“El chiste como forma de comunicación y de enviar mensajes políticos es utilizado por los políticos más exitosos. (…)

Mesić debe en gran parte su segunda victoria presidencial a sus chistes y burlas a costa de su contrincante Jadranka Kosor. Recordamos aquella frase humorística suya cuando dijo que ya tenía miedo de abrir una lata de paté porque de ella podría saltar Suzana, el apodo burlón con que se refería a su rival Jadranka. (…)

Por supuesto, también en el mundo hay políticos que saben reírse, incluso de sí mismos. Una de las frases más conocidas es de Winston Churchill, quien comentó sobre su afición al alcohol: ‘He tomado más del alcohol que lo que el alcohol ha tomado de mí’.

En Croacia, el aforismo es una forma de humor altamente desarrollada para burlarse de los políticos y el poder. Solo mencionemos que en 2022 se publicaron en Croacia 25 libros de aforismos, ninguno con apoyo estatal.

Nuestro aforista Danko Ivšinović dijo en uno de sus aforismos que el 10% de los croatas viven como riñones en manteca, y el resto está en diálisis. Dado el creciente empobrecimiento, Croacia deberá aumentar el número de máquinas de diálisis, y ese 10% de ‘riñones en manteca’ está cayendo drásticamente con las últimas acciones de la oficina anticorrupción USKOK”. (1)

Carl Lonzhar (Dragutin Lončar) (1876-1954)

Mientras que por un andarivel de la vida continuamos reflexionando y debatiendo con respecto al humor y otros aspectos importantes de la existencia cotidiana como el precio de las bergamotas, sí es sumamente preocupante que tal personaje político cuando habla en serio hace reír o asusta.

En definitiva o casi, más abajo o arriba transitamos por senderos que nos conducen al histórico río Rubicón, sin saber qué pasará al llegar a su orilla, en la seguridad, como Julio César (100 a.C.-44 a.C.), que “los dados (la suerte) están echados (alea iacta est)”.

Al respecto, como bien apuntó Pepe Pelayo: “Además de tener la intención de hacer reír o sonreír, tengo la otra intención de hacer pensar y sentir también, con otros elementos en mi mensaje.

En otras palabras, uso el humor en el arte como medio para conseguir otra meta y en este caso no lo usé con el fin de lograr solamente la risa o la sonrisa”. (2)

UN GENIO QUE PERDURA

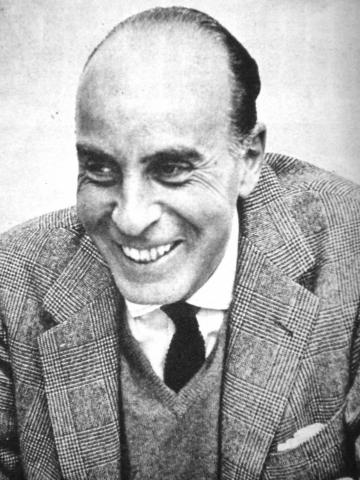

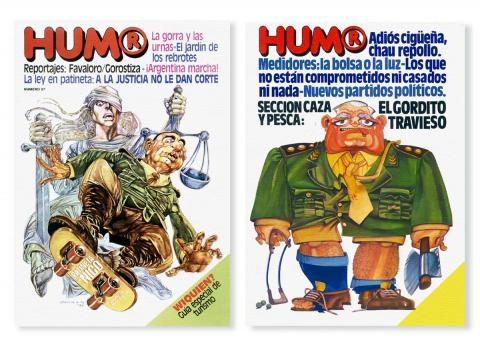

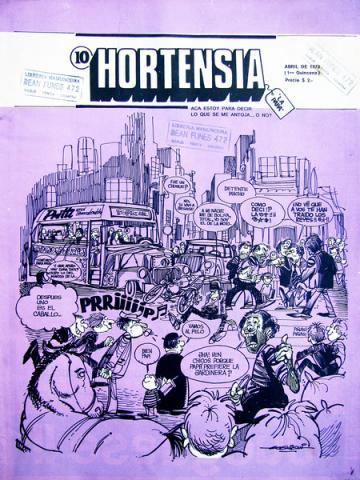

Juan Carlos Colombres (Landrú) (1923-2017) fue un destacado humorista gráfico y narrativo argentino que por sus textos y dibujos le significaron un muy amplio interés popular. Resultó económicamente exitoso en sus emprendimientos periodísticos, infrecuente en Argentina de inexplicables cierres por razones financieras: “Humor Registrado” (1978-1999), “Hortensia” (1971-1989), etcétera.

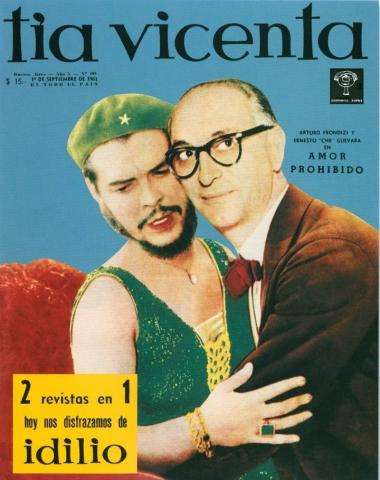

A su Tía Vicenta la publicó entre 1957 y 1966, 369 números; 1977 y 1979, 88 números semanales: 457 entregas de inteligente humor.

Todas sus tapas son magníficas lecciones de humor gráfico. Con asiduidad empleó muy divertidos fotomontajes: un árbitro de box levanta el brazo de Kennedy en señal de su triunfo electoral. (Año IV, N°17º. 12 de noviembre 1960).

El característico tamaño de la Revista la redujo notablemente (“número diminuto”) como humorada cuando el personaje de la chanza era de relativa baja estatura como el Vicepresidente (1963-1966) Carlos Humberto Perette (1915-1992).

A veces ciertos números estuvieron disfrazados de otras revistas como “La Chacra”, logrando divertidos travestismos humorísticos.

Su humor político y costumbrista fue sobre y nunca en contra; dos preposiciones bien distintas.

Fue un innovador nato que, de existir, debería ocupar uno de los capítulos principales del libro Historia Universal del Humor. En serio.

En Argentina existen más de 200 espacios públicos con el nombre de un mismo político ¿cuántos se denominan Juan Carlos Colombres?

A los siete años de edad ideó y desarrolló una publicación con sus humoradas e historietas; la distribuyó entre sus compañeros de aula; de encontrase algún ejemplar podrá ser considerado como un incunable de valor pecuniario incalculable.

Desde joven fue reconocido como un destacado humorista. Su versatilidad y constante creatividad disruptiva sustentaron su labor con profesionalismo, siempre atento a los cambios de época en la turbulenta política de Argentina.

En estas décadas devastadas del Siglo XXI todo es más aberrante; hasta los humoristas están atónitos y sobrecargados de trabajo.

Su localismo y la inmediatez de las muy divertidas páginas difícilmente puedan traducirse con eficacia y comprenderse hoy en día sin adosarles atinentes comentarios históricos.

Como pocos humoristas se destacó al unísono por sus dibujos y textos.

Fue un cabal erudito y llano en sus obras. Nunca cayó en lo chabacano ni necesitó de palabras soeces.

Colaboró con numerosas publicaciones además de las propias.

Fue un gran cultor de la sátira y la ironía.

ALGUNOS PERSONAJES

Con respecto a sus textos y dibujos, según declaraciones del autor, para la elaboración de estas creaciones caricaturescas siempre se inspiró en conocidos.

Para adentrarse en los mismos es necesaria una gran cuota de perspicacia bien alejada de una lectura lineal. Debajo del agua se encuentran los mejores chistes.

La exitosa actriz argentina Laila Roth (que la involucran las generalidades de la ley) puntualizó “Mi límite es que me cause gracia a mí y no ofender a alguien que no me interesa ofender. Se hería a mucha gente. Hay cosas de las que no se habla y no porque sea incorrecto sino porque ya no causan gracia. Un chiste sobre rubias es una pavada, por ejemplo. O los chistes sobre gordos nos hieren. Ahora tenés consecuencias si hablás de ciertas cosas y no gusta responder a gente que se enoja con tus chistes. Hay truquitos del comediante para buscar chistes que no hieran. Por ejemplo, si pienso algo que es incorrecto, por ahí lo digo pero en boca de mi tía y el chiste funciona igual y mi postura queda clara. Hay que encontrar cuándo vale la pena y cuándo no. Y tampoco hay que llorar tanto”. (3)

UNO

Su creatividad sin fin lo llevó, cada vez que lo consideró necesario, a inventar personajes atinentes como, por ejemplo, el “señor Cateura”, carnicero de barrio, que aspiraba a ser multimillonario y ascender socialmente, aparentando siempre un gran desarrollo cultural. Hoy en día existen ciertos mediocres políticos que balbucean en inglés y citan por boca de ganso pasajes históricos y literarios.

El carnicero en cuestión, de larga y tupida renegrida barba, maltrataba a su hijo Felipito pues debía aprender latín a la perfección para continuar exitosamente con el negocio del padre. Hoy en día hay niños con múltiples actividades extracurriculares por lo que terminan el día muy cansados y sin tiempo para jugar.

“Felipito, el hijo del señor Cateura estaba observando desde la azotea de la casa el paso del satélite artificial. El señor Cateura, en cuanto llegó, buscó a su hijo por toda la casa, y cuando lo encontró le pegó un furibundo puntapié en la nuca.

-¡Monstruo! ¡Canalla! ¡Miserable! -gritó el hombre, echando espuma por la boca, mientras retorcía el cuello de Felipito-. ¿Conque espiando las piernas de las vecinas?

