recogiendo los cascotes para construir algo. Porque en Francia tampoco tienen idea, ni fórmulas nuevas. En Inglaterra están cambiando de época y hay una desorientación tremenda. En Suecia creen que su socialismo les está fallando. Estados Unidos, no digamos. En Rusia se enfrentan con una juventud que empieza a decir que ʽnoʼ, porque ya está harta de decir que ʽsíʼ. Y ya no basta con llamar ʽ´fósilesʼ a los padres. Si no valen estas estructuras, habrá que hacer otras. Pero yo, Álvaro de Laiglesia, no soy político. Afortunadamente para mí y para el humor español contemporáneo”. (6)

OTRA OPINIÓN

“Mihura, De Laiglesia... tenían una capacidad de vivir, de reírse, de pensar, de entrar en todos los debates, que ya no tenemos hoy. En la España nacional, en la España de la posguerra, había censura, pero ahora la censura es autoimpuesta», reflexiona Herreros, que pide que apunte un titular: ʽEl problema es que ahora la gente no se sabe reír. Ahora sólo hay problemas, muertos, preocupaciones...ʼ. (…)

Álvaro de Laiglesia colaboró con Mihura en “El caso de la mujer asesinadita” (1946), una obra de teatro en tres actos que hoy sería impensable no solo publicar, sino también representar. «Daba igual lo que dijera, aunque decía grandes verdades, pero las decía con tal convicción, era un hombre que le ponía tanto énfasis a lo que decía, que le escuchabas. Recreaba las palabras, que se le salían por los ojos, y hablaba con una vitalidad que te comía”. (7)

UNA SEMBLANZA

“Hoy quiero traer a colación a don Álvaro de Laiglesia, el que fuera director de La Codorniz durante treinta y tres años, un fenómeno inaudito en la prensa de nuestro país, y todavía más si hablamos de la prensa humorística, con dictadura incluida. En aquella mítica revista colaboraron muchos escritores y humoristas gráficos de primera línea, aunque, desde la perspectiva actual, su producción haya perdido fuelle. No obstante, y según opinión de Chumy Chúmez, ʽtodo el humor gráfico de los últimos tiempos procede de los antiguos colaboradores de La Codorniz. Los que están renaciendo últimamente son sus nietosʼ. Pero Chumy murió hace más de una década y yo no tengo ni idea de lo que sucede ahora en los quioscos.

Si me cito hoy con Álvaro de Laiglesia es porque ha caído en mis manos la reedición de ʽLa Codorniz sin jaulaʼ (2012), un librito que escribió nuestro autor en 1980, al poco de abandonar la dirección de la revista. En sus páginas, el humorista explica lo que ocurría en La Codorniz cuando él era el director. Con este fin, hace un recuento de las vicisitudes y palos que sufrió la revista a manos de la censura y que culminaron con sendos cierres gubernativos en 1973 y 1975, a cargo de Manuel Fraga. En aquellos años, La Codorniz alcanzaba una tirada semanal de cien mil ejemplares (o más) y cada suspensión de cuatro meses significaba un grave quebranto para su propietario (el conde de Godó) y para su plantilla de colaboradores, que se quedaba sin ingresos.

La Codorniz sin jaula fue el último libro de Álvaro de Laiglesia (escribió más de cuarenta) y también su despedida literaria del mundo de los vivos, pues moriría unos meses después, de forma inesperada, súbita y sin dolor, en Manchester, a los 59 años de edad. La muerte, disfrazada de trombosis, le atacó por la espalda y Álvaro de Laiglesia se desplomó sobre la mesa de un bar sin mediar palabra”. (8)

NOTAS Y REFERENCIAS

1) Freud, Sigmund. El chiste y su relación con lo inconsciente. Biblioteca Nueva. Tercera edición. Tomo I. Página 1036. Madrid, España. 1973.

2) Girones, José Manuel. La política española entre el rumor y el humor. Ediciones Nauta. Páginas 378 y 379. Barcelona, España. 1974.

3) Durante 33 años (1944-1977) fue además director de la revista humorística “La Codorniz” (1941-1978).

4) Laiglesia, Álvaro de. Los pecados provinciales. Editorial Planeta. 8ª edición. Páginas 322 y 323. Barcelona, España. Marzo de 1976.

