Cuando se habla de la tradición literaria de la tierra de Trump, se piensa en el nobel y autores consagrados (Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Steinbeck, Dos Passos, etc.), pero raramente se toma en cuenta a gente como Edward Abbey (1927-1989), quien escribe sobre la parte que en verdad es 100% norteamericana: el paisaje del sureste. Muchos autores famosos norteamericanos lo son porque a los propios estadounidenses les suenan europeos, como si la nostalgia por el llamado viejo continente les fuera irresistible. En todo caso, habría que establecer la importancia de los autores locales que hablan de temas locales y, sobre todo, con léxico local. Como sucede con el humor, en la literatura lo más local es más universal: la necedad de ser asequible por un público de distintos países y lenguas termina por hacer un producto neutro que a pocos interesa. Incluso en el doblaje de películas, al menos en español, se distingue entre el de España y el de Latinoamérica. abbey hace de la problemática norteamericana un discurso universal: la depredación ambiental con el consentimiento del estado y la indiferencia de la población. Pero sus personajes sólo pueden ser norteamericanos, por la génesis de cada uno de ellos.

Toda acción social termina por ser política. Y si alguien hace del panorama de montañas y desierto un escenario político, es Abbey, cuyo humor literario es destacable al mezclar la locura ambientalista y anárquica de sus personajes con el ángulo norteamericano donde el individuo siente que realmente es el centro de los derechos y que el famoso día en la corte es sinónimo de que una sola persona puede confrontar al país entero. En países como México esto llama al humor en la política, pues hoy, como hace 60 años, son las horas que el señor presidente diga que son. Pero, aquí y en todo el mundo, para encontrar el humor en la política es necesario acudir, por lo menos, a quienes hacen verdadera política, no a los que se vuelven bufones involuntarios en esta temporada donde el populismo se ha vuelto sinónimo de seria ignorancia seria. Claro, tales discursos perniciosos y sus caraduras exponentes no son exclusivos del llamado (por ellos mismos) como el país más grande. Debe ser demasiada grandeza gringa donde ha soportado un populismo que desvirtúa los principios centrales que hicieron grande a ese país: es un chiste mal contado, un mal emulo del marxismo. De Groucho Marx, por supuesto: para mostrar lo grande que somos, dejaremos de serlo. Cuando se hablaba de inclusión, de la tierra de los libres, del libre mercado y, sobre todo, del american way of life -dícese del modo de vivir, donde el esfuerzo es recompensado y las leyes son justas-, ahora es todo al contrario. Como si Gilbert y Sullivan los reyes del “mundo al revés” (en inglés topsy-turvy) cantaran una opereta para hablar de que la fuerza se gana desde el miedo del emitente. Se cierran fronteras porque se teme perder ante el rival más fuerte comercialmente, más hábil en la hechura de bienes que se consumen en los EUA, como los coches, por decir lo menos. Ahí está el humor, pero el que llama al absurdo: se ríe quien entiende que, en la ilógica política del político criminal (se le ha encontrado culpable de varios delitos, pero allá como acá, dicen, las urnas purifican o anulan), que preside a los EUA, pregonada como benéfica para la población que aplaude, se esconde la inexorable tragedia de quien cierra los ojos. No hay burla de las personas, sí del concepto donde la realidad antagónica al discurso emergerá para sorprender a quienes esperan lo contrario. Si uno de los mecanismos de la risa es la sorpresa, la política y sus mentiras llevarán al golpe inesperado, cual pastelazo del cine mudo, cuando los votantes de nuca roja perciban que el dinero no les alcanza para comprar las vituallas mensuales, que los servicios de salud están decayendo o que la inseguridad los ha alcanzado en sus domicilios o en la escuela de sus hijos a pesar de que pueden comprar armas de todo tipo en el super de la esquina. La mecanización que proclama Bergson como componente de la risa, está en la tragedia cuando se mira con ojos críticos. Mirar cualquier dolor humano es parte del humor: chico o grande, individual o colectivo, en la era de la corrección política que lleva al extremo del eufemismo, las criaturas asesinadas por jóvenes o adultos enajenados forman parte del análisis de una sociedad donde hay quien está dispuesto a morir por preservar el rancho y sus montañas, como Abbey, mientras que en otros lugares del inmenso país, las personas mueren por asfixia en los camiones que son abandonados por los traficantes de indocumentados. Habrá a quien se le salga un hipo de risa cuando se compare la importancia de una vida humana con un ecosistema entero. Humanos sobramos, dirán con un dejo de cinismo sonriente los que miran desde afuera, pero si yo he de morir, no me importa que se pierdan las montañas más hermosas en los atardeceres meridionales del invierno, dirá con más cinismo quien mire desde adentro tal conflicto. En el humor, la contraposición de lo extremo siempre funciona: tratar de asimilar lo que nunca será afín sólo puede llevar a la contraposición absurda. Abbey es un paladín de la lucha que hoy parecemos perder los mirones del humor: la de la corrección política. No importa matar o depredar, hay que hacerlo sin herir susceptibilidades o sin confrontar al interlocutor. Al fin que, para encontrar culpables, pocos le ganan a los populistas de todas las latitudes.

