Siro es uno de los artistas e investigadores del humor más reconocidos de Galicia. Nacido en Ferrol (1943), inició su actividad periodística en 1970 en la revista Chan, pasando por Ferrol Diario, El Ideal Gallego, La Región, El Norte de Galicia, Grial, Teima, Vagalume, Can sen Dono, Encrucillada, Diario 16... pero sería fundamentalmente en La Voz de Galicia donde más centraría su trabajo desde 1985 hasta la actualidad (a pesar de haberse jubilado en 2006).

Su obra no sólo vive de dibujos y crónicas de prensa, ya que ilustró numerosos libros de otros autores, como trabajos de medallas, cerámica, pintura, creó la Plaza del Humor en La Coruña, ayudó a Xaquin Marín en la creación del Museo del Humor de Fene fue guionista, director y locutor de programas de radio y televisión, destacando entre estas series de humor el programa "Corre Carmela, que chove" (1993/2014).

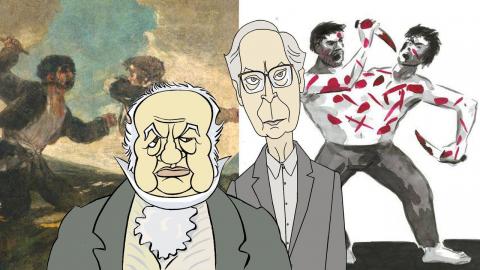

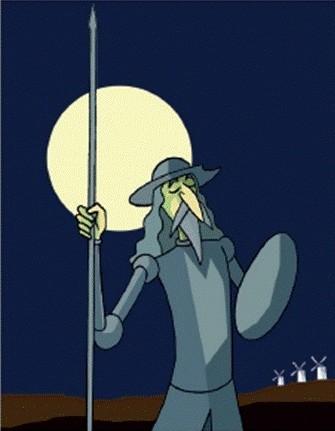

En la investigación teórica hay varios títulos importantes, de los que destaco «Castelao en el Arte Europeo» o «Cervantes y el Quijote. La invención del humorismo»..

Pasemos a la entrevista a este artista octogenario siempre activo y creativo.

OMS - Si es cierto que el primer problema del avance de la edad corporal es la visión y el poder de las manos firmes, la creatividad, disfrazados de ismos, como puntilismos, expresionismos, impresionismos, cubismos, futurismos... superar estos handicaps con el tiempo, con nuevas técnicas, con instrumentos alternativos recreando el rasgo personal? Es decir, la mano tiembla, los ojos fallan, pero el estado de ánimo persiste, ¿o no?

Siro - En mi caso, con 81 años, mi deterioro físico no afecta a mi trabajo de dibujante en ninguno de los géneros que practico, incluidos el humor gráfico y la caricatura. Después de operarme de cataratas y miopía veo algo peor de cerca, pero conservo el pulso y el trazo de la juventud. Tampoco me afectan las nuevas tecnologías que permiten dibujar con programas de ordenador porque las ignoro y sólo uso el photoshop. Para mí el placer de dibujar empieza al coger el lápiz de grafito y el papel en blanco. Nada tengo contra los programas para dibujar, pero no son para mí y creo que tampoco lo serían si tuviese 30 años. Sin embargo me encanta el I´pad porque me permite dibujar comodamente mientras veo la tele y en fecha próxima publicaré un libro de caricaturas de Valle Inclán hechas así, con un ojo en la pantalla del televisor y el otro en la del I´pad.

Respecto al estado de ánimo, estoy tan interesado en crear arte y humor como el día que publiqué mis primeros dibujos. Con las ideas más claras y lamentando no poder empezar de nuevo con la experiencia adquirida. Lo dice el refrán y dice bien: <Sabe más el diablo por viejo que por diablo>.

OMS - ¿El envejecimiento tabién daña la visión filosófica del humor, haciéndolo avinagrado? Con la edad, con el peso de haber vivido, existido, criticado repetidamente… ¿la mirada se vuelve más satírica o irónica?