5) La preposición de antepuesta al apellido indica origen familiar, lugar de nacimiento, antecedente nobiliario, etcétera; a veces es escrito incorrectamente con mayúscula como en este caso y otros similares.

Vale recordar al talentoso novelista y periodista inglés Daniel Foe (1659/1661-1731), firmó anteponiendo “De” a su apellido buscando resaltarlo nobiliariamente según la costumbre de su época; otros compraron títulos generando significativos ingresos a la Corona que, sobre todo, sabía gastar y nunca trabajar.

6) Laiglesia, Álvaro de. Tocata en “ja”. Editorial Planeta. Sexta edición. Páginas 291 hasta 302. Barcelona, España. Diciembre de 1972.

7) Herreros, Enrique. En María Serrano. Los cien años de Álvaro de Laiglesia, el más audaz para el lector más inteligente. El Debate. Madrid, España. 9 de septiembre de 2022.

8) Montaner, Pere. Álvaro de Laiglesia, humorista y seductor. La Charca Literaria. 20 de mayo de 2016.

Álvaro de Laiglesia: who hasn’t read him at some point?

By Alejandro Rojo Vivot

“Our hope that the technique of the joke could not fail to reveal to us its intimate essence leads us, above all, to investigate the existence of other jokes whose formation is similar to that of the one previously examined. In reality, there are not many jokes of this type, but there are enough of them to form a small group characterized by the formation of a mixed word.” (1)

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)

One of the cornerstones of Spanish humor of the twentieth century is the prolific work of the brilliant Álvaro de Laiglesia González, who used several pseudonyms: “Peribáñez”, “El Condestable Azul” and “Alcaponen”. (1922–1981).

Today, reading him again, after so many decades have gone by and other extraordinary exponents have been added, means entering a magnificent creative world with few equals.

There are those who may have done so long ago and who, in these grim times, when they delve into his work will be able, despite everything, to laugh while lifting their gaze towards a hazy or, very often, somber horizon.

Personally, many years ago Laiglesia accompanied us with delight in our first treasured books and led us to begin reflecting on the human capacity to laugh at ourselves.

It is literary humor par excellence, so different from naïve slapstick (humor based on falls and pratfalls).

The age‑old question “what is humor?” still has no single answer, but in the twenty‑first century we have made considerable progress in this regard, since we now undoubtedly know that much is still lacking before the dilemma can be resolved; becoming acquainted with the life and work of humorists is a good path toward that goal, even though it is very long and full of delightful surprises.

“Perhaps the fundamental lesson that the realist mirror leaves us is not to trace reality and produce a document, but rather to set out from the real in order to go much further, sharpening contours in the awareness that pure realism is impossible. As the narrator of Cerca de la ciudad pointed out, one must ‘reinvent neorealism once again’ (Benet, 2012: 267); attain its very aims but by opening up the range of possibilities, combining truth and revelation, admitting more than one reality by looking from more angles, tense, sharp and yet (or perhaps for that very reason) comic.”

Manuela Rodríguez de Partearroyo Grande, Los Ojos de la Máscara. Poéticas del grotesco en el Siglo XX: neorrealismos, expresionismos y nuevas miradas. Complutense University of Madrid, Program in Literary Studies, Faculty of Philology, p. 317. Madrid, Spain, 2015.

A TURN OF THE SCREW

The outstanding Spanish cartoonist Pablo San José García (1926–1998) stated in an interview: “All the humor of our picaresque tradition, acid and gloomy, did it not reflect the most vivid reality of its time? Among us, kindly humor, not to mention poetic humor, has no chance at all when it comes to general consumption. If it is not against something or someone, the audience, disappointed, comments: ‘What nonsense!’ or ‘What rubbish!’.” (2)

In the manner of the eminent exponent of the Renaissance (fifteenth and sixteenth centuries), Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), more often quoted than read, who in 1513 wrote his essay of advice to the Prince, the multifaceted Spanish humorist Álvaro de Laiglesia (3) did something similar for a future monarch and, of course, for all his contemporaries who were enthusiastic about his work.