-No, papá -se apresuró a decir el niño-. No espiaba a las vecinas. Estaba esperando que pasara el satélite artificial.

-¡Excusas! ¡Puras excusas para no estudiar! -chilló el señor Cateura, al mismo tiempo que mordía con furia una oreja de Felipito-. ¿Te crees que mirando al cielo como un papamoscas vas a disolver la Convencional? ¿Te crees que mirando el satélite vas a conseguir que caiga el decadente gobierno vasco? ¿Te crees que mirando las piernas de la vecina vas a conseguir una huelga general? ¡No, demonio! Porque una huelga general sólo la conseguirás estudiando latín, porque el latín, bruto, te enseñará a ser un buen depuestista (SIC) (deportista) y te enseñará a ser el mejor carnicero del barrio, como soy yo.

-Pero ya estudié latín, papá -se animó a opinar Felipito. Ahora estaba esperando que pasara el satélite.

-¡Qué satélite ni satélite, bestia! -rugió el señor Cateura, mientras arrastraba al niño de los pelos por toda la azotea-. Lo que tú hacías era espiar a las señoritas de enfrente. ¿Te parece bien, imbécil, que mientras tu pobre padre gasta montones de dinero en libros de latín, tú te pasas espiando a las vecinas? ¿Te parece bien, depravado, que mientras yo me sacrifico trabajando todo el día en la carnicería, tú te pasas mirando las piernas de todas las señoritas del barrio? ¡No, canalla! ¡Pundonor y decencia! ¡Rectitud y moral! ¡Austeridad y continencia! Eso es lo que necesitas, monstruo repugnante.

-¿Qué es lo que pasa? -preguntó Jezabel, la señora de Cateura, que entraba en ese momento.

-Que al degenerado de tu hijo le da por espiar a las señoritas de enfrente, en vez de estudiar latín -explicó Cateura, al mismo tiempo que daba a Felipito un feroz rodillazo en la campanilla.

-¡Castígalo por bruto! -gritó Jezabel- ¡Así aprenderá que con lo único que podrá ser un buen carnicero, es con el estudio del latín!

Y el señor Cateura, luego de golpear otra vez a su hijo, se encerró en su dormitorio y se puso a leer ávidamente el libro “La Hembra”. (4)

Cabe señalar que Landrú publicó un relato muy parecido donde el padre, autoritario y sumamente agresivo, es el Doctor Regúlez y su hijo Felipito es muy aficionado a la filatelia alejado del estudio obligatorio del Latín como lo era en toda Argentina de esa época. Adela es la complaciente esposa. (Notables Padres. La Familia del Dr Regulez. Pobre Diablo (Año 8, N° 448. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 9 de julio de 1954). (El apellido aparece a veces con tilde y otras veces no).

DOS

Rogelio, el hombre que razonaba demasiado. Clase media acomodada mediante el trabajo productivo que se dedica con empeño.

Siempre está preocupado por la inestabilidad del país y, particularmente la propia.

Políticamente conservador.

Con una gran y desproporcionada cabeza sin cabellos, siempre con un pequeño sombrero; elegante y formalmente vestido como a principios del Siglo XX.

“Rogelio, el hombre que razonaba demasiado, entró a un cine.

-Deme una platea -le dijo al boletero.

-¿En qué fila?

Rogelio automáticamente se puso pensar:

Desea saber en qué fila quiero.

En los teatros de revistas la mejor fila es la cero.

El cero a la izquierda no vale nada.

El que nada no se ahoga.

Los que se ahogan gritan ¡Socorro!

Mi prima se llama Socorro.

Socorro está de novia.

Luego, el boletero ha querido preguntarme si vengo al cine con Socorro.

-No -le dijo Rogelio-. Deme una sola platea. Socorro no puede venir conmigo al cine porque está de novia.

-¿Qué dice? -preguntó el boletero, que creía no haber oído bien.

Rogelio prosiguió con sus razonamientos.

Yo digo que Socorro está de novia.

Los trajes de novia tienen cola.

Coca-cola es una bebida.

Coca es la hermana de Socorro.

Coca no está de novia.

Por lo tanto, si Coca no está de novia, puedo venir al cine con ella.

-Tiene razón -dijo Rogelio al boletero -deme dos plateas en la fila doce.

El empleado, mirando de reojo, le dio dos entradas, y Rogelio, luego de sentarse en su platea, abrazó a una señorita que tenía a su lado.

-¡Socorro! -gritó la señorita.

-¿Socorro? -dijo Rogelio sorprendido-. Perdón. No sabía que usted era Socorro. Yo creía que usted era Coca”.

TRES

El Señor Porcel discute siempre por cualquier asunto, frecuentemente enredándose en sus propios sin sentidos:

“El señor Porcel fue a la mesa donde le tocaba votar. El presidente firmó el sobre, se lo entregó y le dijo:

-Puede pasar al cuarto oscuro.

-¿Al cuarto oscuro? -preguntó asombrado el señor Porcel- ¿Y por qué oscuro? ¿Todavía siguen los cortes de luz? Yo creí que con la anulación de las concesiones a la C.A.D.E. (5) no habría más apagones. (Humorada en cuanto a las empresas extranjeras versus nacionales y privadas o públicas).

-No -explicó el presidente de mesa, sonriendo-. Le decimos cuarto oscuro, pero en verdad está iluminado.

-¡Fraude! -gritó el señor Porcel-. Si el cuarto es oscuro, no puede estar iluminado.

-Es que se le dice oscuro por costumbre -respondió con calma el presidente. Es oscuro, pero hay luz.

-¿Así que usted para decir una cosa dice otra? -protestó el señor Porcel- ¡Es extraño! Porque entonces, según usted, si yo quiero votar por los intransigentes tengo que votar por los del pueblo. (Dos partidos políticos de la época).

-No, no -balbuceó el presidente, que comenzaba a confundirse-. Si usted quiere votar por los intransigentes, debe poner una boleta intransigente.

-Pero da la casualidad de que yo soy demócrata cristiano. Y porque a usted se le ocurra, por más presidente de mesa que sea, no voy a votar por Frondizi siendo demócrata cristiano, en un cuarto oscuro que está iluminado.

-Pero ¿qué dice? -tartamudeó el presidente-. Si me dice por quién va a votar, tengo que anular su voto.

-¿Que va a anular mi voto? -rugió el señor Porcel-. ¿Qué voto? Si yo todavía no he votado. ¿Cómo voy a votar en una mesa donde los cuartos oscuros tienen luz?

-Pero es que …

-¡Pero un demonio! -gritó el señor Porcel perdiendo la paciencia-. Ya estoy asqueado del fraude. Ustedes, los políticos, son todos iguales. Por mí que ganen los intransigentes, los del pueblo o los socialistas, que es lo mismo. Pero lo que es yo ni aunque me maten voy a votar en un cuarto oscuro iluminado. Me iré a otro lado.

Y el señor Porcel fue a otra mesa, se acercó a un fiscal con una boleta en la mano, y le dijo:

-Le cambio esta boleta demócrata cristiana que tengo repetida por dos votos en blanco”.

CUATRO

María Belén y Alejandra (dos jóvenes frívolas, de alto poder adquisitivo, clasistas, despectivas, consumistas, con argot característico). Inicios de la minifalda. Fue una serie de columnas que divirtió a muchos incluyendo a los sarcásticamente retratados, independientemente del género y el lugar de residencia.

“La página del Barrio Norte”. 1968.

|

CINCO

Tía Vicenta

Su personaje principal, que dio nombre a la Revista, sin duda, es Tía Vicenta, socialmente destacada como para figurar en la “Guía Azul”, es decir el Registro alfabético con los teléfonos y direcciones de la gente como uno. Con un buen nivel económico.

Charlatana, medio babieca y hablando por boca de ganso.

Curiosamente, aunque perteneció a un grupo social que le daba importancia a los linajes desconocemos su apellido.

Las primeras apariciones fueron en varios semanarios y quincenarios como, por ejemplo, “Vea y Lea”. La revista de los buenos lectores”. (Editorial Emilio Ramirez, Buenos Aires, 1946).

En su número inicial incluyó el humor literario del destacado Piolín de Macramé (Florencio Escardó, extraordinario médico y humorista. 1904-1992) en “Entre y Vea”. En su Editorial convocaron a “todos los sectores intelectuales y científicos, políticos, sociales, económicos, artísticos, académicos; que ellas se debatan, se presenten y se discutan todos los problemas que interesan a la comunidad y que tengan como única finalidad y función la defensa de los intereses permanentes de la Nación”. En un país profundamente dividido y dominado por una dictadura, parece una ironía. Luego arreciaron peores tormentas…

A lo largo de su extensa carrera también inventó o difundió numerosos términos que se incorporaron al lunfardo vernáculo: fitito, gordi, Villa Cariño, colorado, mersa, petitero, gorila, etcétera.

COMO POCOS

Sus humoradas críticas a parte de sus contemporáneos, habitantes de la Gran capital federal, son extraordinarias, habiendo creado figuras caricaturescas como los bienudos con sus modismos y preocupaciones limitadas a contornos encajonados en extremo egocentrismos banales: “gordi”, A la clase media la describió con toda crudeza humorística: “mediopelo” y a los “mersas” (adjetivo culturalmente despectivo).

Su perspicacia se centró en sus contemporáneos citadinos medio pelo, que querían ser pero que no les daba el piné, incluyendo a los nuevos ricos y los snobs (sin nobleza).

También: “viejo reblandecido” mote para endilgar a los que se quedaron en el tiempo.

Muy posiblemente, en la actualidad la diversidad social y el desarrollo conceptual han superado varios de los estereotipos explícitos, aunque existen otros aberrantes descalificadores por las opiniones: “mandriles”, “ratas”, “econochantas”, “ensobrados”, etcétera. La frontera entre la democracia y el autoritarismo, a veces, es muy lábil y enmarañada.