Siro - ¡Que va! En absoluto. Hombre, no sé cómo seré si me veo tan decrépito que no desee vivir; pero ahora, pese a los achaques que tengo, mi sentido del humor no ha meguado e incluso puede que sea mayor. Es verdad que la sociedad cambia y que muchos de esos cambios me molestan y me duelen, pero también sé que cada generación crea su propia cultura y entiendo que soy un convidado en su tiempo, así que yo a lo mío y ellos a lo suyo.

Nada de lo que no me gusta me avinagra, ni me hace más satírico. Publico en las páginas de Opinión del periódico La Voz de Galicia una sección que titulo Puntadas sen fío porque no soy nada pretencioso y con él pido a mis lectores que no me tomen demasiado en serio, ni demasiado en broma; como Julio Camba había pedido a los suyos hace muchos años.

OMS - Por supuesto, hay grandes diferencias en la sociedad, en los países, en las influencias geopolíticas y esto siempre influye en la visión del artista, por lo que es redundante preguntar si hay diferencias entre su estado de ánimo cuando comenzó y ahora, pero puede explicar cuál es en ¿diferente?

Siro - Cuando empecé a publicar humor gráfico y caricatura, en 1969, no tenía idea de lo que hacía, ni de lo que debería hacer. No tenía un estilo y lo único claro era que los textos deberían ir en gallego. Hace mucho tiempo aclaré mis ideas y sé que debo escribir en gallego y también dibujar en gallego. En cuanto a mi estado de ánimo, ante lo que me contraría, lo expliqué en la respuesta anterior.

OMS - Toda su vida, otros esperan que un humorista sea una persona alegre y divertida. Con la edad, ¿siguen pidiendo lo mismo o aceptan que también pueden hacer vinagre? ¿O un cómico ha sido siempre un avinagrado como dispensador de sonrisas cómplices?

Siro - El humorista es como el zapatero, el comerciante o el perito agrónomo. Los hay encantadores y los hay insoportables. Yo he conocido a algunos que eran graciosos el día entero y a otros tímidos y tristes, que no abrían la boca más que para comer y beber. Los he conocido abstemios y borrachos perdidos... Los que trato hoy, de mi edad e incluso mayores, no son avinagrados, pero alguno habrá y estará tan cabreado que ni saldrá de casa.

Es verdad que hay <humoristas moralistas> con alma de inquisidor y de verdugo, que atacan ferozmente a la <sociedad corrompida>. Son personas que tienen poco o nada de humoristas aunque puedan hacer una obra satírica espléndida. Es el caso del francés Forain, muy conservador, muy reaccionario, pero muy grande como dibujante y en sus críticas a la sociedad cambiante, que él no aceptaba. Suelen ser individuos avinagrados desde que tomaron el primer biberón. El verdadero humorista –del que Cervantes es arquetipo- no es avinagrado aunque sufra la injusticia y la combata con sus viñetas. El tercer tipo entre los creadores de humor, el cómico, el que procura la carcajada de sus seguidores, raramente trata temas cabreantes y si lo hace los enfoca desde el absurdo o el ridículo. No hay inteligencia completamente feliz, así que para reír es mejor quedarse en la superficie de las cosas. En lo aparente, en lo divertido.

OMS - ¿Qué es más difícil de aceptar a medida que envejeces? ¿Se necesita más esfuerzo para mantener el humor todos los días, o ya no es una fortaleza, sino una debilidad? ¿Te sientes envejecido? ¿Qué es para ti la vejez?

Siro - Yo soy un viejo feliz, no sé si por mi sentido del humor o por mi evidente inconsciencia e irresponsabilidad ante mis problemas de salud. En los tres últimos años me salvé de varios infartos, de un ictus, y durante el 2022 descubrí que tengo cáncer de piel y tuve que ser operado de dos tumores en la cabeza, con un post operatorio complicadísimo. Dos veces por semana acudí al hospital durante ocho meses para hacer las curas de una herida que no cerraba e incluso crecía. Nada de eso me afectó anímicamente. Creo que soy un estoico y me alegro de ello.