El imaginario colectivo identifica a esa nación con los indios y sus contrarios: los vaqueros y los colonos (más los militares) que tanto mataban gente como bisontes o dragaban ríos para obtener oro: el viejo oeste, rezan los gringos. En una era donde los “políticamente correcto” se vuelve eufemismo para ocultar el saqueo ambiental a la propia nación, las letras del rebelde Abbey y sus entrañables personajes permanecerán como parte de esa literatura que habla de la nación profunda, la que nos han querido ocultar. Su novela mayor es “La banda de la tenaza” (“The monkey wrench gang”, 1975), donde refleja parte de su propia biografía como ambientalista feroz y trabajador eventual itinerante, pero suelta el humor a la menor provocación. Hay que tenerlo para luchar de frente con toda la fuerza del estado. Quien mira con la tragedia como lente diluyente, termina por ampliar su mala percepción; quien usa el humor para lidiar con la realidad, es capaz de encontrarle lo divertido hasta a lo más aberrante.

“La banda” narra las peripecias de cuatro personajes que encarnan partes destacadas de la sociedad norteamericana: está George Washington Hayduke, el excombatiente de Vietnam, quien ha sido afectado por la guerra y es una máquina de pelear (en una persecución policiaca, baja un jeep en rapel libre, volándolo por una acantilado); Bonnie Abbzug, la joven guapetona e instruida que practica el amor libre, en alusión a la llamada “revolución sexual”; “Seldom Seen” Smith, el guía en las montañas del desierto que tiene 3 esposas, de acuerdo a su religión protestante; y Doc Sarvis, el doctor que patrocina las expediciones en que obstruyen la construcción de obras de infraestructura en el desierto y destrozan las ya existentes. Cada uno contiene una veta clara de la identidad norteamericana, ya sea como ciudadano utilizado por el estado mercantilista (¿cuántos chistes se habrán hecho sobre la locura de ir a un país no limítrofe para matar a personas que jamás podrían haber viajado siquiera fuera de su comarca y decir que son un peligro para el pueblo norteamericano?), o como el pueblo que revoluciona las viejas ideologías, o como una muestra de la insospechada convivencia de religiones que hay en EUA, o como quien comprende que sin dinero no hay modo de actuar. Al grito de “conservemos la naturaleza”, lo mismo tiran publicidad, que rompen puentes o descarrilan ferrocarriles. Después de varias fechorías, las policías y sus ayudantes ponen todos sus esfuerzos en capturarlos. Destaca entre estos un reverendo: espera ser gobernador con tal detención. Otro guiño humorístico: pregona la espiritualidad, pero busca conseguir la represión dizque legal para llegar al poder. Debe ser muy buena esa vida espiritual, dirán los estandoperos. La lectura de los enfrentamientos entre los “buenos” y los “malos” contrapone el viejo concepto (¿o habría que decir “del original concepto”?) del humor: el humor como entidad vital, un cuerpo cuyos efluvios (que hoy dirán hormonales) corresponden a los de una persona de acción y alegría, por un lado; por el otro lado se encuentran los representantes del estado que tienden más al thanatos que va inserto en el orden inflexible. Lo natural de nombre es adecuarse a las contingencias cotidianas, es el humor natural; la contrapartida es la necedad humana de encuadrar al mundo a sus deseos, mediante leyes absurdas que son una promesa de muerte por acabar con condiciones ambientales propicias para el desarrollo básico humano. El humano es el ser pasajero, no el mundo a su alrededor.