“Your Highness,

Take care not to acquire a reputation for being funny. In life one may be reputed to be almost anything, but never to be funny. You will say to me: ‘Can one be reputed to be a bore?’ And I will answer: It may seem absurd, but there is no problem in having a reputation for being a bore. But for being funny, I repeat, there is. It is extremely dangerous, not only in your lofty social sphere, but in all of them. I had a friend who had a reputation for being funny and he died of hunger for that very reason. He was a healthy and robust gentleman, I assure you, who could chew grape pips without the slightest effort. He was a happy man, I can swear to it if you deem it necessary. And yet, once – just once – he told a very funny joke, and people began to say that he was very funny. (…)

Do you realize, Your Highness, just how dangerous it is to have a reputation for being funny? (…)

Do you now understand, Your Highness, why you must never acquire a reputation for being funny? For my part, you have been warned. And you already know that a forewarned prince is worth two.” (4)

ALSO

As Félix Cepriá summarized (Tebeosfera, 2008): “Álvaro de Laiglesia González Labarga was a writer and director of the Spanish satirical magazine La Codorniz from 1941 to 1978, imprinting his remarkable inventiveness on ‘the boldest magazine for the most intelligent reader’, which continued to exist in spite of punitive censorship between 1973 and 1975 under Manuel Fraga Iribarne (1922–2012). The regulation was only amended later by Royal Decree‑Law 24/1977.

He began to write humorous pieces at the age of fourteen in Unidad and Fotos; he then became deputy editor of the children’s magazine Flecha (Barcelona, 1937 and 1938). He worked intensely until his unexpected death.

A year later, already as a full‑time author, he served as editor‑in‑chief of the weekly La Ametralladora (1937–1941), which printed 100,000 copies during the Spanish Civil War and was founded by the excellent humorist and playwright Miguel Mihura Santos (1905–1977).

In Cuba he worked for a few months at Diario de la Marina, before Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (1926–2016) did so in his youth, never imagining the subsequent decades in which the power of arms would keep in force an autocratic government, upheld by militarized public employees, after the overthrow of the baleful dictator Sergeant Rubén Zaldívar who, from 1939 on, called himself Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar.

Later, for a short time, he worked on the evening paper Informaciones (1922–1983) at the suggestion of its editor, Víctor de la Serna y Espina (1896–1958). It had a print run of 90,000 copies and its editorial line evolved over time.

He was a remarkably prolific author and in many respects a disruptive one. His command of the language is highly noteworthy, without ever falling into the bottomless labyrinths of banality that are false or unnecessary erudition.

He never sought the degrading, obsequious approval of others, nor the politically correct stance of politically incorrect politicians. If he were alive today, he would probably revise some expressions and personal decisions, but here we remember him without judging, which is already a great deal.

His motto could have been: Humor, without offending or hurting.

All his books were successful, many of them going beyond ten editions at Planeta, Barcelona. For example, Tocata ja reached five printings, each of 3,300 copies, in its first quarter (four in October and one in December).

His titles are humorous, each of them exceeding 200 pages; for the most part they bring together previously published articles; at times they are stories featuring his endearing characters, such as “Mapi”, who appears in a series of four books.

Depending on the source consulted, the total number varies, but in all cases it exceeds thirty.

Un náufrago en la sopa (1944), Todos los ombligos son redondos (1956), El baúl de los cadáveres (1948), La gallina de los huevos de plomo (1950), Se prohíbe llorar (1953), Sólo se mueren los tontos (1954), Dios le ampare, imbécil (1955), Más allá de tus narices (1958), ¡Qué bien huelen las señoras! (1958), En el cielo no hay almejas (1959), Te quiero, bestia (1960), Una pierna de repuesto (1960), Los pecados provinciales (1961), Tú también naciste desnudito (1961), Tachado por la censura (1962), Yo soy Fulana de Tal (1963), Libertad de risa (1963), Mundo, Demonio y Pescado (1964), Con amor y sin vergüenza (1964), Fulanita y sus menganos (1965), Racionales, pero animales (1966), Concierto en Sí amor (1967), Cada Juan tiene su Don (1967), El baúl de los cadáveres (1967), Los que se fueron a la porra (1957), Se busca rey en buen estado (1968), Cuéntaselo a tu tía (1969), Nene, caca (1969), Réquiem por una furcia (1970), Mejorando lo presente (1971), Medio muerto nada más (1971), El sexy Mandamiento (1971), Tocata en ja (1972), Listo el que lo lea (1973), Libertad de risa (1973), Es usted un mamífero (1974), Réquiem por una furcia (1974), Una larga y cálida meada (1975), Cuatro patas para un sueño (1975), El sobrino de Dios (1976), Tierra cachonda (1977), Se levanta la tapa de los sexos (1978), Más allá de tus narices (1978), Los hijos de Pu (1979), Morir con las medias puestas (1980), Mamá, teta (1981), Todos los ombligos son redondos (1982).