Sí me siento envejecido y desde mi experiencia te digo que la vejez es bajar de una acera y notar que te tiembla el esqueleto todo; es perder la voz con la que enamoraba a las señoras en mis programas de radio; es tener que pararme en el camino para coger aliento al subir una cuesta mínima..., pero también es ver más allá del horizonte, entender el presente con el conocimiento del pasado; es saciar mi curiosisdad en Google, que vale más que la Biblioteca de Alejandría; es escribir libros que no existen... En definitiva, la vejez es vivir con la ilusión de la juventud, sabiendo que cada día es un regalo que agradecer y disfrutar.

OMS - Al mirar al pasado, ¿es importante mantener vivos los momentos más humorísticos, relegando las tragedias al olvido o tienen más fuerza y destruyen los mejores momentos de la vida?

Siro - Las tragedias no se pueden o no se deben olvidar. La Guerra Civil española fue una tragedia que tengo muy presente, entre otras razones porque yo soy consecuencia de ella. Mi padre fue encarcelado en 1937, salió en 1941, pasó parte del 1942 tuberculoso y en enero de 1943 nací yo. Gente del Régimen me recordó durante mi adolescencia que yo había perdido una guerra en la que no había participado y crecí con la mentalidad del vencido, odiando a Franco y a todos los franquistas. A los treinta años ya sabía que también una parte de los franquistas habían sufrido la barbarie de republicanos fanáticos y desalmados, por lo que no podía odiar así y mi odio debía ser selectivo; dirigido a personas concretas con nombres y apellidos. Hoy escribo en el periódico sobre la tragedia de la Guerra Civil desde esa perspectiva y valoro lo que la Transición supuso para superar el odio entre los españoles, y desde luego no entiendo el sectarismo, el maniqueismo y el fanatismo de quienes se empeñan en ver la Guerra Civil como un enfrentamiento entre buenos y malos, y a los adictos –a todos los adictos al Régimen- como unos canallas. Y menos a los <militarotes franquistas jubiletas> que quieren <cargarse> a 26 millones de rojos hijos de puta.

Claro que prefiero tratar en mis dibujos temas de actualidad y hacerlo con honestidad, con la honestidad exigible a todo periodista, a todo creador de opinión; pero tan escasa. Es algo que me propuse hace muchos años, cuando fui consciente de mi responsabilidad, y puedo decir que después de una vida profesional dedicada a la caricatura política; después de haber contado con viñetas los caminos a la Constitución y a la Autonomía Gallega, tengo tantos amigos en la derecha como en la izquierda, aunque soy de izquierdas y no lo oculto. Respeto demasiado el periodismo y la caricatura política para convertirme en <periodista de partido>.

OMS - ¿Es más fácil mirar la vejez de los demás que tu propia "decadencia" física?

Siro - Creo que no. Yo me miro al espejo del ascensor y, como me veo todos los días, no soy muy consciente de mi decrepitud. Incluso me veo un viejo guapo. En cambio, me encuentro con amigos a los que no veo desde hace tiempo y, salvo agunos que parecen haber hecho un pacto con el diablo, los veo cascadísimos. Ellos pensarán lo mismo de mí, lógicamente. Además hay gente que envejece bien y quien envejece mal. Personas que están mejor como viejos que como estuvieron de jóvenes, y al revés. Pero eso importa poco. A los 80 años lo importante es saber colocarnos para no mear los zapatos.

OMS - ¿Qué le preocupa más, la falta de memoria o los problemas físicos?

