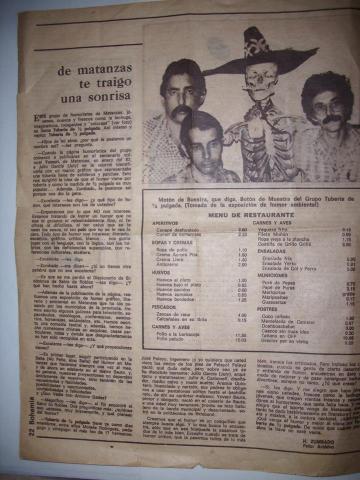

La Seña del humor fue un grupo atípico de humor escénico, creado en la ciudad de Matanzas Cuba en 1984. De inmediato se dio a conocer en toda la Isla y se convirtió en un fenómeno popular, a pesar de tener siempre la crítica a favor. Se debió al tipo de humor que hacían: fresco, irreverente, absurdo, elaborado, con buen gusto, con referencias culturales, pero al alcance de todos. Para muchos fue un aporte al humor teatral cubano, porque de una manera inteligente y acorde a los tiempos, le daba continuidad al teatro vernáculo cubano. A partir de su fundación y consolidación, innumerables grupos comenzaron a surgir en Cuba siguiendo su camino, en lo que se ha llamado "Movimiento del Nuevo Humor Cuba". (Nota de Humor Sapiens).

EL HUMOR DE LOS DIRECTORES DE LA SEÑA DEL HUMOR DE MATANZAS, CUBA.

Hay muchos tipos de humor, una de las tantas diferencias es si se hace humor desde el poder o a pesar del poder. Aramís y Pelayo, su grupo: La Seña del Humor, no eran quienes dictaban las reglas.

Cuando uno no es quien dicta las reglas, puede elegir hacer un humor que busca ganarse favores o congraciarse con el poder de turno, un humor que se arrima y busca sentirse protegido, aún a costa de lo que para uno puede ser humillante. Sin embargo, ellos, el único favor que buscaban era el del público, y tampoco a costa de complacerlo con lo que fuera.

Hacer humor si uno no es el que dicta las reglas, y si tampoco quiere hacer lo que sea con tal de que la gente se ría, tiene sus riesgos. La sala se puede quedar vacía poco a poco, pueden cerrarte espacios de difusión y de trabajo. No era lo que ocurría con ellos. Las salas se llenaban, la gente se reía a mandíbula batiente, eran muy solicitados. Tal era así que podríamos afirmar que avanzaban contra las reglas, a pesar de ellas. Eran una programación, buenamente obligada. Su fama no se debía a que apoyaban ninguna causa especial, ni a un fenómeno de promoción. ¿Por qué lo hacían y qué encontraba el público en ellos?

Creo que algo más que un momento de diversión. No se trataba de ir al teatro a olvidar los problemas, sino de hacerlo para recordar que somos personas. Y con esto no quiero ponerlos como héroes, porque por suerte no lo eran ni necesitaban serlo. Describo el núcleo de su encuentro con el público y, así como ellos, el de tantos buenos actores y grupos. El secreto es el mismo: hay quienes hacen chistes para olvidar los problemas, y cuando los hacen nos dicen: “Riámonos un rato, porque los problemas seguirán ahí”; y hay quienes hacen chistes para denunciar los problemas, para que los inconvenientes no nos transformen en alguien que no somos. Que un día nos miremos al espejo y digamos: “Yo no era éste”, o bien: un día nos encontremos con un viejo paisaje familiar y nos preguntemos en quién nos hemos convertido, deslizándonos, sin advertirlo.

En la sala, durante los juegos y la risa, hay un tipo de humor, no todos, un tipo de humor que hace que nos riamos y nos recordemos al mismo tiempo. Ese pequeño momento de placer y de triunfo en el que somos grandes, somos niños y seres sin edad, es la apuesta que vale la pena, el riesgo, y la de satisfacción más plena.

Esos fueron el Pelayo y el Aramís, la Seña del Humor, que conocí. Un estilo que tenía inteligencia mezclado con candor e ingenuidad; algo de absurdo, abstracto con algo de fibra popular, y trabajo: ensayos, guiones, buena música; que implicaba riesgos y no era complaciente con eso que erróneamente se llama: “lo que el público quiere”.

Vladimir Propp, en su análisis estructural del cuento popular, habla de uno de los momentos, que pueden aparecer en un relato: “desenmascarar al falso héroe”. Esa es, precisamente, una de las funciones de cierto humor: desenmascarar (al falso héroe, al falso discurso, y al falso triunfo).

