Rumania es el país más conocido por el terror del Conde Drácula que por su humor, sin embargo en el contexto de los concursos internacionales de humor gráfico tiene una fuerte presencia de participantes y ganadores, por eso invité al ya premiado en Portugal, Constantin Pavel para contarnos sobre el estado de ánimo de su país.«El rumano usa el humor para “reírse de los problemas” y la justificación podría ser el hecho de que a lo largo de la historia siempre hemos tenido muchos problemas. Solo que, después de conocer el humor de otros pueblos, entendí que los rumanos no tienen los derechos de autor sobre este principio. Hay muchos otros lugares en el mundo donde también se ríen de esta manera y tengo que decir que creo que por eso dicen que el lenguaje del humor es universal. Todos se ríen de la misma manera y los mecanismos son los mismos en todas partes».

Pero, ¿realmente no hay nada diferente? “Alrededor del 44% de la población rumana vive en áreas rurales. La media de la Unión Europea es del 25%. Por eso, el humor rumano lleva la impronta de esa ruralidad, un humor popular y campesino, un humor sano y vivo, refinado a lo largo de cientos de años. El origen de nuestro pueblo es dacio-romano. El Imperio Romano logró conquistar muchos territorios, subyugando gran parte de Europa hoy en día, pero las conquistas no se detuvieron aquí, continuando en África e incluso en Asia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Babilonia... llevándose rumanos y trayendo culturas y eso hizo que los rumanos tuvieran mucho humor heredado de los que emigraron y que tienen la impresión de que conquistaron el mundo.

La influencia otomana trajo nuevos personajes y situaciones a la cultura rumana. Un conocido descendiente del mundo fanariota es el personaje Nastratin Hogea, creado por Anton Pann (1790/1854) (inspirado en el sufí Nasreddin Hoca). Este folclorista, poeta, músico fue conocido por sus parábolas llenas de humor y sabiduría, chistes sobre los gitanos, una minoría étnica. Los temas principales son el robo, la negativa a trabajar, muchos niños; en esencia, todos los estereotipos negativos sobre los romaníes en Rumanía. Estos estereotipos de gitanos o gitanos denunciados en el siglo. XIX siguen vigentes. Son uno de los grupos étnicos minoritarios más grandes de Rumania (3% de la población total). Su humor es muy natural, fruto de su estrecha relación con la naturaleza y la realidad. Sencilla y auténtica, desprovista de las mentiras del mundo civilizado, refleja el humor ancestral de la antigüedad.

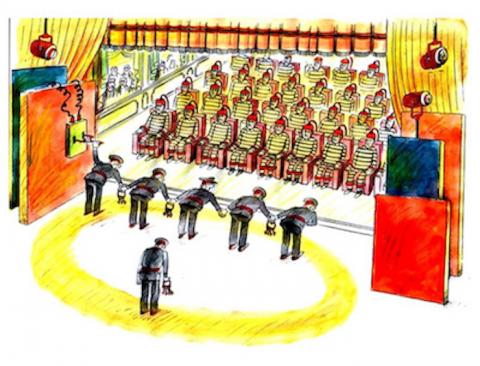

El humor rumano es más evolucionado, desarrollado en otra etapa civilizatoria y con refinados aspectos y condiciones del comunismo. Por ejemplo, antes de la Revolución no era fácil ser comediante. Había censura comunista y había que tener mucho cuidado para que no aparecieran en el espacio público mensajes subversivos y anticomunistas, considerados peligrosos para el régimen. Pero, por otro lado, tenía una ventaja creativa. Los humoristas se vieron obligados a buscar medios de expresión sutiles, ocultos, mucho más inteligentes y sofisticados para evadir la censura y llegar al público. Este ejercicio permanente, durante años, mejoró la calidad del humor rumano».

¿Este humor, en que genero expresión artística se expresa mejor? "En todas. Es difícil elegir solo uno. Por ejemplo, en las letras no puedo dejar de mencionar a George Topîrceau, Ion Creangâ, Vlad Musatescu… o los dramaturgos Ion Luca Caragiale, Constantin Tanase y Tudor Musatescu, que se convirtieron en auténticos iconos del humor y el espíritu rumanos.

Junto a ellos, hay una galería de actores muy importantes: Puiu Călinescu, Jean Constantin, Amza Pellea, Toma Caragiu, Dem Rădulescu, Ștefan Bănică y Stela Popescu.