In his posthumous work La Codorniz sin jaula (1981) his daughter Beatriz wrote in the post‑mortem prologue: “My father was elegant, generous, handsome and from a good family, and he knew how to make the most of that distance from the everyday that good manners impose. I am convinced that thanks to all this, and to his talent, his capacity for work, his lack of laziness, to Fernando Perdiguero and perhaps a little to his sense of humor, he was able to bring out La Codorniz on the streets for thirty‑odd years. He did so without taking too much to heart the daily battle against censorship, but above all the struggle against those infinite shades of gray that permeated the atmosphere.”

All the volumes published by Planeta are graced with brilliant full‑color dust jackets by the prolific and multi‑award‑winning playwright, cartoonist and journalist Ángel Antonio Mingote Barrachina (1919–2012), first Marquess of Daroca, full member of the Royal Spanish Academy and doctor honoris causa by the University of Alcalá de Henares and by King Juan Carlos University, better known as Mingote, which in itself is a humorous touch.

On several occasions he also collaborated very successfully with texts that were broadcast by Spanish Television.

HIS THOUGHTS ON HUMOR

In this writer’s view, the intelligent interview that Pedro Rodríguez conducted with the author and press executive under discussion here is still little known, even among specialists; in it he sets out his perspective on humor and its practice, adding his views on several other matters: war, divorce, politics, freedom, fake news, respect and appreciation of human diversity, the Academy, and so on. They reflect his own time and it is very likely that, nowadays, he would have altered several points or kept them to himself.

It is a truly valuable document that adds to the relevant bibliography and helps us understand the phenomenon of La Codorniz as a printed graphic‑journalism venture over three long decades.

“BY WAY OF AN EPILOGUE: Álvaro de Laiglesia, in earnest

BONJOUR, TRISTESS…

The first thing you will see is the red pencil, within easy reach, on the bare desk.

Apart from that, allow me to say that you are naïve: nobody laughs at Claudio Coello 46, fourth floor, door on the right, nor are there any little bells, nor any voice out of place. Perhaps it has to be that way: the floor old and creaky; the light dim; the armchairs black; the curtains immaculate; the doorbell like the one at the courthouse. On the other side of the curtains there are men bent over drawing boards, as in the sitting room of a first‑class boarding house, all modern conveniences, homely atmosphere. Like an old blood‑analysis laboratory. By the way, how are you, Mr. de Laiglesia?” (5)

“Very well, thank you. Very pleased to be the longest‑serving editor in Madrid. I have been running the same paper for more than twenty‑eight years, and I am the dean. Beating records is always fun.”

Then he tells you the story of that thirty‑year‑old obstetrician who dyed his hair white and pretended to be rheumatic so that ladies would undress without inhibitions. But we are not going to laugh even once. Perhaps it has to be that way: without a single quail in the friar‑like office; with all the books behind him, lined up like stout ladies in girdles; with his unbearable warm voice; struggling to stop saying “Cela, Dalí”; begging with his eyes not to be asked for boutades, like the baronesses at dessert; this sacred old boy who has spent twenty‑eight years teaching the Koran to this old and sacred country… By the way, what is it you boast about now, Mr. de Laiglesia?”

“I have already told you. I boast of being the Dean. Apart from that, I am happy with life. I have just begun my thirty‑fifth book, all my ideas are intact, and I reckon I will reach sixty or seventy books. I do not believe in the writer of a single little work. I believe that, in order to endure, a writer has to be more abundant, like Victor Hugo, Balzac or Shakespeare.”