Muy particularmente, se rió del militarismo inclusive de los demócratas convertidos cuando los vientos políticos cambiaron de rumbo o ciertos negocios pasaron a otras manos.

Además aquí nos surgen dos interesantes cuestiones más: a) ¿existen límites para el humor, tanto para el emisor como para el receptor? b) el humor es parte principal de la Cultura; las modas, siempre pasajeras, son nada más que eso.

Sumamos a sus memorables “Los grandes reportajes de Landrú” (revista dominical de La Nación, Buenos Aires).

Hasta los que se reconocían se reían a escondidas; durante años sus páginas fueron guías de conversaciones.

“Tenía un humor refinado y le gustaba ser siempre el centro de la mesa. Sabía que la gente esperaba que fuera divertido y no decepcionaba. Aunque no le gustaba ir a la televisión y su cara no salía tanto en los medios de comunicación de la época, disfrutaba cuando alguien lo reconocía por la calle y lo paraban para saludarlo. Estaba orgulloso de su popularidad”, dijo a LA NACIÓN Raúl Colombres, hijo de Juan Carlos Colombres”. (7)

EN ESA ÉPOCA

Mientras tanto, la Democracia era burdamente inestable y alta la desigualdad económica y social; los empleados públicos militares siempre al acecho para salvajemente tomar las riendas del poder con algunos de sus cómplices empresarios, sindicalistas, periodistas, etcétera. La mayoría observaba atónita.

La realidad fue la charca en que abrevó el inteligente humor de Landrú, sin dibujos soeces ni insultos verbales. ¡Qué tiempos aquellos!

Lo ridículo era creíble, de ahí su gracia; a la mayoría distinta los foráneos los catalogaban erróneamente: no parecés porteño o peor: no parecés argentino.

1945. La revista “Don Fulgencio”, dirigida por Lino Palacio (Flax), le aceptó su primera contribución rentada, entrando por la puerta grande.

1946. Humorista político en la prestigiosa revista “Cacabel” (1941-1947).

1966. Desde que la revista “Tía Vicenta” comenzó a publicarse como Suplemento del matutino “El Mundo” éste pasó de vender 200.000 ejemplares a 300.000.

Siempre logró conformar un sólido equipo de colaboradores que contribuyó en mucho a la diversidad de los aportes: Carlos Garaycochea (1928-2018), Joaquín Salvador Lavado Tejón (Quino) (1932-2020), Jorge Palacio (Faruk, Trabuco, Ari, Jorge Raúl, Toto, Aníbal y Jotape.) (1926-2006), Carlos Warnes (César Bruto) (1905-1984) y, entre otros, Jorge Luis Basurto (Basurto) (1925-1992).

ADEMÁS

Luego de que al general y político Juan Domingo Perón sus compañeros militares golpistas lo derrocaron en 1955, en 1957 Landrú fue el primer guionista de Mauricio Borensztein (Tato Bores), contribuyendo en mucho al notable éxito del ciclo emitido por el Canal 7 de Buenos Aires: “Caras y morisquetas”.

Fue un autor muy prolífero, destacándose por igual como dibujante y como por sus creaciones escritas. Sus caricaturas son geniales.

A raíz que la dictadura de Juan Carlos Onganía (1914-1995) y sus cómplices le clausuraron “Tía Vicenta” inmediatamente publicó “María Belén” y “Tío Landrú”, extraordinaria y valiente humorada. Al déspota no le hizo gracia que su cara fuera animalizada en una morsa (Odobenus rosmarus), aludiendo a sus grandes y tupidos bigotes. (N° 341, Año X, 17 de julio de 1966). “Valiente de verdad era el que decía Onganía morza a un dictador. Y ponía una bota negra en la tapa. Landrú fue un enorme de verdad”. (Facundo Landívar).

Al destacado presidente (1958-1962) Arturo Frondizi (1908-1995) lo caricaturizó, en toda la extensión de la tapa a color, con la cabeza de un dromedario, en primer plano portando unos enormes antejos con marco negro. (Año VI. Marzo de 1962).

En cambio la genial caricatura del gran demócrata, el presidente (1963 1966) Arturo Umberto Illia (1900-1983) cuando fue representado como una tortuga, en país políticamente convulsionado. (Revista Todo. Buenos Aires, (10 de noviembre de 1964). “ZOOLOGÍA". (Maestro a sus alumnos, con aspecto sel Siglo XIX) Según mis últimas investigaciones, niños, la tortuga desciende del peludo”) Presidente (1916-1922 y1928-1930) Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (Hipólito Yrigoyen) (1852-1933); ambos de la Unión Cívica Radical). El mote “peludo” fue por sus frecuentes caminatas nocturnas por diversas calles de distintos barrios porteños.

Siguiendo con la costumbre de muchos humoristas, desde sus inicios empleó para identificarse varios seudónimos: “JC Colombres”, luego “JC”, adoptando en forma definitiva “Landrú” haciendo referencia explícita al múltiple estafador y asesino serial francés Henri Désiré Landru (1869-1922).

Muchas de sus humoradas gráficas incluyeron su característica segunda firma: un muy simpático gato negro.

La revista “Tía Vicenta” tuvo una tirada de 50.000 ejemplares donde gran parte de numerosos de sus avisos comerciales fueron redactados e ilustrados humorísticamente por él mismo.

De los muchos: “EN LA GRAN VÍA DEL NORTE Confitería Cambridge” (Ilustrado con un divertido anciano académico universitario inglés). (¼ de página). (Año I, N° 17. Buenos Aires, 3 de diciembre de 1957).

También, de forma destacada, incluyó siempre un humorístico Sumario inventado en tono catastrófico: “Aún quedan muchos presos políticos en Villa Devoto”. “Cómo preparar el sulfato de Laferrere”. “En la Argentina los únicos privilegiados son los gorilas”. (Reemplazó niños). (Gorilas: contrarios al peronismo). “Esa Boca es míaʼ, dijo Juan de Dios Filiberto”. “¿Puede un presidente cruza la barra del sonido”. ¡Drácula invadió Tía Vicenta!”. “Hoy, Pigmalión y dibujos”. (Año I, N° 17. Buenos Aires, 3 de diciembre de 1957).

SIGUE RECONOCIDO CABALMENTE

Con frecuencia cultivó el humor absurdo en cuanto a la descabellada realidad política que conoció y analizó a rajatabla.

Muchos de sus aportes gráficos, a primera vista, parecen dibujos infantiles lo que significan mayor ingenio y destreza.

También fue un inteligente lector como pocos políticos de su época y en la actualidad.

Sus muy abundantes textos, irónicamente graciosos, trasuntan su muy desarrollado pensamiento abstracto que impele, aún hoy en día, a seguir comprendiéndolo cabalmente con una gran cuota perspicacia alejada de visiones lineales y del nefasto pensamiento único.

Con sus tan característicos dibujos, absolutamente disruptivos, logró moldear su impronta personal por la que continúa siendo identificado a la distancia de décadas.

Fue un excelente crítico social y político, cultivando con maestría la ironía. En varias oportunidades fue censurado, incluyendo el secuestro violento de ejemplares por parte de los poderes públicos como, por ejemplo el 17 de julio de 1966.

Al respecto, en un excelente trabajo, Bettina Favero y Maylen Bolchinsky apuntaron: “La propuesta de Landrú fue innovadora para el humor gráfico nacional. Aquellos trazos limpios y minimalistas, un tipo de dibujo entre ingenuo y primitivo –que Oski, Oscar Conti, había incorporado pocos años antes–, combinado con lo absurdo, eran influencia directa de Saul Steinberg, un ilustrador rumano que contribuyó notablemente a varias generaciones de dibujantes argentinos. Inspirado en revistas de humor político europeas, como la italiana Bertoldo –que en tiempos del fascismo de Mussolini, propuso un sutil y absurdo humor político que evitó la censura– o la española La Cordoniz –que ironizaba ingeniosamente al régimen franquista–, Landrú renovó el humor y la gráfica argentina de entonces. (…)

ʽLas cuotas de papel en esa época las otorgaba o negaba el Ministerio de Comercioʼ, cuando Landrú realizó un chiste en la tapa que aludía a la CGT resultó inaceptable y les fue negada la cuota de papel’. En forma paralela a su actividad en el mundo gráfico, Colombres continuó trabajando en Tribunales. En 1953, a un año de la muerte de Eva Perón, mientras en el ámbito nacional continuaban exacerbándose las disputas políticas denunció que, tras haber obtenido un ascenso y un aumento de sueldo, recibía un monto menor al declarado. Según declaraciones de Colombres, la diferencia era destinada a la fundación ‘Eva Perón’ y tras recibir presiones para afiliarse al justicialismo, decidió pedir licencia. Unos meses después ya se había acomodado en trece revistas, de ahí en más se dedicó de lleno al humor. Ironizaba sobre aquellos tiempos: Gracias al peronismo yo me dedico al dibujo”. (8)

El trabajo aquí comentado incluye varias reproducciones de dibujos de Landrú, completando muy atinadamente la notoria labor de las autoras.

VEAMOS

“Nuestra editorial. Trampitas

Nosotros conocemos al pueblo argentino. No es que el argentino sea un pueblo malo, ni que no quiera trabajar, ni que desee ganar al máximo de dinero con el mínimo esfuerzo. Lo que sucede es que al pueblo argentino le gustan las trampitas. Trampitas para el trabajo, para los negocios, para la política, para la chacota. Trampitas para todo.

