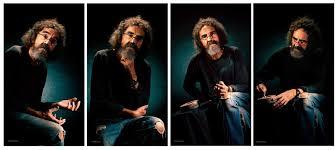

Moisés Rodríguez es el invitado de hoy para que me acompañe en este vis a vis con la vis cómica”.

Para los lectores de Humor Sapiens que no lo conozcan, trataré de presentarlo a mi manera; es decir, poco formal y muy emocionalmente.

Lo conocí en la Enseñanza Media en los años 60. Enseguida tuvimos química y nos hicimos amigos. Recuerdo que lo miraba con admiración porque era todo un personaje entre nosotros. No se distinguía por respetar normas, no sentía pudor por cantar sus graciosas canciones donde quiera, en voz bien alta y actuadas, inventaba historias y las contaba como si fueran anécdotas que hubiera vivido pocas horas antes. En cierto momento creamos el espacio del chiste y en cada recreo nos juntábamos un grupo en corro, en una esquina del patio, a contarlos. Nos esforzábamos por aprender nuevos en el resto del día para poder contarlos en esos recreos. Moisés era el Rey y el Bufón ahí. Yo apenas era un miembro más de la Corte. Pero eso nos hermanó bastante. Recuerdo una tarde calurosa en que caminábamos al salir de la “Secundaria No.1”, como se llamaba nuestro centro educativo, en que tomamos la decisión de que cuando “fuéramos grandes”, publicaríamos una antología universal de chistes. ¿Premonición? Porque no hicimos eso, pero sí fundamos la Seña del Humor de adultos.

Después pasamos por el preuniversitario y Moisés reforzó mucho su imagen de cómico original e ingenioso.

Mientras yo terminaba Ingeniería Civil, él se graduaba de Licenciado en Pedagogía, Mención en Literatura. En la Universidad extendió su fama de cómico a todas las Facultades. Sus historias son increíbles. No exagero.

Y nuestra amistad siempre en aumento.

Ya trabajando en nuestras profesiones en la ciudad de Matanzas, me hago amigo de otro ser fuera de serie, pero muy diferente en cuanto a personalidad, el señor Aramís Quintero, Licenciado en Letras Hispánicas y laureado poeta y escritor. Claro, en cuanto al sentido del humor los tres estábamos en frecuencia.

Un día de 1982 nos juntamos a divertirnos, sin pensar en nada más; es decir, sin proyecciones como humoristas profesionales y alrededor de un piano tocado por Aramís, con las canciones características de Moisés y mis humildes aportes fundamos el grupo “Nosotros” (desconocíamos que en La Habana había un grupo de humor literario que se nombraba “Nos y Otros”. Con el tiempo, cuando incursionaron en el teatro, nos hicimos amigos).

Pero “Nosotros” no llegó a debutar. Sin embargo, fue el antecedente del grupo “Tubería de Media Pulgada”, de humor literario y gráfico, en 1983. Al año de publicar una página completa dominical en el Suplemento Yumurí del Diario Girón de Matanzas, Moisés, Aramís y yo, más un grupo numerosos de colegas, fundamos La Seña del Humor. Al poco tiempo el grupo se achicó, se consolidó, se hizo “nacional” y Moisés siempre fue el hombre con más vis cómica de todos nosotros. Salía a escena y sin hacer nada, la gente comenzaba a reír a carcajadas. No exagero.

La Seña del Humor hizo historia en el humor cubano. Pero se fue desangrando con la salida del país de la mayoría de sus miembros, hasta que Moisés quedó solo y tuvo que hacer (y hace) lo inimaginable para que el legado del grupo no se perdiera.

A partir de ahí desarrolló una tremenda carrera como solista, sobre todo en televisión y radio.

Moisés Rodríguez es uno de los artistas cubanos más queridos por su pueblo. Y no solo por su calidad humorística, sino porque nunca perdió su humildad, su sensibilidad, su sencillez y calidez humana. No exagero.

De más está decir que sigue y seguirá siendo uno de mis mejores amigos. Por eso es un orgullo tener este vis a vis con él en este espacio.

Comenzamos entonces…

PP: Eras un responsable profesor universitario, estudioso de la literatura, etc., pero de pronto aparece “Tubería de Media Pulgada” y después “La Seña del Humor”. ¿Piensas que te cambió la imagen de académico entre tus estudiantes y tus pares? ¿Cómo manejaste esa situación?