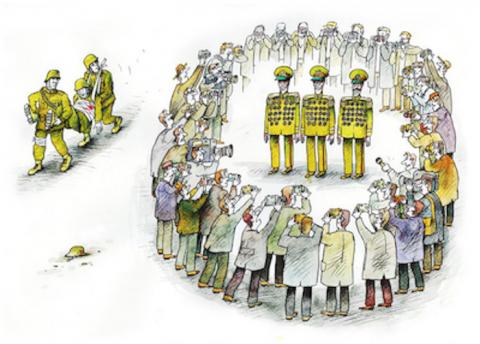

Todo esto también es cierto para el campo de la historieta, sin embargo, hoy tengo la impresión de que el humor gráfico ha retrocedido algunos pasos, en términos de valor. No solo en Rumania, sino en todo el mundo. Se puede ver en las competencias internacionales que ya no tienen el mismo nivel de seriedad, quizás porque hay mucha superficialidad por parte de organizadores y jurados. Parece que el nivel de calidad ha bajado».

¿Hay museos del humor en Rumanía? "No. En Timisoara, Stefan Popa Popas ha creado su propio Museo de la Historieta, donde quiere demostrar que es el mejor dibujante del planeta".

Pero en Rumanía hay muchos caricaturistas, dibujantes e incluso escuelas de humor gráfico. «Sí, y eso me enorgullece mucho. Hay una gran cantidad de diseñadores, y muy apreciados en el mundo como Mihai Ignat, Constantin Ciosi, Mihai Stanescu, Doru Axinte, Gabriel Rusu, etc…»

Los antihéroes del humor

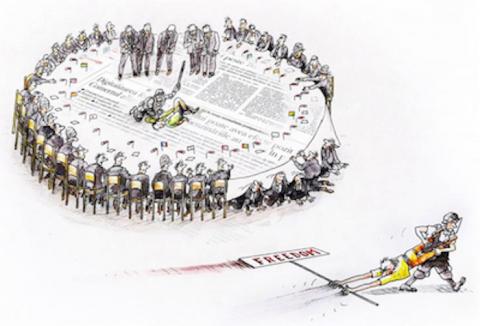

El cómico es una voz de la verdad, fantaseada en lo risible, a veces de manera mezquina o contundente, a veces filosóficamente, pero siempre preferentemente en una expresión sencilla. El pueblo, amante de lo risible como exabrupto, como terapia conductual, siempre ha tenido sus protagonistas, casi siempre anónimos, en la creatividad, para huir mejor de la censura y la opresión, como antihéroes en la lucha por el derecho a reír, o en menos para sonreír en cómplice de la revuelta. Si en realidad la gran mayoría nunca pasa a la historia, unos pocos acabaron convirtiéndose en leyendas mitificadas en tradiciones de risa popular, voces de la filosofía popular con historias reales y otros acoplados posteriormente de forma anónima a lo largo de los siglos.

Aquí ya he hablado de uno de esos antihéroes del humor, el sufí Nasreddin Hoca que puebla el imaginario de los pueblos subyugados por el antiguo Imperio Otomano, pero también podemos invocar a otros personajes de toda Europa que no sólo enriquecen el folclore, sino que moldean , sintetizar la esencia humorística de ese pueblo o región.

La idiosincrasia de cada uno de ellos es casi siempre la misma, la del "loco del pueblo", "el tonto del pueblo", "el santo loco" que dice las verdades sin saberlo, por tanto cómico, que grita que "el rey se vaya desnudo", viendo más allá que todas las demás mentes y ojos "sanos". En Portugal no tenemos ninguno de estos antihéroes, pero en los Países Bajos (Bélgica y Holanda) encontramos dos personajes interesantes. Uno no es más que una simple escultura de 61 cm, creada en el siglo XIX. XV como fuente – el Mennenken Piss (el niño meando) que representa la independencia de espíritu de los bruselenses. Luego tenemos a Till Eulenspiegel, un personaje que nació en el siglo XIV y que se convertiría en un símbolo de la revuelta flamenca/holandesa. Es un niño travieso que suele utilizar la escatología, es decir, el humor vulgar para ridiculizar los poderes, así como los vicios humanos.