Todo el mundo busca la trampita. En un negocio determinado, se busca la trampita para desplumar a alguien y quedarse con todo el dinero. En la oficina se busca la trampita para trabajar lo menos posible y cobrar el máximo de las horas extras. En la política se busca la trampita electoral para conseguir votos rivales y ganar las elecciones. En la chacota se busca la trampita para bailar y divertirse como loco con una mulata sin que nadie se entere. En la televisión se busca alguna trampita para sin ser publicitario tener varios espacios en las mejores horas, vender esos espacios a alguna firma comercial y buscar alguna otra trampita para intercalar en ese mismo espacio vendido publicidades de otros productos. En la Aduana se busca alguna trampita para poder entrar al país, sin pagar recargo alguno, 510 automóviles, 854 máquinas de escribir o 678 aparatos de televisión. Y así.

Por eso es que los argentinos son tan reacios y tan enemigos de acatar la ley. Si sale una ley de tránsito, ya se encontrará una trampita para no cumplirla. Si sale una ley de réditos, ya se buscará una trampita para eludirla. Y si sale una ley de juegos, ya se encontrará una trampita para burlarla.

Nosotros ignoramos si las autoridades conocen este juego argentino de las trampitas. Ya sea en el más importante y complicado negocio, o en la más insignificante actividad, siempre existe la trampita. En una importante solicitud de préstamo al extranjero, se encontrará la trampita para que se nos preste cuanto antes el dinero y ganarnos el 10% de la comisión. Y en esa actividad menos importante, como la grabación de un disco, se encontrará la trampita (vos de negro, un hombre que canta con voz de mujer, un instrumento extraño o un conjunto musical con nombre exótico), para imponer determinada música.

Por eso nosotros sugerimos al gobierno, que tan distanciado se encuentra de nuestro pueblo, que para acercarse a él deberá agregar en las leyes, decretos u ordenanzas, algunos artículo extras aplicando las trampitas para burlarlos. Por ejemplo: si se promulga una ley prohibiendo fijar carteles en las paredes, la trampita estará en que se podrán pegar carteles pagando luego a la Municipalidad una multa de cinco centavos por cada mil carteles. O si por ley se prohíbe traer autos del sur del paralelo 42 (zona franca), la trampita estará en que al llegar a Buenos Aires se podrá cambiar la patente por una de la Capital Federal, en el garaje más cercano. O si por un artículo del Código Civil se prohíben los duelos en la Argentina, la trampita estará en que el gobierno ponga a disposición de los caballeros que van a batirse un moderno avión de Aerolíneas, para que los traslade a la ciudad de Colonia, lugar donde se realizará el duelo, si hay plafond.

Con estas explicaciones de burlas a la ley, el gobierno se acercará más al pueblo y podrá esperar confiado el resultado de las próximas elecciones de marzo. Salvo que Frondizi tenga otra trampita como la de hace dos años y obtenga para su partido una aplastante victoria”. (9)

MERECIDO HOMENAJE

“Puchunguita es un encanto/ mi puchunga es un primor/ las caderas de mi negra/ miden 122ʼ. Parte de la cumbia de Mike Laure, interpretada con cadencia por Juan Carlos Colombres, Landrú, fue la sorpresa de la presentación de ¡El que no se ríe es un maleducado!, la compilación de toda su obra.

El público que se acercó ayer al Salón Dorado de la Legislatura porteña sonrió y aplaudió la humorada de Landrú, que prefirió protagonizar un video casero para participar del homenaje que sus colegas, sus simpatizantes y los diputados de la ciudad ofrecieron ayer al destacado humorista.

ʽNo estoy para emociones violentasʼ, se había disculpado Landrú ante Horacio del Prado, el compilador del libro, quien contó la anécdota y dejó en suspenso el saludo del maestro hacia su público.

Fue divertido escucharlo cantar y reír ʽA puchunga la invitaron/ al velorio de Ramón/ el muerto vio sus caderas/ de pronto resucitó una cumbiaʼ, en el intento de restarle solemnidad al reconocimiento de toda su carrera.

¡El que no se ríe es un maleducado! es una amplísima recopilación de 10 capítulos y 462 páginas, editada por Alpha Text, en la que Horacio del Prado, hijo de Calé, otro historietista legendario, trabajó durante tres años, y que cuenta con prólogos de colegas, historiadores, especialistas en lengua castellana y hasta de la actriz Norma Aleandro, con la que Landrú compartió durante un tiempo un programa de radio.

Ciudadano ilustre de la ciudad desde 2003. (...)

Antes y después de Tía Vicenta, su genio tuvo lugar en las páginas de Vea y Lea, Avivato, Pobre Diablo, Rico Tipo, Patoruzú, Sucedió con la Farra, Dinamita, Gente de Cine, Loco Lindo, Leoplan, Gente y la Actualidad, Somos, Mercado y los diarios El Mundo y Clarín. En 1971, la Universidad de Columbia le otorgó el destacado premio María Moors Cabot, el más antiguo reconocimiento internacional en periodismo.

Entre sus personajes más destacados se recuerdan la Tía Vicenta, Rogelio ʽel hombre que razonaba demasiadoʼ, al Doctor Chantapufi y el señor Porcel.

Landrú ha satirizado la política argentina desde el primer mandato de Juan Domingo Perón en 1945 hasta la gestión del ex presidente Néstor Kirchner. ʽEl humor político de Landrú es una lima sorda: va poniendo en su lugar los ridículosʼ, resumió el presidente de la Academia Nacional de Educación, Pedro Luis Barcia, que, en su habitual tono humorístico, recordó algunos de los chistes más absurdos de Landrú.

ʽLa sumatoria del trabajo de Juan Carlos es monumental. Su humor no envejece, sino que es una gran calesitaʼ, sostuvo su colega Hermenegildo Sábat, actual presidente de la Academia Nacional de Periodismo, quien repasó sus inicios en el periodismo gráfico junto a Landrú.

El periodista radial Rolando Hanglin se definió como un ʽgran fanático de Landrú de toda la vida" y desgranó recuerdos y anécdotas personales. "Era el absurdo llevado al paroxismoʼ, planteó Hanglin al referirse al creador de publicaciones fundacionales como la revista Tía Vicenta.

ʽHemos trabajado juntos. Es el genio más grande de nuestro pequeño gremio de periodistas humoristas. Nunca agravió. Nunca agredió. Es un gran observador de las tendencias y de los tipos sociales. Siempre pescaba con precisión y con fuerza todos los tipos humanos de Buenos Aires y también sus conceptos y sus ideasʼ, añadió. En primera fila, buena parte de la familia de Landrú seguía con atención cada comentario. Uno de sus hijos, Raúl, asistió acompañado por buena parte de sus hijos y de sus nietos.

Apenas un poco más atrás, se repartían muchos amigos y colegas de la vida del humorista, como Miguel Brascó, Juan Carlos Saravia, José Claudio Escribano, Antonio Requeni, Norberto Firpo, Eduardo Meléndez, Luis Grosman y Daniel Balmaceda.

Casi todos tenían comentarios para hacer en voz baja y con una sonrisa nostálgica sobre los personajes de historieta que adornaban el pequeño estrado: el Señor Porcel, el Señor Cateura, Rogelio, María Belén, Tía Vicenta, Jacinto W el Reblan, Sir Jonás el Executive, el Gato Clase A, Mirna Delma.

El Diputado porteño por el Pro y vicepresidente de Boca Juniors, Oscar Moscariello ofició de anfitrión de la ceremonia en el Salón Dorado de la Legislatura y recordó el impacto que había causado en su familia la clausura de la revista Tía Vicenta, dispuesta por el gobierno militar de 1966.

ʽComo humorista político, hoy Landrú pondría una cuota de humor. Hacía sociología humorísticaʼ, destacó Moscariello, al calificar el ʽhumor político como un editorial de una profundidad enormeˮ. (10)

PARA PENSAR

¿Por qué reímos cuando nos reímos? Las razones pueden ser muchas y variadas como, por caso, cuando escuchamos una expresión infantil muy madura para la edad, observamos una situación disparatada, estamos viendo una película protagonizada por Cantinflas, tomamos contacto con una engañosa noticia paga personalista, cagatinta, y triunfalista, etcétera.

También cuando leemos un antiguo texto que podría haberse escrito ayer por su plena vigencia.

La constatación que poco o nada ha cambiado, ni se modificará en el futuro, es un buen disparador humorístico que amortigua, por ejemplo, la desazón experimentada.

Al escuchar como verdad revelada que todo pasado fue mejor rápidamente lo relacionamos con las falsas promesas electorales que venden futuros venturosos.

La burda mentira puesta en evidencia muchas veces genera, al menos, una sonrisa además de indignación.

Al ser palpable el acostumbramiento individual y social a convivir con pequeñas mentiritas cotidianas, además de preanunciar una escalada en tal sentido, puede intervenir algún proceso humorístico como cuando, con la puerta cerrada, hacemos morisquetas frente a un espejo y nos reconocemos sin tapujos.

NOTAS Y REFERENCIAS

1) Lončar, Dragutin. El humor desde Croacia | La risa en la política. Boletín Humor Sapiens. Chile. Julio de 2025.

2) Pelayo, Pepe. Teoría Humor Sapiens. Lo cómico, el humor y el chiste. Humor Sapiens Ediciones. Página 102. Chile. Agosto de 2022.

3) Roth, Laila. Laila Roth, la estudiante de Estadística que apostó por el humor y hoy se luce en los escenarios y en la televisión. Entrevista de Liliana Podestá. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 3 de octubre de 2025.

4) Personajes de Landrú.

5) Controvertida empresa de distribución domiciliaria de energía eléctrica en Buenos Aires y alrededores. (1921 y 1961).