MOISÉS: Evidentemente, pero en ambos casos se impuso el profesionalismo (inconsciente). Cosa curiosa: en el ámbito docente me llamaban “el humorista” y entre los humoristas me llamaban “el profesor”. Por supuesto que de esta doble condición tengo todo un arsenal de anécdotas y quizás algún momento desafortunado.

PP: Soy testigo de varias, sin contar las que me has contado. Sin embargo, también hay que decir que tus alumnos siempre decían que eras muy gracioso y simpático. y los humoristas decían que eras un académico serio. Pero sigamos. ¿Cómo fue dejar todo lo que habías estudiado y abrazar la profesión de humorista? ¿La incidencia del cambio en la familia? Por último, ¿qué importancia le das al humor en tu trabajo y en tu vida?

MOISÉS: Siempre me la he jugado a la doble y triple profesión. Primero como profesor universitario y humorista; después como crítico de arte y humorista y ahora como crítico de arte, pintor, y mucho menos humorista activo, cuando he llegado a los 71 años de edad…

La familia siempre ha sido la más afectada. Por mis ejercicios como humorista, por mis sostenidas ausencias del hogar de tantas giras y grabaciones de televisión y radio en programas habituales. Además, a mi familia no le gusta salir conmigo, porque constantemente la gente nos interrumpe para hacerme comentarios sobre mi “trabajo”…

El humor como forma de pensamiento es un factor de identidad que me distingue, y resulta ser que me pagan por “eso” (le agradezco a Dios que me haya dado ese “don”, que me ha abierto tantas puertas… y que escasea tanto).

PP: Yo añadiría que te graduaste de constructor, porque tu casa la hiciste con tus manos desde los cimientos hasta las terminaciones. Siempre te admiré por hacer tantas cosas. Yo no podría. Pero hablemos de nuestro grupo. Sabemos que tu trabajo en La Seña del Humor se divide en dos partes: antes de 1992 y después de ese año. ¿Cuáles fueron las diferencias de ambos trabajos? ¿Disfrutaste más, o disfrutaste menos, esa segunda etapa?

MOISÉS: Para mí no se han tratado de dos momentos, sino de tres:

Uno, cuando tú abandonas el grupo rumbo a Chile, siendo el que había creado, fundado y dirigido La Seña del Humor, y “monstruo creativo todo terreno”. Dos, cuando Aramís se va para Chile, otro señor y amigo de sobrado talento. Y tres, cuando yo, inercialmente, hago estirar los ecos de La Seña hasta sus estertores (finalmente hice una carrera larga en solitario, fundamentalmente en televisión).

PP: Gracias por lo que me toca. Pero quiero ahora que hagas un distanciamiento, alejándote de tu calidad de fundador y miembro de nuestro grupo y me resumas los logros de La Seña del Humor, su aporte, su impacto en la sociedad cubana.

MOISÉS: La Seña del Humor, sin proponérselo, funda y desata todo un Movimiento, que se llamaría después “Movimiento del Nuevo Humor Cubano”, al introducir una renovación en los códigos y presupuestos estéticos de la escena humorística nacional. Ello se tradujo en la eclosión de grupos diseminados por todo el país, con la misma experiencia generacional y discurso escénico humorístico similar.

PP: Es cierto, sin proponérselo se arma con ella un fenómeno nacional con el surgimiento de muchísimos jóvenes humoristas, sobre todo de origen universitario. Pero dicen varios colegas y opinólogos del medio que además de eso, La Seña marcó un hito en la Historia del humor cubano. No lo digo yo, repito lo que he escuchado y leído. Ahora, ¿piensas que fue en realidad un movimiento estético lo que surgió en los años 80, un Movimiento como el de la Nueva Trova, o algo así?

MOISÉS: Evidentemente, en la medida que marcó nuevos derroteros en la escena humorística cubana, en tanto respondió a una nueva manera de pensar, decir y hacer humor…

PP: Vamos entonces a los que sucedió después de aquella "Belle Époque" del humor cubano. Quizás después de la caída del Muro de Berlín muchos colegas comenzaron a hacer un humor más “fácil” (por llamarlo así), por supervivencia y para llegarle a más públicos. En mis estudios he comprobado que el humor obsceno, vulgar, simplista y burlón es el más abundante, consumido y apetecido en todos los pueblos y en todas las épocas (incluso el primer chiste que se registra está en esa cuerda). Es larga la explicación, pero es así. Entonces, dame tu opinión sobre el humor que se hacía en los años 80 y el que se hizo después.