Siro - Depende de la pérdida en cada caso. Para los fallos de memoria leves hay agendas y calendarios de mesa; para los graves, para el alzheimer, la solución es morirse. Para problemas físicos como los míos, está el humor; para las enfermedades degenerativas lo mejor es morirse a tiempo.

No pienso en esas cosas, pero creo esto que digo.

OMS - Cuando haces humor como afición, en el retiro sigue siendo un escape. Si eres profesional desde hace décadas, la jubilación, en principio, es finalmente descansar, pero con humor, ¿no echas de menos este ejercicio constante de mirar la vida al revés? ¿Se abandona por completo o se convierte en un pasatiempo de entretenimiento?

Siro - Cuando me jubilé dejé la caricatura política y el dibujo de humor, pero me dediqué a escribir libros y a hacer exposiciones de dibujo y pintura, que nada tienen con el humor. Me gustaría volver al humor gráfico en una viñeta diaria, pero no tengo tiempo. De todas formas, mi jubilación es teórica porque en los últimos quince años hice ilustración, retrato, cartelismo, dibujo expresionista... Y en eso sigo. El dibujo para mí es mucho más que un entretenimiento. Es una necesidad imperiosa.

OMS - ¿Cómo fue la adaptación a las nuevas tecnologías? La velocidad del cambio ha sido vertiginosa, lo que por un lado ha facilitado ciertos trámites técnicos, también ha complicado a los que no les gustaba el cambio. ¿Cómo te pasó a ti? ¿Sigues prefiriendo las técnicas clásicas?

Siro - He respondido esta pregunta en un comentario anterior, pero te confirmo que prefiero las técnicas clásicas y que no tengo el menor interés en conocer las nuevas tecnologías. En este momento estoy haciendo el cartel del Día da Ilustración de 2023 y lo hago de forma que quede clarísimo que yo prefiero lápiz, papel y tinta china. Todos los anteriores fueron hechos con ordenador y están muy bien, pero no van por ahí mis gustos y preferencias.

OMS - Básicamente, son muchos años de testigo de cambios en la sociedad, en el comportamiento político y social, además de los técnicos, es decir, no solo eres parte de la historia sino también cronista de esa misma historia. ¿Qué más ha cambiado? ¿Cómo ves esta evolución, principalmente en la actividad del dibujante (comediante)?

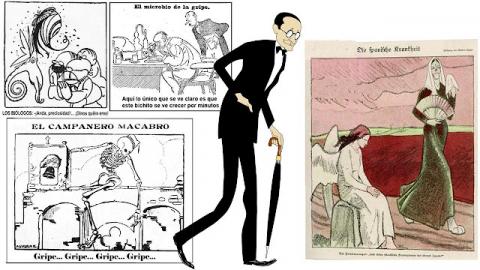

Siro - Cuando yo empecé a hacer humor gráfico y caricatura tenía que saber torear a la censura y resignarme a que no se pudiesen publicar las caricaturas que le hacía a Franco. Incluso al comienzo de la Transición, en 1977, fui juzgado dos veces por un tribunal civil y se me abrió un consejo de guerra en el que se me pedían seis años y un día por el delito de <sedición e incitación a la misma>. Después, el director de La Voz de Galicia me puso a hacer caricatura política y conté la historia de la Autonomía Galega hasta el año 2006 en que me jubilé. Fueron miles de dibujos, de los que doné los 2600 más importantes al Parlamento de Galicia.

Me siento afortunado por haber sufrido la dictadura, vivido la ilusión de la Transición, y comentarlas en mis viñetas. Fui un privilegiado. Hoy el ambiente de crispación en España recuerda el de los años anteriores a la Guerra Civil y es muy preocupante; pero también tiene interés para el humorista gráfico que actúe como cronista y yo podría tratarlo con trazos como lo hago con palabras en mis artículos de opinión. Hay quien lo hace y muy bien en varios medios.