“But comparisons are odious, aren’t they?”

“Indeed. They were much older than I am.”

Naturally, he has given instructions that no one is to disturb us…

CROSSED OUT BY THE CENSORS

“Who is behind La Codorniz, Álvaro?”

“By the very fact of being a humorist, one has to be independent. My company has never egged me on or pressured me. A humorist cannot be monarchist, or republican, or falangist. One has to be above it all, in a pink cloud, never a stormy one, observing what is going on. Proof of that independence is that the magazine is still going strong and its editor has not changed. Newspaper editors have changed, ministers have changed, and I could have fallen with one group or another. But it has not been so.”

“What was the worst ordeal, Álvaro?”

“The biggest problems were always technical. (…) Other kinds of obstacles also belong to that period: when the censors crossed out the word ‘liver’ because they said it was in bad taste; when they pulled a photo of an Indian on the grounds that ‘he looked like Jesus Christ’. But I do not brag about that. In this country there has always been a stream of tall tales about La Codorniz that I never wanted to refute because it was extremely effective publicity. La Codorniz is credited with covers and jokes that it never published and never wanted to publish. That thing about ‘The cushion is to an X as…’. Certain weather reports, certain coarse jokes, the business with Columbus’s egg, and many other bits full of naivety and stupidity… In any case, I reckon that in twenty‑eight years I must have had about fifty fines. And in recent times, nothing serious.”

“The subscriptions from Ministries, is that for real?”

“Yes. Believe it. Or at least believe that they read the magazine. Because it is the boldest one, for the most intelligent reader. It seems logical that politicians should read it. But even if there were the greatest freedoms, I would never turn the magazine into a politicized magazine. Humor is above politics.”

“But that is curious. Why have all the newspapers politicized humorists?”

“That is their business, the business of the newspapers. The constraints of the daily press. To be a good humorist you have to be a bit of everything. I am a bit falangist because, indeed, I believe in a short‑skirted, cheerful Spain. I am a bit communist because it strikes me as monstrous that the rights of great writers should expire fifty years after their death while in contrast estates are inherited for ever and ever. I am a bit monarchist because I like good manners and kissing ladies’ hands. I am a bit republican because it is very nice that shopkeepers can become ministers. I am a bit democrat because I am amused that problems can be solved by voting… In other words, a humorist has to take those little bits, the best of each system. Now then, La Codorniz is the only ‘pure’ humor magazine in Europe. In Italy it became ‘pure’ under Mussolini, because political humor was impossible there.”

“What was the most outrageous thing you ever published, Álvaro?”

“Well, the most outrageous… I am not sure. What upset me most was that parody we did of Arriba. Nowadays nothing would have happened, but at that time certain subjects were untouchable. The country really has moved on a lot. In any case, the fear there was in those years of the humor of La Codorniz always struck me as excessive. With my team I would have gone a bit further, had there not been a Censorship preventing us. Humor cannot do any harm. It must be taken as a balm that heals, not as a corrosive. In France, in England, in Germany there are no limits on humor, because they know that humor does not topple regimes or corrupt the people.”

“Overall, are censors harder to deal with than ladies?”

“Nobody finds censors easy to deal with. We need to become more tolerant in this country. I remember that when I was in Copenhagen I was walking past the Royal Palace and suddenly a car came out of the palace with King Frederick IX inside, on his way into town to do some shopping. To buy socks or shaving cream. Well, fine. And yet I remember going to Málaga for Holy Week and seeing the road full of policemen because a minister was on the move. These little deifications are not normal by European standards. We must get used to seeing politicians as civil servants, more or less well paid, who more or less competently manage our affairs. But here we still go round shouting ‘Don So‑and‑So, that’s who I am’… Truly, we need to learn how to laugh at ourselves.”

THOSE WHO WENT DOWN THE DRAIN

“Have you not noticed, Álvaro, that the country seems less inclined to laugh?”

“If it is not inclined, it must dredge up the inclination from somewhere. Because every country has its problems. They may be richer than we are, but they have their own good problems. What we have to do here is organize the opposition. I believe the great solution for the country is to create the ‘Opos’ party.”

“The what…?”