La gente aplaudía eso que tiene que ver con la vitalidad, pero también con la dignidad. Agradecía la risa y ser tratados como personas, como historias individuales, con fracasos que no humillan (salvo que necesitemos esconderlos). Y cuando admitimos todo eso recién entonces es posible la esperanza. Eso es lo que creo que les agradecían.

Este artículo sirvió de prólogo al libro Bienaventurados los que ríen de los autores Aramís Quintero y Pepe Pelayo, publicado por la Editorial Humor Sapiens, 2007 (Nota de Humor Sapiens).

The humor of the directors of La Seña del Humor in Matanzas, Cuba

By Luis Pescetti

La Seña del Humor was an atypical scenic humor group, created in the city of Matanzas, Cuba, in 1984. It quickly became known throughout the Island and turned into a popular phenomenon, despite always having the critics on its side. This was due to the kind of humor they produced: fresh, irreverent, absurd, sophisticated, tasteful, full of cultural references, yet accessible to everyone. For many, it was a valuable contribution to Cuban theatrical humor, because in an intelligent way and in tune with the times, it continued the tradition of Cuban vernacular theater. From its founding and consolidation, countless groups began to emerge in Cuba following its path, in what came to be known as the “New Cuban Humor Movement.” (Note from Humor Sapiens).

THE HUMOR OF THE DIRECTORS OF LA SEÑA DEL HUMOR FROM MATANZAS, CUBA

There are many types of humor, and one of the many distinctions is whether humor is made from power or in spite of power. Aramís and Pelayo, with their group La Seña del Humor, were not the ones dictating the rules.

When you are not the one dictating the rules, you can choose to do humor that seeks favors, that tries to curry sympathy with those in power, a humor that cozies up to authority to feel protected, even at the cost of one’s own dignity. But they, the only favor they sought was that of the audience—and not even at the cost of pleasing it with just anything.

Doing humor when you’re not the one setting the rules, and when you also refuse to do whatever it takes just to make people laugh, carries its risks. The theater may gradually empty, the spaces for dissemination and performance may be closed to you. But that was not the case with them. The theaters filled up, people roared with laughter, they were in high demand. So much so, that one could say they were advancing against the rules, despite them. They were a program that, in a way, had to be included. Their fame did not come from supporting any special cause, nor from promotional hype. Why did they do it, and what did the audience find in them?

I believe it was something more than a moment of entertainment. It was not about going to the theater to forget problems, but rather to remember that we are human beings. And I do not mean to portray them as heroes—fortunately, they were not, nor did they need to be. I am describing the core of their connection with the audience, and, like them, of so many good actors and groups. The secret is the same: some tell jokes to make us forget our problems, and when they do, they are really saying: “Let’s laugh for a while, because the problems will still be there.” And others tell jokes to denounce the problems, so that difficulties do not transform us into someone we are not. So that one day, when we look in the mirror, we don’t say: “This isn’t who I was,” or so that, upon encountering a familiar old landscape, we don’t wonder who we’ve become—having drifted without realizing it.

In the theater, during the playfulness and laughter, there exists a certain type of humor—not all humor, but one kind—that makes us laugh and remember at the same time. That brief moment of joy and triumph, in which we are both great and childlike, ageless beings, is the wager that is worth it: the risk, and the fullest satisfaction.

That was Pelayo and Aramís, the Seña del Humor I knew. A style that mixed intelligence with candor and innocence; absurdity with abstraction and popular flair; and above all, hard work: rehearsals, scripts, good music. It was a humor that carried risks, and was never complacent with what is mistakenly called “what the audience wants.”

Vladimir Propp, in his structural analysis of folktales, describes one possible function that may appear in a story: “unmasking the false hero.” That is precisely one of the roles of certain humor: to unmask—the false hero, the false discourse, the false triumph.

The audience applauded that kind of humor, which is about vitality but also about dignity. They appreciated laughter, but also being treated as human beings, as individuals with their own stories, with failures that do not humiliate (unless we need to hide them). And it is only when we admit all of this that hope becomes possible. That, I believe, is what the audience thanked them for.

This article served as the prologue to the book Blessed Are Those Who Laugh by authors Aramís Quintero and Pepe Pelayo, published by Humor Sapiens Editorial, 2007. (Note from Humor Sapiens).

(This text has been translated into English by ChatGPT)