OMS - Las tecnologías cambian, el humor es el mismo, pero la sociedad ha cambiado y ha puesto otras trabas más complicadas a la libertad del humor. ¿Hay tanta o más libertad creativa hoy que antes? La corrección política, más las susceptibilidades idiotas de pequeños grupos, tribus, clubes, partidos… ¿no hizo más presente la censura en las obras publicadas?

Siro - Creo que estamos viviendo un tiempo de pobreza cultural, en tendiendo la cultura en el sentido más amplio. El deterioro del idioma en TV y radio; las faltas de ortografía en los periódicos; el arte conceptual que de arte no tiene más que el nombre; la moda como pitorreoo de los diseñadores, conscientes de que todo vale y que los pantalones rotos o con la potra en la rodilla tendrán éxito; la pérdida de las normas de urbanidad, la falta de respeto al contrario, los análisis simplistas de la realidad social, el enfrentamiento feroz entre derechas e izquierdas y entre el nacionalismo español y los nacionalismos periféricos... Es el ambiente idóneo para que los torpes se conviertan en protagonistas. Nunca las masas, temidas por Ortega y Gasset, fueron tan masas como hoy y contra ellas no hay censura que valga porque la inteligencia, las buenas maneras y el buen gusto son valores <burgueses> qiue los torpes desprecian.

OMS - ¿Cómo ve la sociedad en la que vives a las personas mayores?

Siro - Yo me siento muy querido y excesivamente valorado por la gente que me conoce y me sigue en prensa. Cada vez hay más gente que me pide prólogos, reseñas, presentaciones e ilustraciones de libros. Será que piensan que cualquier día <espicho>, pero lo cierto es que nunca estuve tan solicitado. En cuanto a los viejos en general, creo que para las familias tradicionales son importantes y los cuidan y miman. El problema surge cuando el anciano pierde la chaveta y es necesario internarlo, porque las residencias que garantizan la atención y el buen trato están al alcance de muy pocas familias. Ése es un problemia serio. La vida de los viejos es, en muchos casos, una tragedia.

OMS - ¿Qué es para ti el humor y cuál es su importancia en la sociedad?

Siro - El humor es para mí una filosofía de vida, perfectamente asumida. Salvo la tragedia, yo no sé ver nada sin la lente del humor. Wenceslao Fernández Flórez, gran humorista gallego, publicó un libro de relatos humorísticos y lo tituló Las gafas del diablo, que escandalizó a los que ven pecados por todas partes y nunca sonríen porque no saben. Yo tengo unas gafas así, pero dentro del cerebro.

OMS - ¿Es la demencia senil una variante del humor absurdo?

Siro - ¡No, que va! No hay relación entre una y otro. El humor es una creación y la demencia senil, aunque en momentos pueda hacer gracia, es una enfermedad terrible.

OMS - ¿Cree que el humor puede ayudar a las personas a aceptar mejor el envejecimiento y contribuir al optimismo cotidiano del decaimiento físico?

Siro - A mí me ayuda. Y mucho, muchísimo. No veas cómo me río cuando intento, inútilmente, ponerme los pantalones de pie y atarme los cordones de los zapatos. Reirse de uno mismo es muy sano.

OMS - ¿Puede el deterioro mental ser contrarrestado por la creatividad humorística? Es decir, si son 12 anécdotas, el resto ya son variaciones en la Biblia, ¿hay una tendencia con la edad a recuperar viejas ideas, tratando de hacer nuevas variaciones, tratando de mejorarlas? ¿Es importante reciclar en el humor?

Siro - Si el deterioro mental es leve y quien lo padece tiene suficiente sentido del humor, puede reirse de sí mismo, como se ríe el sordo cuando entiende mal una pregunta y responde algo disparatado. Eso es beneficioso para él y para su familia y amigos. Si el deterioro mental es grave, pero el enfermo es feliz, puede darse también esta situación positiva. Mi hermana, 17 años mayor que yo, padeció alzheimer los últimos años de vida. Cuando yo iba a visitarla, tenía una gran alegría: -¡ Meu irmanciño! –decía y me abrazaba. Si yo me ausentaba un minuto para ir al coche o hablar con alguien, en cuanto volvía a entrar se repetía la escena con el <meu irmanciño> y el abrazo. Nos reíamos todos y también ella, sin saber por qué.