6) Guiño humorístico a la exitosa película estadounidense Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, producida y dirigida por Stanley Kramer (1967). Trata sobre los prejuicios raciales.

7) Blanc, Natalia. Landrú: el primer influencer del humor gráfico argentino. Fundación Landrú. 16 de febrero de 2023.

8) Favero, Bettina y Bolchinsky, Maylen. Juan Carlos Colombres: “Y usted, ¿por qué me mira?”. Estudios de Teoría Literaria. Revista digital: artes, letras y humanidades. Volumen 9, N° 18. Páginas 4 y 5. Mar del Plata, Provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

9) Tía Vicenta. Trampitas. Revista Tía Vicenta. Año IV, número 129. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 26 de enero de 1960. Marzo de 2020.

10) Polack, María Elena. Landrú: de Perón a Kirchner, 60 años de humor político y absurdo. La Nación. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 6 de marzo de 2014.

Juan Carlos Colombres (Landrú) (1923–2017)

Personaje: "señor Cateura"

Landru, genius and figure

By Alejandro Rojo Vivot

“The joke as a form of communication and of conveying political messages is used by the most successful politicians. (…)

Mesić owes much of his second presidential victory to his jokes and mockery at the expense of his opponent Jadranka Kosor. We recall that humorous remark of his when he said he was already afraid to open a can of pâté because Suzana might jump out — the mocking nickname he used to refer to his rival Jadranka. (…)

Of course, in the world there are also politicians who know how to laugh, even at themselves. One of the best-known phrases is by Winston Churchill, who once commented on his fondness for alcohol: ‘I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.’

In Croatia, the aphorism is a highly developed form of humor used to make fun of politicians and those in power. Let us simply mention that in 2022, twenty-five books of aphorisms were published in Croatia, none with state support.

Our aphorist Danko Ivšinović said in one of his aphorisms that 10% of Croatians live like kidneys in butter, and the rest are on dialysis. Given the growing impoverishment, Croatia will have to increase the number of dialysis machines, and that 10% of ‘kidneys in butter’ is dropping drastically with the latest actions of the anti-corruption office USKOK.” (1)

Carl Lonzhar (Dragutin Lončar) (1876–1954)

While on one track of life we continue reflecting and debating about humor and other important aspects of daily existence—such as the price of bergamots—it is deeply troubling that such a political figure, when speaking seriously, either makes people laugh or frightens them.

Ultimately—or almost—further down or further up we travel along paths that lead us to the historic Rubicon river, without knowing what will happen once we reach its shore, certain, like Julius Caesar (100 BC–44 BC), that “the die is cast” (“alea iacta est”).

In this regard, as Pepe Pelayo rightly pointed out: “In addition to having the intention of making people laugh or smile, I also have the intention of making them think and feel something as well, with other elements in my message.

In other words, I use humor in art as a means to achieve another goal, and in this case I did not use it with the aim of achieving only laughter or a smile.” (2)

A GENIUS WHO ENDURES

Juan Carlos Colombres (Landrú) (1923–2017) was an outstanding Argentine graphic and narrative humorist whose texts and drawings earned him wide popular interest. He was economically successful in his journalistic ventures—unusual in Argentina, where inexplicable closures for financial reasons are common—such as “Humor Registrado” (1978–1999), “Hortensia” (1971–1989), etc.

He published his Tía Vicenta between 1957 and 1966 with 369 issues; and in 1977 and 1979, 88 weekly issues: a total of 457 installments of intelligent humor.

All his covers are magnificent lessons in graphic humor. He frequently used very amusing photomontages: for example, a boxing referee raising Kennedy’s arm in signal of his electoral victory (Year IV, No. 17, November 12, 1960).

He drastically reduced the characteristic size of the magazine (“miniature issue”) as a joke when the subject of the humor was of relatively short stature, such as Vice President (1963–1966) Carlos Humberto Perette (1915–1992).

Sometimes certain issues were disguised as other magazines such as La Chacra, achieving amusing humorous transformations.

His political and costumbrista humor was about people and events, never against them—two very different prepositions.

He was a born innovator who, if such a book existed, should occupy one of the main chapters of a Universal History of Humor. Seriously.

In Argentina there are more than 200 public spaces named after the same politician; how many bear the name Juan Carlos Colombres?

At the age of seven he conceived and produced a publication with his jokes and comic strips; he distributed it among his classmates. Should a copy be found, it could be considered an incunable of incalculable monetary value.

From a young age he was recognized as an outstanding humorist. His versatility and constant disruptive creativity sustained his work with professionalism, always attentive to the changes of the times in Argentina’s turbulent political life.

In these devastated decades of the 21st century everything is more aberrant; even humorists are astonished and overloaded with work.

His localism and the immediacy of his very amusing pages make them difficult to translate effectively and hard to understand today without adding pertinent historical commentary.

Like few humorists, he excelled simultaneously in both drawings and texts.

He was scholarly and accessible in his works. He never stooped to vulgarity or relied on obscene language.

He contributed to numerous publications in addition to his own.

He was a great cultivator of satire and irony.

SOME CHARACTERS

Regarding his texts and drawings, according to the author’s statements, for the creation of these caricatured characters he always found inspiration in well-known figures.

To fully delve into them, a great deal of perceptiveness is needed—far removed from a linear reading. Under the surface lie the best jokes.

The successful Argentine actress Laila Roth (involved by the generalities of the law) pointed out: “My limit is that it must make me laugh and not offend someone I have no interest in offending. A lot of people used to get hurt. There are things we don’t talk about, not because they’re incorrect, but because they’re no longer funny. A joke about blondes is silly, for example. Or jokes about fat people hurt us. Now there are consequences if you talk about certain things, and I don’t like dealing with people who get angry at your jokes. There are comedians’ tricks to find jokes that don’t hurt. For example, if I think of something incorrect, maybe I’ll say it but put it in my aunt’s mouth, and the joke still works and my stance is clear. You have to find out when it’s worth it and when it’s not. And you shouldn’t whine so much either.” (3)

ONE

His endless creativity led him, whenever he considered it necessary, to invent relevant characters such as “Mr. Cateura,” a neighborhood butcher who aspired to become a multimillionaire and to rise socially, always pretending to have great cultural sophistication. Today there are mediocre politicians who mumble in English and parrot historical and literary passages.

The butcher in question, with a long, thick, jet-black beard, mistreated his son Felipito because he had to learn Latin perfectly in order to succeed in his father’s business. Today many children have multiple extracurricular activities, leaving them exhausted and without time to play.

(Here follows the translated story — fully preserved in tone and humor):

“Felipito, the son of Mr. Cateura, was watching the artificial satellite pass from the rooftop of their house. When Mr. Cateura arrived, he looked all over the house for his son, and when he found him, he gave him a furious kick to the back of the neck.

‘Monster! Scoundrel! Miserable!’ shouted the man, foaming at the mouth while twisting Felipito’s neck. ‘So you were spying on the neighbors’ legs?

‘No, Dad,’ the boy rushed to say. ‘I wasn’t spying on the neighbors. I was waiting for the artificial satellite to pass.’

‘Excuses! Pure excuses so you don’t study!’ shrieked Mr. Cateura as he angrily bit Felipito’s ear. ‘Do you think that by staring at the sky like a simpleton you’re going to dissolve the Constitutional Assembly? Do you think that by watching the satellite you’re going to bring down the decadent Basque government? Do you think that by looking at the neighbor’s legs you’re going to cause a general strike? No, devil! Because you’ll only achieve a general strike by studying Latin, because Latin, you brute, will teach you to be a good depuestista (sic) (sportsman), and it will teach you to be the best butcher in the neighborhood, like I am.’

‘But I already studied Latin, Dad,’ Felipito dared to say. ‘Now I was waiting for the satellite to pass.’

‘What satellite, you beast?!’ roared Mr. Cateura, dragging the boy by the hair across the rooftop. ‘What you were doing was spying on the young ladies across the street. Do you think it’s right, you idiot, that while your poor father spends piles of money on Latin books, you spend your time spying on the neighbors? Do you think it’s right, you degenerate, that while I sacrifice myself working all day in the butcher shop, you spend your time staring at all the girls’ legs in the neighborhood? No, scoundrel! Honor and decency! Rectitude and morality! Austerity and continence! That’s what you need, you repugnant monster.’

‘What is going on?’ asked Jezabel, Mr. Cateura’s wife, who entered at that moment.

‘This degenerate of your son is spying on the girls across the street instead of studying Latin,’ explained Cateura while giving Felipito a vicious knee to the throat.

‘Punish him for being stupid!’ shouted Jezabel. ‘That’s how he’ll learn that the only way he can become a good butcher is by studying Latin!’

And after hitting his son once more, Mr. Cateura shut himself in his bedroom and eagerly began reading the book The Female.” (4)

(It is worth noting that Landrú published a very similar story in which the authoritarian and highly aggressive father is Doctor Regúlez, and his son Felipito is an avid stamp collector, neglecting the obligatory study of Latin, as was the case throughout Argentina at the time. Adela is the complacent wife. Notable Fathers. The Family of Dr. Regulez. Pobre Diablo, Year 8, No. 448, Buenos Aires, Argentina, July 9, 1954. The surname appears sometimes with an accent and sometimes without.)

TWO

Rogelio, the man who reasoned too much. A comfortable middle-class man thanks to productive work, dedicated and diligent.

He is always worried about the instability of the country and particularly about his own.

Politically conservative.

With a large, disproportionate bald head, always wearing a small hat; elegant and formally dressed, as in the early 20th century.

(Story translated in full):

“Rogelio, the man who reasoned too much, entered a cinema.

‘A seat in the stalls, please,’ he said to the ticket seller.

‘In which row?’

Rogelio automatically began to think:

He wants to know which row I want.