Con una prosa por momentos demasiado detallista, es fácil advertir la perspectiva del autor sobre cómo el verdadero oeste norteamericano lo constituye el paisaje. Casi al final de la persecución, Hayduke narra a sus compinches cómo sobrevivió a los vietnamitas durante la guerra en que fue hecho prisionero: pensando en las montañas, los ríos y el paisaje del desierto: lo que verdaderamente diferencia esa región del resto del planeta. Los personajes se concentran en el horizonte y cómo se pierde con la mano del hombre, cómo las presas significan la muerte para animales y su entorno. El autor ni siquiera se preocupa por analizar a los indios, casi los desprecia por su participación cómplice en ese deterioro ambiental; como si los pocos indios que sobrevivieron al siglo XIX tuvieran la capacidad para enfrentar al apabullante aparato militar de la posguerra mundial. Debe ser un mal chiste. Smith incluso le reza en voz alta a su Dios para que acabe con las obras humanas que minan el paisaje, donde es más evidente la rectoría de las compañías industriales. Doc le explica a Bonnie que la nación entera está siendo depredada por esos intereses económicos desentendidos de las consecuencias de sus abusos al ecosistema.

Esta crítica tan directa, sin embargo, está plagada de ocurrencias y divertimentos. Los personajes llegan a vivir momentos tan inverosímiles que dan risa. Lo que en parte se logra con las ilustraciones del genio del underground, Robert Crumb, que acompañaron a la edición conmemorativa de los primeros diez años de la aparición de esta novela. Un acierto, pues Abbey y Crumb se han mantenido como íconos de esa parte de la creación norteamericana, la que insiste en que el “desarrollo económico” no deja de tener sus consecuencias sangrantes y que el beneficio no es para todos en un país lleno de contrastes. Claro que el análisis de Crumb da para muchísimo más, pero aquí lo dejamos como refuerzo de las peripecias literarias del buen Abbey. Las diversas crisis económicas de los Estados Unidos evidencian que en el país más rico de la Tierra no hay equidad en la distribución de servicios, de libertades ni de posibilidades de crecer. Peor si eres inmigrante. Otro chiste que se cuenta solo: el presidente que más ha luchado en el discurso contra los inmigrantes es hijo y nieto de inmigrantes; encima, dos de sus esposas son inmigrantes: ya pronto se ve que hay trabajos que ninguna mujer norteamericana quisiera hacer y se lo deja a las inmigrantes: casarse con Trump e intentar soportarlo. La visión contrapunteada de los ayudantes de policía contra la de los libertarios es sólo una muestra de ese humor que se contrapone al orden devastador. En algún momento Hayduke y Bonnie llegan a un bar donde los rancheros incultos se entretienen bebiendo cerveza y el excombatiente se divierte retándolos con su supuesta condición de jipi, luego de “marica” y al final, cuando se revela como Boina Verde, el silencio le contesta: incluso quienes sólo saben del trabajo cotidiano, reconocen la violencia como rectora de la vida nacional norteamericana, pero el divertimento por el engaño está ahí.

Quizá por el año de publicación, pero destaca la falta de señalamientos a los indocumentados que ahora cruzan por miles los estados de Arizona, Nuevo México y Utah, donde transcurre la novela. Se puede aventurar que para Abbey no importan, por no dañar el desierto; o, quizás, simplemente están fuera de la ecuación empresas-deterioro.