MOISÉS: En Cuba nunca se cayó el Muro de Berlín, pero sí provocó el agravamiento de la situación económica, que a la postre ha determinado el desplazamiento de humoristas hacia los centros nocturnos, en busca de mejor remuneración y su consecuente deterioro del discurso humorístico. Verdadera excepción han sido los Festivales Nacionales “Aquelarres”, que poco a poco han ido perdiendo el apoyo y promoción institucional oficial. A todo ellos habría que añadir la creciente emigración de humoristas.

En los años 80 todavía existían motivaciones profesionales con apoyo institucional y que se ha ido perdiendo hasta llegar a la actualidad, en que predomina un cansancio nacional, provocado por la falta de perspectiva existencial.

PP: ¿Te hubiera gustado que la Seña hubiera seguido como iba en 1991? ¿Te hubiera gustado que se hubiese proyectado internacionalmente?

MOISÉS: Por supuesto que sí, pero eso es absurdo siquiera pensarlo.

PP: Me encanta el absurdo, Móise. Oye, pero, ¿crees que La Seña hubiera podido surgir en Cuba en estos tiempos? ¿Crees que funcionaría nuestro humor en la actualidad?

MOISÉS: Por supuesto que no, nada que ver aquellos tiempos, impensable.

Aunque estoy convencido de que sí funcionaría, lo he constatado en reposiciones que he hecho en numerosos teatros, sus temas y códigos universales siguen siempre vigentes y efectivos.

PP: Yo también lo he comprobado con públicos de varios países y funciona perfectamente. Una lástima que no hayamos podido continuar. Pero dejo La Seña para preguntarte: En varios países de América Latina se dice: "Mi país es un pueblo de humoristas", "en mi país, tú mueves una piedra y sale un humorista", etc. , ¿para ti en Cuba se dice lo mismo?

MOISES: Si todos reclaman este patrimonio será porque poseer sentido del humor parece ser de un atractivo especial. En el caso del cubano específicamente, ya sabes que el "choteo" sí ha sido un mecanismo de defensa para "escapar" de sus desgracias. El cubano será ocurrente y chistoso, pero de ahí no pasa. No obstante hayan existido muy buenos creadores humorísticos y comediantes excelentes en cualquiera de los géneros: literatura, artes escénicas, gráfica, la música, cine...

PP: ¿Es verdad la acuñada frase: "Es más fácil hacer llorar que hacer reír?

MOISES: Si te refieres al caso de la literatura dramática, entiéndase obra teatral, guión escénico, etc., entonces te diría que en la evolución del teatro, primero fue la tragedia, después el drama y por último la comedia, como forma superior de pensamiento, de lo cual se puede inferir que el ingenio capaz de producir risa y reflexión, obedecen a formas superiores del pensamiento humano. Luego entonces hacer reír con el añadido de hacer reflexionar, supone un proceso creativo más complejo, donde se desmonta una realidad hasta crear una nueva forma de realidad que haga reír, pero que a la vez nos haga reflexionar. En realidad de lo que se trata es de que la gente prefiere reír (o sonreír) a llorar, pues para la mayoría, tragedia es lo que vivimos cada día, y por supuesto que no me refiero al ingenio humorístico como forma de evasión de la realidad, sino como asunción de una realidad analizada, generalizada.y proyectada hacia una nueva dimensión... Yo creo que ambos sabemos perfectamente que el hecho mismo de reír supone una mejor salud mental y emocional y un mejoramiento de la conducta humana.

PP: Ahora vuelvo a ti. ¿Estás consciente de que eres una figura muy destacada en la historia del humor cubano, tanto por tu labor en La Seña como por tu carrera como solista después?

MOISÉS: Aunque nunca me lo propuse, y a pesar de los premios y distinciones que me han otorgado, lo que más aprecio, lo que más me satisface, es que a cada paso que doy, recibo el cariño, respeto y admiración de las más disímiles personas, de todos los sectores de la población. Ese es mi mayor orgullo.

PP: Te entiendo perfectamente. Además, te lo mereces. Y para finalizar, ¿qué te gustaría hacer dentro del humor que no hayas hecho hasta ahora?

MOISÉS: ¡Cine!

PP: ¡Lo que se están perdiendo los directores de cine! Para cerrar entonces este “diáloco”, ¿se te ocurre una pregunta que deseaste te hubiera hecho? Y si es así, ¿puedes responderla aquí y ahora?

MOISÉS: La pregunta sería: “¿Qué significó para mí La Seña del Humor? Y te respondería: “Este soberbio proyecto ha representado para mí, sobre todo, iniciación, escuela, ejercicio, herencia, código, carácter, identidad, estandarte y especialmente… nostalgia de todos ustedes que ahora viven en el “más allá”.