OMS - En la vejez, ¿qué es más divertido para jugar o advertir a los demás? ¿Problemas físicos, mentales, sociales o políticos?

Siro - Los problemas nunca son divertidos para quien los padece, pero es verdad que el sentido del humor puede suavizarlos y hasta hacerlos risibles. Dentro de unos límites, claro, porque hay problemas que no pueden divertir a nadie. El hambre en nuestra sociedad no tiene gracia la mires por donde la mires. En la ficción sí, y ahí está Chaplin convirtiendo la de Charlot en una escena genial de La quimera del oro. Hay otros ejemplos en la literatura, empezando por la novela picaresca; pero una cosa es la ficción y otra la vida real. De los problemas físicos y mentales ya he opinado en respuestas anteriores.

OMS - ¿Es más fácil, o más difícil, que una persona mayor mire el futuro con humor?

Siro - No lo sé. Yo viajo montado sobre el humor pero veo el futuro con preocupación. No por mí, que estoy en la línea de meta; pero veo un mundo loco, dispuesto a repetir las barbaridades del pasado. Si decidiese reproducir en imágenes lo que la realidad me inspira, haría una serie de viñetas con otra Nave de los locos en portada y dentro una selección de imágenes satíricas, como las que hice en 1977 sobre los Pecados Capitales. Sería un libro negro, esperpéntico, como el futuro que veo.

OMS - ¿Te asusta la muerte o es morirse de risa la mejor manera de cerrar este ciclo?

Siro - No me asusta y quiero verla llegar y recibirla costesmente. Dialogar con ella un rato y después irnos juntos, en amor y compañía. Mi próximo libro se titulará A puta morte, porque se llevó a todos los amigos de quienes hablo; pero en la introducción explico que no tengo nada contra ella, que es una mandada. Recientemente hice el prólogo de la segunda edición del libro Paseata arredor da morte, del antropólogo gallego Domingo García-Sabell, muerto en 2003, y lo hice con humor. Muchos lectores creen que es lo mejor que escribí en toda mi vida y yo lo creo posible.

OMS - ¿Está preocupado por el futuro de su trabajo después de que se haya ido?

Siro - No, porque hice donación de 2600 caricaturas as Parlamento de Galicia, un par de cientos a la Biblioteca Nacional y una colección de retratos y caricaturas de Valle Inclán al Museo de A Pobra do Caramiñal. Lo que quede no será un incordio para mis descendientes, y si lo es que hagan lote y lo salden.

Growing Old with Humor – Siro Lopez (Spain)

By Osvaldo Macedo de Sousa

Siro is one of the most recognized humor artists and researchers in Galicia. Born in Ferrol (1943), he began his journalistic activity in 1970 in the magazine "Chan", passing through Ferrol Diario, El Ideal Gallego, La Región, El Norte de Galicia, Grial, Teima, Vagalume, Can sen Dono, Encrucillada, Diario 16... but it would be primarily in La Voz de Galicia where he would focus his work most from 1985 to the present (despite having retired in 2006).

His work not only lives on drawings and press reports, since he illustrated numerous books by other authors, such as works of medals, ceramics, painting, he created the Plaza del Humor in La Coruña, he helped Xaquin Marín in the creation of the Museum of Humor de Fene was a scriptwriter, director and host of radio and television programs, highlighting among these comedy series the program "Corre Carmela, que chove" (1993/2014)..

In theoretical research there are several important titles, of which I highlight "Castelao in European Art" or "Cervantes and Don Quixote. The invention of humor".

Let's move on to the interview with this octogenarian artist who is always active and creative.