In revue theaters the best row is row zero.

Zero on the left has no value.

Those who swim don’t drown.

Those who drown shout ‘Help!’

My cousin’s name is Socorro (Help).

Socorro has a boyfriend.

Therefore, the ticket seller wanted to ask me whether I am coming to the cinema with Socorro.

‘No,’ said Rogelio. ‘Give me just one seat. Socorro cannot come with me to the cinema because she has a boyfriend.’

‘What did you say?’ asked the ticket seller, who thought he had misheard.

Rogelio continued reasoning.

I say that Socorro has a boyfriend.

Wedding dresses have a train.

Coca-Cola is a drink.

Coca is Socorro’s sister.

Coca does not have a boyfriend.

Therefore, if Coca does not have a boyfriend, I can come to the cinema with her.

‘You’re right,’ said Rogelio to the ticket seller. ‘Give me two seats in row twelve.’

The employee, glancing sideways, gave him the two tickets, and Rogelio, after sitting down, hugged a young lady next to him.

‘Help!’ the young lady screamed.

‘Socorro?’ said Rogelio, surprised. ‘Forgive me. I didn’t know you were Socorro. I thought you were Coca.’”

THREE

Mr. Porcel always argues about anything, often getting tangled up in his own nonsense:

“Mr. Porcel went to the table where he was to vote. The president of the table signed the envelope, handed it to him and said:

‘You may go into the voting booth.’

‘Into the dark booth?’ asked Mr. Porcel in astonishment. ‘Why dark? Are the power outages still going on? I thought that with the cancellation of concessions to C.A.D.E. (5) there wouldn’t be any more blackouts.’ (A joke referring to foreign vs. national companies, private or public.)

‘No,’ explained the president of the table, smiling. ‘We call it “dark booth,” but in fact it’s lit.’

‘Fraud!’ shouted Mr. Porcel. ‘If the booth is dark, it can’t be lit.’

‘It’s just called dark out of habit,’ replied the president calmly. ‘It’s dark, but there’s light.’

‘So you say one thing to mean another?’ protested Mr. Porcel. ‘Strange! Because then, according to you, if I want to vote for the Intransigents I have to vote for the People’s Party.’ (Two political parties of that era.)

‘No, no,’ stammered the president, beginning to get confused. ‘If you want to vote for the Intransigents, you have to put an Intransigent ballot.’

‘But as it happens, I’m a Christian Democrat. And just because you say so, even if you’re the president of the table, I’m not going to vote for Frondizi when I’m a Christian Democrat, in a dark booth that’s lit.’

‘What are you talking about?’ stuttered the president. ‘If you tell me who you’re voting for, I have to void your vote.’

‘You’re going to void my vote?’ roared Mr. Porcel. ‘What vote? I haven’t voted yet! How am I supposed to vote at a table where the dark booths have light?’

‘But it’s just that…’

‘To hell with you!’ yelled Mr. Porcel, losing patience. ‘I’m fed up with fraud. You politicians are all the same. For all I care, let the Intransigents win, or the People’s Party, or the Socialists—it’s all the same. But me? Not even if they kill me will I vote in a lit dark booth. I’ll go somewhere else.’

And Mr. Porcel went to another table, approached an election monitor with a ballot in his hand and said:

‘I’ll trade you this Christian Democrat ballot—which I have a duplicate of—for two blank votes.’”

FOUR

María Belén and Alejandra (two frivolous young women, wealthy, snobbish, scornful, consumerist, with characteristic slang).

Beginning of the miniskirt era. It was a series of columns that entertained many—including those sarcastically portrayed—regardless of gender or place of residence.

“Northside Page.” 1968.

MARÍA BELÉN AND ALEJANDRA

“What’s wrong, honey? You haven’t gone out at night for ages, and all that.”

“I’m exhausted. After the opening dance at En lo de Hansen I was dead, dead, dead.”

“Was it that much, sweetie?”

“For sure. It lasted four nights.”

“I don’t believe you, honey!”

“Believe me, it’s true. It was divine. A kilo, as poor people say.”

“And what’s En lo de Hansen, honey?”

“You’re so out of touch, sweetie! It’s a classy boîte that just opened in Ramos Mejía, two blocks from the station. It’s set in an old house, decorated like the turn of the century, with little lanterns, colorful cherubs, tall wicker armchairs, and the bar is a colonial-style iron balcony and all that.”

“How fun! I’m going to call Marce, María Pía, Tera and Morita right now so we can go with a few guys.”

“If I were you, I wouldn’t tell Morita.”

“Why not, darling?”

“Well, you know ever since Morita’s parents went broke, they belong to the V.A.M.”

“The V.A.M.? What’s that, honey?”

“The V.A.M. are the fallen from grace.”

“How funny! And what does it matter if Morita’s fallen from grace? Money doesn’t matter, babe.”

“Yes, but the V.A.M. risk mersalizing themselves. They start going out with the G.C.E. and next thing you know, they get infected. Did you know Morita’s dating a parvenu?”

“I don’t believe it! Who, honey?”

“An immigrant. A little Italian guy.”

“An industrialist?”

“For sure.”

“We’re doomed! He must be part of the New Argentina generation and all that.”

“You guessed right, honey.”

“The New Argentina totally grosses me out, it grosses me out, it grosses me out. They’re all parvenus, nouveau riche, upstarts, new-wave industrialists and all that.”

“And the worst part is how they speak. Morita’s boyfriend—some Enzo something—says acneso instead of anexo.”

“How dull! I bet when he blows his nose he turns his face away and says ‘excuse me.’”

“For sure. And he speaks in diminutives.”

“I bet he loves talking about his surgeries and all that.”

“It’s better if you don’t invite Morita at all. Otherwise she’ll come with Enzo and ruin everything.”

“How gross!”

“That’s why we’ll invite Mirna Delma. Remember she’s been trying to demersalize herself ever since she broke up with Aldo Rubén.”

“Okay. Call her, honey.”

“For sure… Calling.”

‘Hello! Residence of Mirna Delma. Who is on the opposite side of my telephone apparatus?’

‘Hi, Mirnita. It’s María Belén. How are you, babe? Want to come tomorrow and have a blast at a new boîte?’

‘Impossible, descendant of my uncles. The truth is, tomorrow I have to go from the beauty institute because my nasal appendix is covered in gentlemen of color, and I fear I won’t be presentable in the evening. Do you understand what I mean?’

‘For sure, Mirnita. Bye.’

‘What did that witch say?’

‘I have no idea. She said she couldn’t go out because her nose had “gentlemen of color” and all that. Nothing to do with anything!’

‘How funny! She meant she had blackheads.’

‘What poor people! Anyway, how about going to the movies? We could watch Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.'

‘Don’t be vulgar, honey!’

‘Sorry. I meant Guess Who’s Coming to Eat.'

“That’s better. Sounds more like Arroyo and all that.” (An upscale street, symbol of the area.)

“How lovely!”

“For sure. How lovely!”

(Tito de Morón. Magic Ruins. Chronicles of the Last Century.)

FIVE

Aunt Vicenta

Her main character, who gave the magazine its name, was undoubtedly Aunt Vicenta, socially prominent enough to appear in the “Blue Guide,” that is, the alphabetical registry of the phone numbers and addresses of “people like us.” She had a good economic standing.

A chatterbox, a bit silly, and always speaking secondhand gossip.

Curiously, though she belonged to a social group that valued lineage, her last name is unknown.

Her first appearances were in various weekly and biweekly magazines, such as Vea y Lea. “The Magazine for Good Readers.” (Editorial Emilio Ramírez, Buenos Aires, 1946).

Its inaugural issue featured the literary humor of the renowned Piolín de Macramé (Florencio Escardó, an extraordinary physician and humorist, 1904–1992) in Entre y Vea.

The editorial called upon “all intellectual and scientific, political, social, economic, artistic and academic sectors; that they debate, present and discuss all issues of interest to the community, with the sole purpose of defending the permanent interests of the Nation.”

In a deeply divided country under a dictatorship, this sounds like irony. Worse storms followed…

Throughout his extensive career he also invented or popularized numerous terms that entered the local lunfardo: fitito, gordi, Villa Cariño, colorado, mersa, petitero, gorila, and so on.

LIKE FEW OTHERS

His critical humor about his contemporaries, residents of the great federal capital, is extraordinary, having created caricature figures—such as the “bienudos” with their slang and worries limited to narrow circles, boxed into extreme, banal egocentrism: “gordi.” He described the middle class with harsh humor: “mediopelo” and the “mersas” (a culturally derogatory adjective).

His insight focused on his contemporaries, the “mediopelo” city dwellers, who aspired to be something more but lacked the necessary “piné,” including nouveau riche and snobs (without nobility).

Also: “viejo reblandecido,” a label for those stuck in time.

Nowadays, social diversity and conceptual development have surpassed many explicit stereotypes, though other aberrant disqualifiers persist for opinions, such as: “mandriles,” “ratas,” “econochantas,” “ensobrados,” etc. The frontier between democracy and authoritarianism is sometimes very fragile and tangled.

He particularly mocked militarism, even among democrats turned opportunists when political winds shifted, or certain businesses changed hands.

Here two further intriguing questions arise:

a) Are there limits to humor, for both the sender and the recipient?

b) Is humor a mainstay of Culture; trends are always fleeting, and that’s all they are.

Adding his memorable “Los grandes reportajes de Landrú” (“Landrú’s Greatest Interviews”) in the Sunday edition of La Nación, Buenos Aires.

Even those who recognized themselves laughed discreetly; for years his pages served as guides to conversations.