“The ‘Opos’, short for ‘Oposición’ [Opposition]. No, it is not a joke. In England their Opposition is organized in such a way that one party is in Power and the rest are in the Opos. I say that here there are a few Spaniards in Power and the rest are in the Wanting. Well then. With the Opos we would have a contrast of opinions. Part of the country would be the Opos, and that would be the way to establish a dialogue. To play pelota against a wall you need a wall, because if not, the balls, as happens now, get lost in the sea. The Opos would be a system of systole and diastole to establish balance. It would be the wall of the system. And when the gentlemen in Power left office, they would move over to the Opos. And so on… And note that I call it Opos because ‘Opposition’ is such a long word…”

“All right, fine. But, Álvaro, isn’t the Spaniard still short and with a very bad temper?”

“Life in countries that are still poor – and to understand ours it is enough to look at it from the air, ignoring the coastal belt – is tougher. Our problems, until not so long ago, were problems of a crust of bread. Other countries have television problems and that makes their humor gentler. But I do not think Spaniards are by nature short and sour; rather, it is due to the living conditions they have had. Besides, the present generation drinks plenty of milk and takes lots of vitamins.”

“Has the country repaid the services rendered by humorists?”

“Nothing is owed to humorists. I do not aspire to having a ‘message’. I simply tell what I see. We are no one’s apostles and no one’s devotees. We do no harm. I do not operate on society’s tumors; I merely give them a sedative. Not even in a given period were we the ones who could criticize the system. We criticized life. Now they tell me that La Codorniz is read less at the university.”

“Is Russia to blame, Álvaro?”

“We are all to blame. How many movements that fought against this and against that are now on the side of this and that? Neither Russia nor the United States are ‘the culprits’. You and I are just as much to blame as Mao, because between us all we have created a world in which dangerous characters have been able to flourish.”

“But you have never regretted having been in the Blue Division?”

“Well, I have already explained that once: I went to Russia because I was in love with a Slavic woman. Also because it was a great European adventure for an eighteen‑year‑old lad. But, basically, I went because I wanted to see someone who was somewhere near there, but I never found her.”

“Have you never cashed in on it?”

“No, absolutely not. I have not even worn the medals I won.”

“In the end, did your generation go down the drain politically?”

“Truthfully, we do not have many things we can boast about. But that is because ideals have fallen on hard times all over the world. I liked José Antonio for what he said about the ‘useless crusts’ that had to fall away. Perhaps this civilization will be saved not by a brand‑new construction but by what can be built with the rubble we have left strewn over the battlefield. A stone here, another relic there, a reminder of some new system. In any case, the truth is that I took no part in my generation’s political concerns. I also think we have done very little in every field. Proof of that is that there is no glut of important people now in their early forties. The toes of one foot – which are smaller – are enough to count the important forty‑somethings. But do not hold me responsible. I can see that young people today do not know what they want and that they will end up taking those bits of rubble we have left them and building something with them.”

NO CRYING ALLOWED

“Right. Why are you so interested in tarts?” (Prostitutes. Colloquial. Pejorative.)

“I am not ‘interested’ in them. I find them an interesting type of human being. One tart has concerned me: ‘Mapi’; but I have already married her off and left her at peace in my fourth book about her life.”

“Well, the tarts have disappeared with Love Story…” (The successful 1970 novel by American professor and writer Erich Wolf Segal, 1937–2010).

[Clarifying note on “La Sagan”: It probably refers to the novel Bonjour tristesse (1954), a best‑seller and prize‑winner whose 18‑year‑old author, Françoise Quoirez (Françoise Sagan, 1935–2004), a member of the “Nouvelle Vague” literary trend, achieved fame and fortune, and also attracted many detractors, including the 1952 Nobel laureate François Mauriac, 1885–1970.]

“That was an incomprehensible literary phenomenon. Love Story was and still is dreadful. I read it in English and it has no merit whatsoever. Sagan is much better, without Sagan being anything great. At least she has good language and situations with a touch of sauciness. The only explanation I can find for the Love Story phenomenon is its massive publicity campaign. If I were a publisher, I would never have accepted it. I would have made a blunder, of course.”

“Isn’t it just that people have an overwhelming urge to cry?”