OMS - If it is true that the first problem of advancing body age is the vision and the power of firm hands, creativity, disguised as isms, such as pointilism, expressionism, impressionism, cubism, futurism... overcoming these handicaps with time, with new techniques, with alternative instruments recreating the personal trait? That is, the hand shakes, the eyes fail, but the mood persists, doesn't it?

Siro - In my case, at 81 years old, my physical deterioration does not affect my work as a cartoonist in any of the genres I practice, including graphic humor and caricature. After having cataract and myopia surgery, I see something worse up close, but I retain the pulse and lines of youth. I am also not affected by new technologies that allow drawing with computer programs because I ignore them and only use Photoshop. For me, the pleasure of drawing begins when I pick up the graphite pencil and blank paper. I have nothing against drawing programs, but they are not for me and I think they would not be if I were 30 years old. However, I love the I'pad because it allows me to draw comfortably while watching TV and soon I will publish a book of Valle Inclán caricatures done like this, with one eye on the television screen and the other on the I'pad.

Regarding humor, I am as interested in creating art and humor as the day I published my first drawings. With clearer ideas and regretting not being able to start again with the experience acquired. The saying goes and it says well: <The devil knows more because he is old than because he is a devil>.

OMS - Does aging also damage the philosophical vision of humor, making it sour? With age, with the weight of having lived, existed, criticized repeatedly... does the look become more satirical or ironic?

Siro - What's up! Absolutely. Man, I don't know what I'll be like if I look so decrepit that I don't want to live; but now, despite the ailments I have, my sense of humor has not diminished and may even be greater. It is true that society changes and that many of these changes bother me and hurt me, but I also know that each generation creates its own culture and I understand that I am a guest in their time, so I do mine and they do theirs.

Nothing I don't like makes me sour or makes me more satirical. I publish in the Opinion pages of the newspaper La Voz de Galicia a section that I title Puntadas sen fío because I am not at all pretentious and with it I ask my readers not to take me too seriously, nor too jokingly; as Julio Camba had asked of his people many years ago.

OMS - Of course, there are big differences in society, in countries, in geopolitical influences and this always influences the vision of the artist, so it is redundant to ask if there are differences between his state of mind when he started and now, but Can you explain what is different?

Siro - When I started publishing graphic humor and cartoons, in 1969, I had no idea what I was doing, or what I should do. It did not have a style and the only thing clear was that the texts should be in Galician. A long time ago I clarified my ideas and I know that I should write in Galician and also draw in Galician. As for my state of mind, what bothered me, I explained it in the previous answer.

OMS - All their lives, others expect a humorist to be a happy, funny person. As you get older, do you still ask for the same thing or do you accept that you can also make vinegar? Or has a comedian always been sour as a dispenser of knowing smiles?

Siro - The humorist is like the shoemaker, the merchant or the agronomist. There are charming ones and there are unbearable ones. I have known some who were funny all day long and others who were shy and sad, who only opened their mouths to eat and drink. I have known them to be teetotalers and hopeless drunks... The ones I deal with today, my age and even older, are not sour, but there will be some who will be so angry that they will not even leave the house.

It is true that there are <moralistic humorists> with the soul of an inquisitor and an executioner, who fiercely attack the <corrupt society>. They are people who have little or no humor even though they can make a splendid satirical work. This is the case of the Frenchman Forain, very conservative, very reactionary, but very great as a cartoonist and in his criticism of the changing society, which he did not accept. They tend to be sour individuals since they took the first bottle. The true humorist – of which Cervantes is the archetype – is not sour even if he suffers from injustice and fights it with his cartoons. The third type among humor creators, the comedian, the one who makes his followers laugh, rarely deals with angry topics and if he does, he approaches them from the absurd or the ridiculous. There is no completely happy intelligence, so to laugh it is better to stay on the surface of things. In the apparent, in the fun.