Identificable como parte de la literatura anarquista no india, podría señalarse a Abbey como una ramificación de la generación beat en tanto desconfía del Estado y propone su desaparición: Hayduke sueña en vivir en la soledad del desierto, alimentándose de animales y vegetales (en algún momento, incluso come un poco de arena roja). Aquí la insurrección es directa: cualquier máquina es digna de ser destruida, cualquier vía que corte el paisaje estorba, cualquier afectación a la naturaleza es reprochable. Mientras Hayduke carga armas y las usa en defensa, los demás insisten en luchar con la inteligencia, hasta que se topan con los violentos ayudantes de sheriff que piensan en hacer respetar la ley como pretexto para someter a quien no les gusta. Cuando la persecución está a punto de volverse mortal para los anarquistas, uno de los perseguidores tiene un infarto y piden ayuda al Doctor, en una metáfora de cómo aún los más conservadores tarde o temprano habrán de necesitar a aquellos que repudian. Abbey recuerda el sentido de lo social por encima del Estado. Si bien los personajes actúan con una ideología no ordenada que no oculta su intención en hacernos sonreír (“Iremos creando nuestra doctrina con la práctica, eso nos garantizará coherencia teórica”) hay una rebeldía empírica que no es aislada. En uno de sus sabotajes se encuentran con un solitario de rostro tapado que les avala en su destrucción: también la practica.

Una novela indispensable para comprender cómo las visiones autocríticas sobreviven al paso del tiempo, con un dejo de humor: “cuando oigo la palabra ´cultura´, saco la chequera”. En el país de la gran promesa todo es cuantificable. Mientras en otros países es indispensable preservar los valores culturales por entender que no hay manera de ponerle precio a un objeto cultural, Abbey se burla en voz de sus personajes de esa manía gringa de comprar y vender todo.

Donde otros prefieren sufrir, yo prefiero reír.

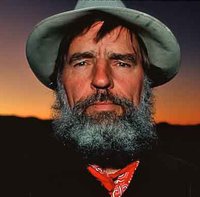

Edward Abbey

Abbey, the Rebel

by Ricardo Guzmán Wolffer

When people talk about the literary tradition of the land of Trump, they think of Nobel laureates and classic authors (Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Steinbeck, Dos Passos, etc.), but rarely do they take into account writers like Edward Abbey (1927-1989), who wrote about what is truly 100% American: the landscape of the Southwest. Many famous American authors are so regarded because to Americans themselves, they sound European, as if nostalgia for the so-called Old Continent were irresistible. In any case, it is worth emphasizing the importance of local authors who write about local themes and, above all, use local language. As happens with humor, in literature, the more local something is, the more universal it becomes: the necessity to reach audiences from other countries and languages ends up generating a neutral product that interests few. Even in movie dubbing—in Spanish, at least—there is a distinction between dubbing from Spain and from Latin America. Abbey turns American issues into a universal narrative: environmental destruction with the consent of the government and the indifference of the population. But his characters can only be American, by the nature of their origins.