PP: Vivamos donde vivamos, por lo menos yo, sigo estando en La Seña del Humor y sigo siendo tu compañero y amigo. Gracias por todo, hermano mío, incluyendo las gracias por este vis a vis.

MOISÉS: Gracias a ti, Pelayo y que sigas teniendo éxitos sostenidos en cada uno de tus proyectos.

PP: Te deseo lo mejor del mundo, mucha salud, muchos éxitos más y abrázame a tu familia, que la siento siempre como mía. Y no exagero.

Interview with Moisés Rodríguez

By Pepe Pelayo

Humor is a factor of identity that distinguishes me, and it turns out that they pay me for "it."

Moisés Rodríguez is today's guest to join me in these "Dialogues with comedians."

For Humor Sapiens readers who don't know him, I'll try to present him in my own way; that is to say, little formal and very emotionally.

I met him in high school in the 1960s. We immediately had chemistry and became friends. I remember looking at him with admiration because he was quite a character among us. He did not stand out for respecting rules, he did not feel ashamed to sing his funny songs wherever he wanted, he made up stories and told them as if they were anecdotes that he had lived a few hours before. At a certain point we created the joke space and at each recess a group would gather in a circle, in a corner of the patio, to count them. We made an effort to learn new ones in the rest of the day to be able to count them in those breaks. Moses was the king and the jester there. I just the counselor of the Crown. But that brought us closer. I remember one hot afternoon when we were walking out of “Secundaria No.1”, as our educational center was called, in which we made the decision that when “we grew up”, we would publish a universal anthology of jokes. Premonition? Because we didn't do that, but we did found Seña del Humor for adults.

Then we went through high school and Moisés greatly reinforced his image as an original and witty comedian.

While I was finishing Civil Engineering, he was graduating with a Bachelor's Degree in Pedagogy, Mention in Literature. At the University he spread his fame as a comedian to all the Faculties. Their stories are incredible. I'm not exaggerating.

And our friendship always growing.

Already working in our professions in the city of Matanzas, I became friends with another being out of the ordinary, but at the opposite pole of Moisés in terms of image, Mr. Aramís Quintero, Bachelor of Hispanic Letters and laureate poet and writer. Of course, in terms of sense of humor, the three of us were in frequency.

One day in 1982 we got together to have fun, without thinking about anything else; that is to say, without projections as comedians and around a piano played by Aramís, with the characteristic songs of Moisés and my humble contributions, we founded the group “Nosotros” (we were unaware that in Havana there was a group of literary humor called “Nos y Others.” Over time we became friends and companions).

But "We" did not make its debut. However, it was the antecedent of the group "Tubería de Media Pulgada", of literary and graphic humor that we put together with Moisés, Aramís and the architect July from the city of Cárdenas, in 1983. A year after publishing a full page Sunday in the Supplement Yumurí from the Diario Girón de Matanzas, Moisés, Aramís and I, plus a huge group of colleagues, founded La Seña del Humor. Soon after the group was consolidated, it became "national" and Moisés was always the man with the most comical face of all of us. He would go on stage and without doing anything, people would start laughing out loud. I'm not exaggerating.

La Seña del Humor made history in Cuban humor. But most of its members emigrated from the country and Aramís was first with Moisés, Leandro Gutiérrez and Adrián Morales. Then Moisés and Adrián remained and in the end the great group La Seña del Humor was reduced to only Moisés, who did (and does) the unimaginable so that the group's legacy would not be lost.

From there he developed a tremendous career as a soloist in the theater, but especially on television and radio.

Moisés Rodríguez is one of the Cuban artists most loved by the people. And not only because of his humorous quality, but because he never lost his humility, his sensitivity, his simplicity and human warmth.

It goes without saying that he continues and will continue to be one of my best friends. That is why it is a pride to "dialogue" with him in this space.

Let's start then...

PP: You were a responsible university professor, a scholar of literature, etc., but suddenly “Tubería de Media Pulgada” appeared and then “La Seña del Humor”. Do you think the image of an academic has changed for you among your students and your peers? How did you handle that situation?

MOISÉS: Obviously, but in both cases (unconscious) professionalism prevailed. Curious thing: in the teaching field they called me “the humorist” and among the humorists they called me “the professor”. Of course, I have a whole arsenal of anecdotes about this double condition and perhaps some unfortunate moment.