“What people have in abundance are occasions for crying. I do not believe people are so foolish as to go back to the romantic‑kitsch genre.”

“Well, Nixon says he bawled his eyes out…”

“That must have been because of the Vietnam problem, because the little novel is an out‑and‑out piece of rubbish. It does not even reach the level of a radio serial on a provincial station, let alone a national station. Not even at the station in Bollullos‑del‑Jiloca, if there were one, would they have dared, out of respect for the local janitresses, to broadcast such a thing.” (“The Jiloca Valley radio station, directed by José Luis Campos, leads the field in rural news coverage”, according to El Heraldo de Aragón, 5 February 2025, founded in 1895.) “Because the whole charm of Love Story lies in the boy calling his father ‘son of a bitch’, and the girl saying ‘bullshit’ all the time. Not even just ‘shit’. Imagine if Camilo José Cela were to publish his San Camilo in the United States on that basis. He would make a killing.” (Cela: Marquess of Iria Flavia from 1996, member of the Royal Spanish Academy, 1987 Prince of Asturias Award for Literature, 1989 Nobel Prize in Literature and 1995 Cervantes Prize.)

“You cannot deny that dying of leukemia in the last pages is terribly sad…”

“Well, Marguerite Gautier, a courtesan (in The Lady of the Camellias, 1848, by Alexandre Dumas fils, 1824–1895), died much more decorously of tuberculosis without uttering so many stupidities. She did not go around saying ‘bullshit’. (Unfair. Untrue.)”

“Why do you boast of being a playboy?”

“I do not boast. I work hard, and to be a playboy you need a lot of money and to be younger than I am. I once had Mapi say: the ‘play boy’, that is, the young man who plays, ends up turning into the ‘pay man’, that is, the man who pays. What has happened is that I have played a great deal at coining phrases, at boutades, at talking nonsense. But I am not really like that.”

“Of course, you are in favor of divorce.”

“Yes, of course. And we are making progress in that regard. In the latest census they already let you tick ‘Single’, ‘Married’, ‘Widowed’ or ‘Separated’. On the subject of divorce we need to use our heads.”

“Well, in Italy, as you see, nobody wants to get divorced…”

“That is what Spanish Television says… And if they do not want to, so much the better for them. What I see is that the best way to maintain the stability and security of a marriage is the freedom to be able to end it. When a husband and wife know that there is nothing that can break the bond, then the women put on weight, slather on face cream and receive their husbands in hair rollers. And the husbands go out on the town because they know nothing can shake the situation. Husbands and wives do the worst things to each other because the situation has no solution. Sweethearts and lovers, on the other hand, take care of themselves and give presents because they want to keep love alive and know it can be broken. After marriage there are no presents or anything. Just rollers, putting on weight and face cream…”

“Why do you talk in that voice? Is it because you want to enter the Academy?”

“I talk in this voice because I have no other. If I sound a bit camp, with all due respect, what am I to do about it? Caruso and Montserrat Caballé, for their part, will be delighted with their voices… And besides, I am not aiming for the Academy. At least, I am in no hurry.”

“But deep down what you would like is to be a development executive, right?”

“No, neither. I am no good at mathematics or even at grammar. I do not really know what a past participle is, nor what the logarithm of pi is.”

“Right. What will La Codorniz be like under the Monarchy, Álvaro?”

“Just the same as always, as long as I remain its editor. If La Codorniz were to become boring, it would be because the country is boring. I wander along with the country. What I do hope is that the New Monarchy knows how to ennoble its artists, as they do in England. I have been editing the same paper for twenty‑eight years and no one has given me even a ribbon. It seems as though the system only decorates civil servants. The fact that Agatha Christie is ‘Lady Agatha’, and that they pin medals on the Beatles, who have filled the coffers of the British Empire, is wonderful. How many Spanish artists and writers can aspire to that?... Ultimately, I am concerned about what worries all my fellow countrymen: the future. That our new formula for the future should be young and understanding. If you ask young people ‘What do you want?’, their only answer is ‘We do not like this’. So they will have no choice but to go out onto the battlefield and start picking up the rubble to build something. Because in France they have no ideas or new formulas either. In England they are changing eras and there is tremendous confusion. In Sweden they think their socialism is failing them. The United States, even more so. In Russia they are faced with a youth that is beginning to say ‘no’, because it is tired of saying ‘yes’. And it is no longer enough to call their parents ‘fossils’. If these structures are no good, new ones will have to be created. But I, Álvaro de Laiglesia, am not a politician. Fortunately for me and for contemporary Spanish humor.” (6)