Every social action ends up being political. And if anybody transforms the landscape of mountains and desert into a political stage, it’s Abbey, whose literary humor stands out by blending the environmentalist and anarchic madness of his characters with the American perspective, where the individual truly feels at the center of rights and the famous “day in court” is synonymous with one person confronting an entire country. In countries like Mexico, this calls for political humor, because today, as sixty years ago, time is whatever the president says it is. But, here and around the world, to find humor in politics you have to go—at the very least—to the ones who do real politics, not to those who become accidental jesters in this season where populism has become synonymous with serious ignorance. Of course, such harmful discourses and their brazen proponents are not exclusive to the so-called (by themselves) greatest country. It must take enormous American greatness to have survived a populism that distorts the central principles that made the country great: it’s a badly told joke, a poor imitation of Marxism. Groucho Marx, of course—showing how great we are by ceasing to be so. When people spoke of inclusion, the land of the free, the free market and above all, the American way of life—meaning a way of living where effort is rewarded and laws are just—now, it is all the opposite. As if Gilbert and Sullivan, kings of “topsy-turvy,” were singing an operetta about power being gained by the issuer’s fear. Borders close because people fear losing to a stronger commercial rival, more skilled at making goods consumed in the USA, like cars, just to name one. That’s the humor—but it’s the humor of the absurd: you laugh if you understand that, in the illogical politics of the criminal politician (he’s been found guilty of several crimes, but there as here, they say the ballot box purifies or cancels out), who presides over the USA, declared as beneficial for the population that applauds, lies the inexorable tragedy of those closing their eyes. There’s no mockery of individuals, but rather of the concept, in which the reality in opposition to the rhetoric will emerge to surprise those expecting the opposite. If surprise is one of the mechanisms of laughter, politics and its lies will deliver the unexpected blow—like a silent-film pie-in-the-face—when the redneck voters realize their money isn’t enough for monthly groceries, healthcare is declining, or insecurity has reached their homes and their children’s schools, even though they can buy any kind of gun at the nearest supermarket. The mechanization Bergson described as a component of laughter is present in tragedy when viewed critically. Observing human suffering is part of humor—big or small, individual or collective. In an age of political correctness taken to the extreme of euphemism, creatures murdered by deranged youth or adults are part of the analysis of a society where some are willing to die for their ranch and mountains, like Abbey, while elsewhere in this vast country, people die by suffocation in trucks abandoned by human traffickers. Some may let out a hiccup of laughter when comparing the importance of a human life to that of an entire ecosystem. “There are too many humans,” say those who look on with a smirk of cynicism from outside, but “if I must die, I don’t care if the most beautiful mountains in the southern winter sunsets are lost,” might say with even greater cynicism someone inside that conflict. In humor, the juxtaposition of extremes always works: trying to assimilate what can never truly fit only leads to absurd contrasts. Abbey is a champion of a struggle that, as onlookers on humor, we seem to be losing today: the fight with political correctness. It doesn’t matter whether you kill or consume—you just have to do it without hurting sensibilities or confronting your interlocutor. After all, when it comes to finding scapegoats, few can beat populists from any latitude.

The collective imagination associates that nation with Indians and their opposites: cowboys and settlers (plus the military), who killed people as well as bison, or dredged rivers for gold—the old west, as Americans say. In an era where “political correctness” is used as a euphemism to cover up environmental pillaging of their own nation, Abbey the rebel’s writing and beloved characters remain part of a literature that speaks of deep America, the one kept hidden from us. His greatest novel is “The Monkey Wrench Gang” (1975), which reflects part of his own biography as a ferocious environmentalist and occasional itinerant worker, but he releases humor at any provocation. It’s essential for the fight against the full powers of the state. Seeing life only through the lens of tragedy leads to a flawed perspective; using humor to deal with reality helps you see what’s amusing even in the most appalling things.

“The Gang” narrates the adventures of four characters that embody key facets of American society: George Washington Hayduke—the Vietnam veteran affected by war, a fighting machine (in a police chase, he rappels from a jeep, sending it off a cliff); Bonnie Abbzug—the educated and attractive young woman who practices free love, referencing the “sexual revolution”; “Seldom Seen” Smith—the desert mountain guide with three wives according to his Protestant faith; and Doc Sarvis—the doctor who sponsors the expeditions that block new infrastructure projects in the desert and destroy the ones already built. Each one reflects a clear vein of American identity, whether as a citizen used by the mercantile state (how many jokes have been made about the madness of going to a non-bordering country to kill people who could never have traveled outside their county and saying they’re a threat to Americans?), as the people who revolutionize old ideologies, as unexpected evidence of the coexistence of religions in the USA, or as those who realize there is no way to act without money. Shouting “Let’s save nature!”, they tear down ads, break bridges, or derail trains. After several misdeeds, the police and their helpers spare no effort to capture them. Among them stands out a reverend: he hopes to become governor with such restraint. Another humorous wink: he preaches spirituality, yet seeks to enforce repression—supposedly legal—in order to gain power. That spiritual life must be a good one, stand-up comedians might say. The reading of the confrontations between the “good” and the “bad” contrasts with the old concept (or should we say “the original concept”?) of humor: humor as a vital entity, a body whose effluvia (nowadays we would say hormonal) belong to a person of action and joy, on one side; on the other, the representatives of the State, who tend more toward the thanatos inherent in rigid order. The natural human tendency is to adapt to everyday contingencies—that’s natural humor; its counterpart is the human stubbornness of forcing the world into one’s desires through absurd laws that promise death by destroying the environmental conditions necessary for basic human development. Humans are the transient beings, not the world around them.