PP: What was it like to leave everything you had studied and embrace the profession of humorist? The incidence of change in the family? Lastly, how important is humor in your work and in your life?

MOISÉS: I have always risked double and triple profession. First as a university professor and humorist; later as an art critic and humorist and now as an art critic, painter, and much less an active humorist, when I have reached 71 years of age...

The family has always been the most affected. For my exercises as a comedian, for my sustained absences from home from so many tours and television and radio recordings in regular programs. Also, my family doesn't like hanging out with me, because people are constantly interrupting us to make comments about my “work”…

Humor as a way of thinking is an identity factor that distinguishes me, and it turns out that I get paid for "it" (I thank God for giving me that "gift", which has opened so many doors for me... and which is so scarce ).

PP: Your work at La Seña del Humor is divided into two parts: before 1992 and after that year. What were the differences between the two jobs? Did you enjoy more, or did you enjoy less, that second stage?

MOISÉS: For me it hasn't been about two moments, but three:

One, when you leave the group for Chile, being the one who had created, founded and directed La Seña del Humor, and "all terrain creative monster". Two, when Aramís leaves for Chile, another gentleman and friend with plenty of talent. And three, when I, inertially, stretch the echoes of La Seña to its death throes (in the end I had a long solo career, mainly on television).

PP: I want you to distance yourself from your status as founder and member of our group and summarize for me the achievements of La Seña del Humor, its contribution, its impact on Cuban society.

MOISÉS: La Seña del Humor, without intending to, founded and unleashed an entire Movement, which would later be called the “Movement of the New Cuban Humor”, by introducing a renewal in the aesthetic codes and assumptions of the national humorous scene. This resulted in the emergence of groups scattered throughout the country, with the same generational experience and similar humorous stage discourse.

PP: Do you think that it was really an aesthetic movement that emerged in the 80s, a movement like Nueva Trova, or something like that?

MOISÉS: Obviously, to the extent that it marked new paths in the Cuban humorous scene, insofar as it responded to a new way of thinking, saying and doing humor...

PP: Perhaps after the fall of the Berlin Wall, many colleagues began to make "easier" humor (to call it that), for survival and to reach more audiences. In my studies I have verified that obscene, vulgar, simplistic and mocking humor is the most abundant, consumed and coveted in all towns and at all times (even the first joke that is recorded is on that string). The explanation is long, but it is so. So, give me your opinion about the humor that was made in the 80s and the one that was made after.

MOISÉS: The Berlin Wall never fell in Cuba, but it did cause the worsening of the economic situation, which has ultimately led to the displacement of comedians to nightclubs, in search of better remuneration and the consequent deterioration of humorous discourse. A true exception have been the National "Coven" Festivals, which little by little have been losing official institutional support and promotion. To all of them we should add the growing immigration of comedians.

In the 80s there were still professional motivations with institutional support and that has been lost until today, when a national fatigue predominates, caused by the lack of existential perspective.

PP: Would you have liked that Seña had continued as it was in 1991? Would you have liked it to have been screened internationally?

MOiSÉS: Of course I do, but that's absurd to even think about it.

PP: Do you think that La Seña could have emerged in Cuba in these times? Do you think our humor would work today?

MOISÉS: Of course not, nothing to do with those times, unthinkable.

Although I am convinced that it would work, I have verified it in reruns that I have done in numerous theaters, its themes and universal codes are always valid and effective.

PP: Are you aware that you are a very prominent figure in the history of Cuban humor, both for your work in La Seña and for your career as a soloist later?

MOISÉS: Although I never set my mind to it, and despite the awards and distinctions that I have been awarded, what I appreciate the most, what satisfies me the most, is that with every step I take, I receive the love, respect, and admiration of the most dissimilar people from all sectors of the population. That is my greatest pride.

PP: What would you like to do in humor that you haven't done so far?

MOISÉS: Cinema!

PP: To close this “dialogue”, can you think of a question that you wish I had asked you? And if so, can you answer it here and now?

MOISÉS: The question would be: “What did La Seña del Humor mean to me? And I would answer: “This superb project has represented for me, above all, initiation, school, exercise, inheritance, code, character, identity, banner and especially… nostalgia for all of you who now live in the “beyond”.

PP: No matter where we live, at least I'm still in La Seña del Humor and I'm still your partner and friend. Thank you for everything my brother, including thank you for this conversation.

MOISÉS: Thanks to you, Pelayo, and may you continue to have sustained successes in each of your projects.

PP: I wish you the best in the world, good health, many more successes and hug me to your family, I always feel like mine. I'm not exaggerating.