“He had refined humor and liked being at the center of the table. He knew people expected him to be entertaining, and he never disappointed. Although he didn’t enjoy being on television, and his face was not often seen in media, he enjoyed it when someone recognized him on the street and stopped to greet him. He was proud of his popularity,” Raúl Colombres, son of Juan Carlos Colombres, told La Nación.

IN THAT ERA

At the time, democracy was brutally unstable, and economic and social inequality was rampant; public-sector and military employees waited to seize power in collusion with businessmen, union leaders, journalists, and the like. The majority looked on in amazement.

Reality was the swamp in which Landrú’s clever humor thrived, without vulgar drawings or verbal insults. What times those were!

The ridiculous was credible, hence the grace; foreigners often mischaracterized most people: “You don’t seem porteño,” or worse, “You don’t seem Argentinian.”

The magazine “Don Fulgencio,” directed by Lino Palacio (Flax), accepted his first paid contribution, welcoming him in grand fashion.

Political humorist in the prestigious magazine “Cacabel” (1941–1947).

Since the magazine “Tía Vicenta” began publication as a supplement of the newspaper “El Mundo,” circulation increased from 200,000 to 300,000 copies.

He always managed to assemble a solid team of contributors who added much to the diversity of material: Carlos Garaycochea (1928–2018), Joaquín Salvador Lavado Tejón (Quino) (1932–2020), Jorge Palacio (Faruk, Trabuco, Ari, Jorge Raúl, Toto, Aníbal and Jotape) (1926–2006), Carlos Warnes (César Bruto) (1905–1984), and Jorge Luis Basurto (Basurto) (1925–1992), among others.

ADDITIONALLY

After General and politician Juan Domingo Perón was overthrown by his fellow coup-plotting military men in 1955, in 1957 Landrú became the first scriptwriter for Mauricio Borensztein (Tato Bores), contributing greatly to the notable success of the cycle broadcast by Canal 7 in Buenos Aires: “Caras y morisquetas.”

He was a prolific author, standing out equally as an illustrator and writer. His caricatures are brilliant.

After the dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía (1914–1995) and his accomplices shut down “Tía Vicenta,” he immediately published “María Belén” and “Tío Landrú”—extraordinary and courageous humor. The despot did not relish having his face depicted as a walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), alluding to his thick moustache (No. 341, Year X, July 17, 1966). “A truly brave person was one who called Onganía a walrus to a dictator. And put a black boot on the cover. Landrú was truly great.” (Facundo Landívar).

He caricatured the prominent president (1958–1962) Arturo Frondizi (1908–1995) across the full color cover as a dromedary, foregrounded with enormous black-rimmed glasses (Year VI. March 1962).

Conversely, the brilliant caricature of the great democrat, president Arturo Umberto Illia (1963–1966, 1900–1983), was depicted as a turtle in a politically turbulent country (Revista Todo, Buenos Aires, November 10, 1964). “ZOOLOGY. (A teacher to his students, looking nineteenth century): According to my latest research, children, the turtle descends from the armadillo.” President Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (1916–1922 and 1928–1930) (1852–1933); both from the Unión Cívica Radical. The nickname “peludo” was due to frequent nighttime walks through various Buenos Aires neighborhoods.

Following the custom of many humorists, since his beginnings he used several pseudonyms: “JC Colombres,” then “JC,” finally adopting “Landrú”—an explicit reference to the multiple fraudster and French serial killer Henri Désiré Landru (1869–1922).

Many of his graphic jokes included his distinctive second signature: a very charming black cat.

“Tía Vicenta” had a print run of 50,000 copies; many commercial ads were humorously written and illustrated by him personally.

Of the many: “ON THE GREAT NORTHERN BOULEVARD Cambridge Confectionery” (Illustrated with a witty elderly English academic). (¼ page). (Year I, No. 17. Buenos Aires, December 3, 1957).

He also notably included a humorous mock Summary in a catastrophic tone: “There are still many political prisoners in Villa Devoto.” “How to prepare Laferrere Sulphate.” “In Argentina the only privileged people are the ‘gorillas’” (a Peronism opponent). “That mouth is mine, said Juan de Dios Filiberto.” “Can a president break the sound barrier?” “Dracula invaded Tía Vicenta!” “Today, Pygmalion and cartoons.” (Year I, No. 17. Buenos Aires, December 3, 1957).

STILL FULLY RECOGNIZED

He frequently cultivated absurd humor in response to the outlandish political reality he knew and scrutinized rigorously.

Many of his graphic works, at first glance, seem like childish drawings, which reflect greater wit and skill.

He was also an astute reader, like few politicians of his era and today.

His abundant texts, ironically clever, reveal his highly developed abstract thinking, urging us—even today—to try understanding him fully, far from linear views and the disastrous single-minded thinking.

His highly characteristic drawings, absolutely disruptive, enabled him to shape a personal stamp by which he continues to be identified across decades.

He was an excellent social and political critic, masterfully cultivating irony. He was censored several times, including the violent seizure of copies by public authorities, for example on July 17, 1966.

On this point, in an excellent work, Bettina Favero and Maylen Bolchinsky noted: “Landrú’s proposal was innovative for national graphic humor. Those clean, minimalist strokes; a style somewhere between naïve and primitive—which Oski, Oscar Conti, had incorporated a few years earlier—combined with the absurd, were a direct influence from Saul Steinberg, a Romanian illustrator who contributed notably to several generations of Argentine cartoonists. Inspired by European political humor magazines, like Italy’s Bertoldo (which, during Mussolini’s fascism, proposed subtle and absurd political humor that avoided censorship) or Spain’s La Cordoniz (which ingeniously satirized Franco’s regime), Landrú renewed Argentinian humor and graphics of the time.

‘Paper quotas in those days were granted or denied by the Ministry of Commerce. When Landrú made a joke on the cover alluding to the CGT, it proved unacceptable and they were denied a paper quota.’ In parallel with his activity in graphic media, Colombres continued working in the Courts. In 1953, a year after Eva Perón’s death, while political disputes continued aggressively nationwide, he reported that after a promotion and salary increase, he received less than the declared sum. According to Colombres, the difference was allocated to the ‘Eva Perón Foundation’ and, after being pressured to join the Peronist movement, he requested a leave of absence. A few months later, he was already contributing to thirteen magazines, dedicating himself fully to humor thereafter. He joked about those times: ‘Thanks to Peronism, I devote myself to drawing.’”

The work discussed here includes numerous reproductions of Landrú’s drawings, very aptly illustrating the authors’ renowned work.

LET’S SEE

“Our editorial. Little tricks

We know the Argentine people. It’s not that Argentines are a bad people, nor that they don’t want to work, nor that they aspire to earn the most money with the least effort. The fact is, Argentines like tricks—little tricks for work, for business, for politics, for jokes. Tricks for everything.

Everyone looks for tricks. In a particular business, the trick is to fleece someone and keep all the money. In the office, the trick is to work as little as possible but collect the maximum in overtime pay. In politics, the trick is an electoral ploy to win rival votes and elections. In joking, the trick is to dance and have fun like crazy with a mulata without anyone noticing. On TV, the trick is to have several slots in prime time without being an advertiser, sell those slots to a company, and use another trick to put ads for other products in that same slot. At customs, the trick is to bring in the country, with no extra charge, 510 cars, 854 typewriters, or 678 televisions.

That’s why Argentines are so reluctant and hostile to obeying laws. If a traffic law is passed, a trick will be found to avoid obeying it. If an income law is enacted, a trick will be found to elude it. If a games law is passed, a trick will be found to dodge it.

We don’t know if the authorities know this Argentine game of tricks. Whether in the most important and complicated businesses or the most insignificant activities, there’s always a trick. In a major foreign loan application, there’ll be a trick to get the money as soon as possible and secure a 10% commission. In a minor activity, like recording a record, there’ll be a trick (voice of a black man, a man singing with a woman’s voice, a strange instrument or a band with an exotic name) to popularize certain music.

That’s why we suggest to the government—which is so distant from our people—that to connect with them, it should add a few articles to laws, decrees, or ordinances, explicitly applying tricks to circumvent them. For example, if a law is passed prohibiting posting signs on walls, the trick would be that signs can be posted by paying five cents per thousand to the city council. Or, if by law it’s forbidden to bring cars from south of the 42nd parallel (free zone), the trick is that upon arrival in Buenos Aires, you can change the license plate for a Federal Capital one at the nearest garage. Or if a Civil Code article prohibits duels in Argentina, the trick is for the government to provide gentlemen going to duel with a modern Aerolíneas airplane to transport them to Colonia, where the duel will be held, if there’s “plafond.”

With these explanations about dodging the law, the government will draw closer to the people and may confidently await the results of the upcoming March elections. Unless Frondizi has some trick up his sleeve like he did two years ago, winning his party a landslide victory.”

DESERVED TRIBUTE

“Puchunguita is charming / my puchunga is a delight / my negra’s hips / measure 122.” Part of Mike Laure’s cumbia, performed with flair by Juan Carlos Colombres, Landrú, was the surprise at the presentation of El que no se ríe es un maleducado!—a compilation of his entire works.

The audience at yesterday’s Golden Hall in the city legislature smiled and applauded Landrú’s wit; he preferred to appear in a homemade video for the tribute offered by colleagues, supporters, and city representatives.

‘I’m not up for violent emotions,’ Landrú apologized to Horacio del Prado, the compiler of the book, who recounted the anecdote and left Landrú’s greeting to his audience in suspense.

It was entertaining to hear him sing and laugh: ‘They invited puchunga / To Ramón’s wake / The dead man saw her hips / Suddenly he was revived by a cumbia,’ attempting to add levity to the recognition of his whole career.