ANOTHER OPINION

“Mihura, de Laiglesia… they had a capacity for living, for laughing, for thinking, for taking part in every debate, that we no longer possess today. In Nationalist Spain, in post‑war Spain, there was censorship, but now censorship is self‑imposed,” reflects Herreros, who insists on a headline: “The problem is that nowadays people do not know how to laugh. Now there is only trouble, death, worries…” (…)

Álvaro de Laiglesia collaborated with Mihura on El caso de la mujer asesinadita (1946), a three‑act play which today would be unthinkable, not only to publish but also to stage. “It did not matter what he said – though he told great truths – because he said it with such conviction; he was a man who put such emphasis into what he said that you listened to him. He brought words to life, they spilled out of his eyes, and he spoke with a vitality that swallowed you up.” (7)

A PORTRAIT

“Today I would like to bring up Don Álvaro de Laiglesia, who was director of La Codorniz for thirty‑three years, an unheard‑of phenomenon in our country’s press, and even more so if we are speaking of the humorous press, dictatorship included. Many top‑flight writers and cartoonists contributed to that legendary magazine, even though, from today’s perspective, their output may have lost steam. Nevertheless, in Chumy Chúmez’s opinion, ‘all recent graphic humor comes from the former contributors to La Codorniz. Those who are now being reborn are their grandchildren’. But Chumy died more than a decade ago and I have no idea what is happening on newsstands today.

I have made today’s appointment with Álvaro de Laiglesia because the re‑edition of La Codorniz sin jaula (2012) has fallen into my hands, a little book that our author wrote in 1980, shortly after leaving the magazine’s editorship. In its pages the humorist explains what went on at La Codorniz while he was the editor. To that end he recounts the vicissitudes and blows the magazine suffered at the hands of censorship, culminating in two government‑ordered closures in 1973 and 1975 under Manuel Fraga. In those years La Codorniz reached a weekly print‑run of one hundred thousand copies (or more), and each four‑month suspension meant a serious setback for its owner (the Count of Godó) and for its staff of contributors, who were left without income.

La Codorniz sin jaula was Álvaro de Laiglesia’s last book (he wrote more than forty) and also his literary farewell to the world of the living, for he would die a few months later, unexpectedly, suddenly and without pain, in Manchester, at the age of fifty‑nine. Death, disguised as a thrombosis, struck him from behind and Álvaro de Laiglesia collapsed wordlessly onto the table of a bar.” (8)

NOTES AND REFERENCES

Freud, Sigmund. El chiste y su relación con lo inconsciente. Biblioteca Nueva, third edition, vol. I, p. 1036. Madrid, Spain, 1973.

Gironés, José Manuel. La política española entre el rumor y el humor. Ediciones Nauta, pp. 378–379. Barcelona, Spain, 1974.

For thirty‑three years (1944–1977) he was also editor of the humor magazine La Codorniz (1941–1978).

Laiglesia, Álvaro de. Los pecados provinciales. Editorial Planeta, 8th ed., pp. 322–323. Barcelona, Spain, March 1976.

The preposition de prefixed to the surname indicates family origin, place of birth, noble background, etc.; it is sometimes incorrectly written with a capital letter, as in this case and others like it. It is worth recalling that the gifted English novelist and journalist Daniel Foe (1659/1661–1731) signed his name with “De” before his surname in order to ennoble it, following the custom of his time; others bought titles, generating significant income for the Crown, which above all knew how to spend and never how to work.

Laiglesia, Álvaro de. Tocata en “ja”. Editorial Planeta, 6th ed., pp. 291–302. Barcelona, Spain, December 1972.

Herreros, Enrique, cited in María Serrano, “Los cien años de Álvaro de Laiglesia, el más audaz para el lector más inteligente”, El Debate. Madrid, Spain, 9 September 2022.

(This text has been translated into English by ChatGPT)