Sin embargo, es en Europa del Este donde estos personajes cobrarán más vida en el folclore local. Por ejemplo, en el antiguo reino de Polonia (territorio que ahora es Ucrania), los judíos crearon en el siglo XVIII el mito de Hershel de Ostropol, un personaje lúdico que con sus bromas y travesuras ridiculizaba a los ricos y poderosos. Se trata de una figura inspirada en una persona real, que llegó a servir como bufón en la corte del rabino Boruch, lo que sería la causa de su muerte por reacción a la censura.

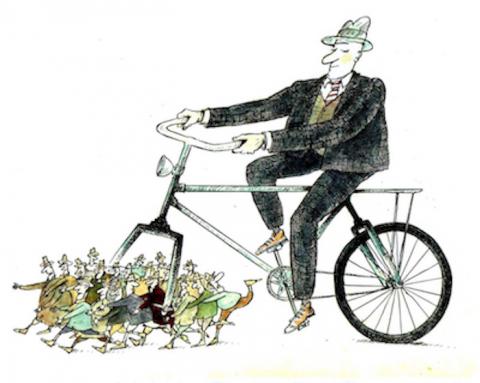

En los territorios que fueron dominados por los otomanos, tenemos tres personajes astutos, irreverentes, lo que llamaríamos astucia paleto que logran engañar a los engreídos, a los orgullosos. Entonces, en Rumania tenemos el Păcală (que significa engañar), un campesino irreverente, un bufón de pueblo que ridiculiza el poder: el sacerdote, el boyardo o el juez. El búlgaro Hitar Petar (también reclamado por los macedonios como Itar Pejo) es el mismo tipo de campesino astuto que, careciendo del lado filosófico de Nasreddin, divierte al pueblo como su antihéroe contra la opresión otomana, contra el poder establecido.

El húngaro Csalóka Peter, por su parte, es un personaje de los cuentos de hadas que luego pasó al teatro popular, encarnando los sueños incumplidos de los pobres, es decir, la victoria de la astucia ante jueces y gobernantes.

Muchos otros antihéroes humorísticos existirán por toda Europa, destacando uno que, a pesar de no tener orígenes populares, antes de la literatura -Don Quijote de la Mancha- es la máxima expresión del humor hecho un carácter crítico y pedagógico.

Romania is the country better known for the terror of Count Dracula than for its humor, however in the context of international graphic humor contests it has a strong presence of participants and winners, that's why I invited the already awarded in Portugal, Constantin Pavel to tell us about the state of mind of their country. «Romanian people use humor to “laugh at problems” and the justification could be the fact that throughout history we have always had many problems. Only, after getting acquainted with the humor of other peoples, I understood that Romanians do not have copyright on this principle. There are many other places in the world where they also laugh this way and I have to say that I think that's why they say that the language of humor is universal. Everyone laughs the same way and the mechanisms are the same everywhere."

But is there really nothing different? “About 44% of the Romanian population lives in rural areas. The European Union average is 25%. For this reason, Romanian humor bears the imprint of that rurality, a popular and peasant humor, a healthy and lively humor, refined over hundreds of years. The origin of our people is Dacian-Roman. The Roman Empire managed to conquer many territories, subjugating much of Europe today, but the conquests did not stop here, continuing in Africa and even in Asia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Babylonia... taking away Romanians and bringing cultures and that made Romanians have a lot of humor inherited from those who emigrated and who have the impression that they conquered the world.

The Ottoman influence brought new characters and situations to Romanian culture. A well-known descendant of the fanariot world is the character Nastratin Hogea, created by Anton Pann (1790/1854) (inspired by the Sufi Nasreddin Hoca). This folklorist, poet, musician was known for his parables full of humor and wisdom, jokes about gypsies, an ethnic minority. The main themes are theft, the refusal to work, many children; in essence, all the negative stereotypes about the Roma in Romania. These stereotypes of gypsies or gypsies denounced in the century. XIX are still valid. They are one of the largest ethnic minority groups in Romania (3% of the total population). His humor is very natural, the result of his close relationship with nature and reality. Simple and authentic, devoid of the lies of the civilized world, it reflects the ancestral humor of antiquity.

Romanian humor is more evolved, developed in another civilization stage and with refined aspects and conditions of communism. For example, before the Revolution it was not easy to be a comedian. There was communist censorship and great care had to be taken so that subversive and anti-communist messages, considered dangerous for the regime, did not appear in the public space. But, on the other hand, he had a creative advantage. Comedians were forced to seek subtle, hidden, much more intelligent and sophisticated means of expression to evade censorship and reach the public. This permanent exercise, for years, improved the quality of Romanian humor."