El que no se ríe es un maleducado! is a vast collection of 10 chapters and 462 pages, published by Alpha Text, in which Horacio del Prado (son of Calé, another legendary cartoonist) worked for three years, including forewords by colleagues, historians, Spanish language specialists, and even actress Norma Aleandro, with whom Landrú once shared a radio show.

Distinguished citizen of the city since 2003...(…)

Before and after Tía Vicenta, his genius illuminated the pages of Vea y Lea, Avivato, Pobre Diablo, Rico Tipo, Patoruzú, Sucedió con la Farra, Dinamita, Gente de Cine, Loco Lindo, Leoplan, Gente y la Actualidad, Somos, Mercado, and the newspapers El Mundo and Clarín. In 1971, Columbia University granted him the prestigious Maria Moors Cabot award, the oldest international recognition in journalism.

Among his most remarkable characters are Tía Vicenta, Rogelio ‘the man who reasoned too much,’ Doctor Chantapufi, and Mr. Porcel.

Landrú has satirized Argentine politics from the first term of Juan Domingo Perón in 1945 to the administration of former President Néstor Kirchner. ‘Landrú’s political humor is a silent rasp: it puts the ridiculous in its place,’ summed up the president of the National Academy of Education, Pedro Luis Barcia, who in his usual humorous tone recalled several of Landrú’s absurd jokes.

‘Juan Carlos’s body of work is monumental. His humor does not age; it’s like a great merry-go-round,’ said his colleague Hermenegildo Sábat, current president of the National Academy of Journalism, reviewing his beginnings in graphic journalism alongside Landrú.

Radio journalist Rolando Hanglin called himself a ‘great Landrú fan for life’ and shared personal memories and anecdotes. ‘It was absurdity taken to the extreme,’ Hanglin said about the creator of foundational publications such as Tía Vicenta magazine.

‘We worked together. He is the greatest genius of our small group of humorist journalists. He never insulted. He never attacked. He is a keen observer of trends and social types. He always captured every human type of Buenos Aires with precision and strength, as well as their concepts and ideas,’ he added. In the front row, much of Landrú’s family followed each comment attentively. One of his children, Raúl, attended with many of his children and grandchildren.

Just a little farther back, many friends and colleagues in the humorist’s life gathered, such as Miguel Brascó, Juan Carlos Saravia, José Claudio Escribano, Antonio Requeni, Norberto Firpo, Eduardo Meléndez, Luis Grosman, and Daniel Balmaceda.

Nearly all had comments to share quietly and with nostalgic smiles about comic strip characters adorning the small stage: Señor Porcel, Señor Cateura, Rogelio, María Belén, Tía Vicenta, Jacinto W el Reblan, Sir Jonás el Executive, Gato Clase A, Mirna Delma.

Buenos Aires legislator for the Pro party and vice president of Boca Juniors, Oscar Moscariello, hosted the ceremony in the Golden Hall and recalled the impact that the closure of Tía Vicenta magazine by the military government in 1966 had on his family.

‘As a political humorist, today Landrú would add a touch of humor. He did humorous sociology,’ Moscariello said, describing ‘political humor as an editorial of enormous depth.’

TO PONDER

Why do we laugh when we laugh? The reasons can be many and varied: for instance, when we hear a childish statement that is very mature for the age, observe a wildly nonsensical situation, watch a movie starring Cantinflas, encounter a deceptive, self-serving, triumphant news item, etc.

Also, when we read an old text that could have been written yesterday by its full relevance.

The realization that little or nothing has changed, nor is likely to in the future, is a useful humorous trigger that helps buffer, for example, feelings of disappointment.

When we hear as revealed truth that all past was better, we quickly connect it with false electoral promises touting future wonders.

Gross lies laid bare often bring, at least, a smile alongside indignation.

When the individual and social habit of living with small daily lies is clear—and a rise in that direction is predicted—some humorous process might occur, as when, behind closed doors, we make faces in front of a mirror and candidly recognize ourselves.

LET'S SEE

"Our Editorial. Little Tricks

We know the Argentine people. It's not that the Argentine is a bad people, nor that they don't want to work, nor that they wish to earn the most money with the least effort. The fact is, the Argentine people like little tricks. Tricks for work, for business, for politics, for fun—tricks for everything.

Everyone looks for tricks. In a particular business, the trick is to pluck someone and keep all the money. In the office, the trick is to work as little as possible and charge the maximum overtime. In politics, the trick is the electoral ‘hack’ to get rival votes and win elections. For fun, the trick is to dance and go wild with a “mulata” without anyone noticing. On television, the trick is to get several slots in prime time without being an advertiser, then sell those slots to some commercial firm, and find another trick to slip in ads for other products in the same slot you’ve sold. At customs, the trick is to enter the country without extra charges with 510 cars, 854 typewriters, or 678 television sets. And so on.

That’s why Argentines are so reluctant and adversarial about following the law. If a traffic law is passed, some trick will be found to break it. If a tax law is passed, some trick will be found to evade it. And if a gaming law is passed, some trick will be found to get around it.

We don't know if the authorities know about this Argentine game of tricks. Whether in the biggest and most complicated business, or the most insignificant activity, there's always a trick. In an important foreign loan request, there’ll be a trick to get the money as soon as possible and pocket ten percent commission. And in smaller activities, like recording a disc, there’ll be a trick—a black man's voice, a man singing in a woman's voice, a strange instrument, or a music group with an exotic name—to make some music popular.

Therefore, we suggest to the government, which is so distanced from our people, that to get closer it should add a few extra articles to laws, decrees, or ordinances specifically applying tricks to break them. For example: If a law is published prohibiting people from posting signs on walls, the trick is people can stick signs up if they're willing to pay five cents per thousand to the city council. Or, if by law, bringing cars from the free zone south of parallel 42 is forbidden, the trick is to swap the plates for Federal Capital ones at the nearest garage as soon as you reach Buenos Aires. Or, if the Civil Code forbids dueling in Argentina, the trick will be for the government to make a modern Aerolíneas airplane available to gentlemen who want to duel, to take them to Colonia city, where the duel can take place—if possible.

With these explanations of how to bypass the law, the government will get closer to the people and can confidently await the results of the next March elections. Unless Frondizi has another trick like two years ago and wins a crushing victory for his party.”

DESERVED TRIBUTE

“Puchunguita is a charmer / my puchunga is a wonder / my black woman’s hips / measure 122.” Part of the cumbia by Mike Laure, performed stylishly by Juan Carlos Colombres, Landrú, was the surprise at the presentation of “El que no se ríe es un maleducado!”, the compilation of his entire work.

The audience who came to the Golden Hall of the city legislature yesterday smiled and applauded Landrú’s wit, who preferred to appear in a homemade video for the tribute offered by colleagues, fans, and the city legislators.

‘I’m not up for violent emotions,’ Landrú had apologized to Horacio del Prado, the book's compiler, who shared the anecdote and left the master’s greeting to his audience in suspense.

It was funny to hear him sing and laugh: ‘Puchunga was invited / to Ramón’s wake / the deceased saw her hips / and suddenly came back to life to a cumbia’, trying to deflate the solemnity of the whole tribute.

“El que no se ríe es un maleducado!” is a comprehensive anthology of ten chapters and 462 pages, published by Alpha Text, on which Horacio del Prado, son of Calé (another legendary cartoonist), worked for three years, and which includes prologues from colleagues, historians, Spanish language specialists, and even actress Norma Aleandro, with whom Landrú once shared a radio show.

Distinguished citizen of the city since 2003...

Before and after Tía Vicenta, his genius was found in the pages of Vea y Lea, Avivato, Pobre Diablo, Rico Tipo, Patoruzú, Sucedió con la Farra, Dinamita, Gente de Cine, Loco Lindo, Leoplan, Gente y la Actualidad, Somos, Mercado, and the newspapers El Mundo and Clarín. In 1971, Columbia University granted him the prestigious María Moors Cabot Prize, the oldest international award in journalism.

His most outstanding characters include Tía Vicenta, Rogelio “the man who thought too much”, Doctor Chantapufi and Señor Porcel.

Landrú has satirized Argentine politics since the first term of Juan Domingo Perón in 1945 up to the government of former President Néstor Kirchner. “Landrú's political humor is an unsparing file: it brings the ridiculous down to size,” summarized the president of the National Academy of Education, Pedro Luis Barcia, who, in his usual humorous style, recalled some of Landrú’s most absurd jokes.

“The sum of Juan Carlos’s work is monumental. His humor doesn’t age—it’s a great merry-go-round,” said his colleague Hermenegildo Sábat, current president of the National Academy of Journalism, remembering his early days in graphic journalism alongside Landrú.

Radio journalist Rolando Hanglin called himself “a lifelong Landrú fanatic” and shared memories and personal anecdotes. “It was absurdity taken to the extreme,” Hanglin said of the creator of foundational publications such as the magazine Tía Vicenta.

“We have worked together. He is the greatest genius in our small guild of comic journalists. He never offended. He never attacked. He is a great observer of social trends and types. He always precisely and vigorously captured all the human types in Buenos Aires, and also their concepts and ideas,” he added. In the front row, much of Landrú’s family listened closely to every comment. One of his children, Raúl, attended with several of his children and grandchildren.

A little further back, many friends and colleagues from the humorist’s life shared the scene, like Miguel Brascó, Juan Carlos Saravia, José Claudio Escribano, Antonio Requeni, Norberto Firpo, Eduardo Meléndez, Luis Grosman and Daniel Balmaceda.

Almost all had comments to make quietly, with a nostalgic smile, about the cartoon characters adorning the small stage: Señor Porcel, Señor Cateura, Rogelio, María Belén, Tía Vicenta, Jacinto W el Reblan, Sir Jonás el Executive, Gato Clase A, Mirna Delma.