With prose at times overly detailed, it’s easy to perceive the author’s perspective that the true American West is defined by its landscape. Near the end of the chase, Hayduke tells his companions how he survived the Vietnamese during the war, when he was captured: by thinking of the mountains, the rivers, and the desert landscape—the elements that truly distinguish that region from the rest of the planet. The characters focus on the horizon and how it disappears under the hand of man, how dams mean death for animals and their environment. The author doesn’t even bother to analyze the Native Americans—he almost despises them for their supposed complicity in this environmental deterioration, as if the few who survived the nineteenth century had the means to confront the overwhelming postwar military apparatus. That must be a bad joke. Smith even prays aloud to his God to destroy the human works that undermine the landscape, where the rule of industrial corporations is most evident. Doc explains to Bonnie that the entire nation is being ravaged by those economic interests that ignore the consequences of their abuses against the ecosystem.

This direct criticism, however, is full of witty remarks and amusements. The characters experience moments so implausible they become funny. This effect is partly achieved through the illustrations of underground genius Robert Crumb, which accompanied the tenth-anniversary commemorative edition of the novel. A wise choice, since Abbey and Crumb have remained icons of that part of American creativity that insists “economic development” always has its bleeding consequences, and that the benefits are not shared equally in a country of stark contrasts. Of course, Crumb’s work deserves a much broader analysis, but here we leave it simply as a reinforcement of Abbey’s literary escapades. The various economic crises in the United States show that, in the richest country on Earth, there is no equity in the distribution of services, freedoms, or opportunities for growth. Worse still if you are an immigrant. Another self-telling joke: the president who has most fiercely spoken against immigrants is himself the son and grandson of immigrants—and, on top of that, two of his wives are immigrants. It quickly becomes clear there are jobs no American woman would want to do, leaving them to immigrants: marrying Trump and trying to put up with him. The contrasting visions of the deputy sheriffs and the libertarians are just one example of the kind of humor that opposes a devastating order. At one point, Hayduke and Bonnie enter a bar where ignorant ranchers entertain themselves drinking beer, and the ex-soldier amuses himself by provoking them—first posing as a hippie, then as a “sissy,” and finally revealing himself as a Green Beret. Silence answers him: even those who only know hard labor recognize violence as the guiding principle of American national life—but the fun in deception remains.

Perhaps due to the year of publication, what stands out is the absence of references to the undocumented migrants who now cross by the thousands through Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, where the novel takes place. One could guess that Abbey doesn’t mention them because they do no harm to the desert—or perhaps they simply fall outside the companies-deterioration equation.

Identifiable as part of non-Indian anarchist literature, Abbey could be seen as a branch of the Beat Generation, as he distrusts the State and proposes its disappearance. Hayduke dreams of living in the solitude of the desert, feeding on animals and plants (at one point he even eats a bit of red sand). Here, the insurrection is direct: any machine is worthy of destruction; any road cutting through the landscape is an obstacle; any harm to nature is reprehensible. While Hayduke carries and uses weapons in self-defense, the others insist on fighting with intelligence—until they meet the violent deputy sheriffs who claim to uphold the law as an excuse to subdue those they dislike. When the persecution is about to turn deadly for the anarchists, one of their pursuers suffers a heart attack, and they call for the Doctor’s help—a metaphor for how even the most conservative will eventually need those they despise. Abbey recalls the social sense above the State. Although the characters act with a disorganized ideology that doesn’t hide its intention to make us smile (“We’ll build our doctrine through practice—that will guarantee our theoretical coherence”), there’s an empirical rebellion that is far from isolated. In one of their acts of sabotage, they meet a masked loner who endorses their destruction—and practices it himself.

An indispensable novel for understanding how self-critical visions endure over time—with a hint of humor: “When I hear the word ‘culture,’ I reach for my checkbook.” In the land of the great promise, everything has a price tag. While in other countries it’s essential to preserve cultural values because there’s no way to assign a price to a cultural object, Abbey mocks—through his characters—that American obsession with buying and selling everything.

Where others prefer to suffer, I prefer to laugh.

(This text has been translated into English by ChatGPT)