This humor, in what genre of artistic expression is it best expressed? "In all of them. It is difficult to choose just one. For example, in letters I cannot fail to mention George Topîrceau, Ion Creangâ, Vlad Musatescu... or the playwrights Ion Luca Caragiale, Constantin Tanase and Tudor Musatescu, who became true icons of Romanian humor and spirit.

Alongside them, there is a gallery of very important actors: Puiu Călinescu, Jean Constantin, Amza Pellea, Toma Caragiu, Dem Rădulescu, Ștefan Bănică and Stela Popescu.

All this is also true for the field of comics, however, today I have the impression that graphic humor has taken a few steps back, in terms of value. Not only in Romania, but all over the world. It can be seen in international competitions that they no longer have the same level of seriousness, perhaps because there is a lot of superficiality on the part of organizers and juries. It seems that the quality level has gone down.

Are there humor museums in Romania? "No. In Timisoara, Stefan Popa Popas has created his own Cartoon Museum, where he wants to prove that he is the best cartoonist on the planet."

But in Romania there are many caricaturists, cartoonists and even schools of graphic humor. Yes, and that makes me very proud. There are a large number of designers, and highly appreciated in the world such as Mihai Ignat, Constantin Ciosi, Mihai Stanescu, Doru Axinte, Gabriel Rusu, etc…»

The antiheroes of humor

The comedian is a voice of truth, fantasized in the laughable, sometimes meanly or bluntly, sometimes philosophically, but always preferably in a simple expression. The people, lovers of the laughable as an outburst, as behavioral therapy, have always had their protagonists, almost always anonymous, in creativity, to better escape censorship and oppression, as anti-heroes in the fight for the right to laugh, or in less to smile in accomplice of the revolt. If in reality the vast majority never go down in history, a few ended up becoming mythologized legends in popular laughter traditions, voices of popular philosophy with true stories and others later coupled anonymously over the centuries.

Here I have already spoken about one of those humorous anti-heroes, the Sufi Nasreddin Hoca who populates the imagination of the peoples subjugated by the former Ottoman Empire, but we can also invoke other characters from all over Europe who not only enrich folklore, but also shape , synthesize the humorous essence of that town or region.

The idiosyncrasies of each one of them is almost always the same, that of the "fool of the people", "the fool of the people", "the holy fool" who tells the truth without knowing it, therefore comic, who shouts that "the king go naked", seeing further than all other "sound" minds and eyes. In Portugal we don't have any of these anti-heroes, but in the Netherlands (Belgium and Holland) we find two interesting characters. One is nothing more than a simple 61 cm sculpture, created in the 19th century. XV as a fountain – the Mennenken Piss (the pissing boy) which represents the independence of spirit of the Brussels people. Then we have Till Eulenspiegel, a character who was born in the 14th century and who would become a symbol of the Flemish/Dutch revolt. He is a mischievous child who often uses eschatology, that is, vulgar humor to ridicule powers, as well as human vices.

However, it is in Eastern Europe where these characters will come to life in local folklore. For example, in the former kingdom of Poland (a territory that is now Ukraine), Jews in the 18th century created the myth of Hershel of Ostropol, a playful character who ridiculed the rich and powerful with his pranks and pranks. It is a figure inspired by a real person, who came to serve as a jester in the court of Rabbi Boruch, which would be the cause of his death due to reaction to censorship.

n the territories that were dominated by the Ottomans, we have three cunning, irreverent characters, what we would call redneck cunning who manage to deceive the conceited, the proud. So, in Romania we have the Păcală (which means to deceive), an irreverent peasant, a village jester who ridicules power: the priest, the boyar or the judge. The Bulgarian Hitar Petar (also claimed by the Macedonians as Itar Pejo) is the same kind of cunning peasant who, lacking Nasreddin's philosophical side, amuses the people as their anti-hero against Ottoman oppression, against the establishment.

The Hungarian Csalóka Peter, for his part, is a character from fairy tales who later went on to popular theater, embodying the unfulfilled dreams of the poor, that is, the victory of cunning before judges and rulers.

Many other humorous anti-heroes will exist throughout Europe, highlighting one that, despite not having popular origins, before literature -Don Quixote de la Mancha- is the maximum ]