OMS - What is harder to accept as you get older? Does it take more effort to maintain your humor every day, or is it no longer a strength, but a weakness? Do you feel aged? What does old age mean to you?

Siro - I am a happy old man, I don't know if because of my sense of humor or because of my obvious unconsciousness and irresponsibility in the face of my health problems. In the last three years I was saved from several heart attacks, a stroke, and during 2022 I discovered that I have skin cancer and I had to undergo surgery for two tumors in my head, with a very complicated post-operative period. Twice a week I went to the hospital for eight months to treat a wound that did not close and even grew. None of that affected me emotionally. I think I'm a stoic and I'm glad of it.

Yes, I feel old and from my experience I tell you that old age is getting off a sidewalk and noticing that your entire skeleton is shaking; It is losing the voice with which I made the ladies fall in love with me on my radio programs; It is having to stop on the road to catch my breath when climbing a slight slope..., but it is also seeing beyond the horizon, understanding the present with the knowledge of the past; It is to satisfy my curiosity in Google, which is worth more than the Library of Alexandria; It is writing books that do not exist... In short, old age is living with the illusion of youth, knowing that each day is a gift to be grateful for and enjoyed.

OMS - When looking at the past, is it important to keep the most humorous moments alive, relegating tragedies to oblivion, or do they have more force and destroy the best moments in life?

Siro - Tragedies cannot or should not be forgotten. The Spanish Civil War was a tragedy that I have very much in mind, among other reasons because I am a consequence of it. My father was imprisoned in 1937, he was released in 1941, he spent part of 1942 suffering from tuberculosis and in January 1943 I was born. People of the Regime reminded me during my adolescence that I had lost a war in which I had not participated and I grew up with the mentality of the defeated, hating Franco and all the Francoists. At the age of thirty I already knew that a part of the Francoists had also suffered the barbarism of fanatical and heartless republicans, so I could not hate like that and my hatred had to be selective; addressed to specific people with first and last names. Today I write in the newspaper about the tragedy of the Civil War from that perspective and I value what the Transition meant to overcome hatred among the Spanish, and I certainly do not understand the sectarianism, Manichaeism and fanaticism of those who insist on seeing the Civil War as a confrontation between good and bad, and the addicts – all addicts to the Regime – as scoundrels. And even less to the <retired Francoist militarists> who want to <kill> 26 million red sons of bitches.

Of course I prefer to deal with current issues in my drawings and do so with honesty, with the honesty required of every journalist, every creator of opinion; but so scarce. It is something that I proposed many years ago, when I was aware of my responsibility, and I can say that after a professional life dedicated to political cartooning; After having told in vignettes the paths to the Constitution and Galician Autonomy, I have as many friends on the right as on the left, although I am on the left and I do not hide it. I respect journalism and political caricature too much to become a <party journalist>.

OMS - Is it easier to look at the old age of others than your own physical "decay"?

Siro - I think not. I look in the elevator mirror and, as I see myself every day, I am not very aware of my decrepitude. I even look like a handsome old man. On the other hand, I meet friends I haven't seen for a long time and, except for a few who seem to have made a pact with the devil, I see them very broken. They will think the same about me, logically. Furthermore, there are people who age well and those who age poorly. People who are better off as old people than they were when they were young, and vice versa. But that matters little. At 80 years old, the important thing is to know how to position ourselves so as not to pee our shoes.

OMS - What worries you more, lack of memory or physical problems?

Siro - It depends on the loss in each case. For mild memory lapses there are agendas and desk calendars; For the serious ones, for Alzheimer's, the solution is to die. For physical problems like mine, there is humor; For degenerative diseases it is best to die on time.

I don't think about those things, but I believe what I say.

OMS - When you do humor as a hobby, in retirement it is still an escape. If you have been a professional for decades, retirement, in principle, is finally resting, but with humor, don't you miss this constant exercise of looking at life upside down? Is it abandoned completely or does it become an entertainment hobby?

Siro - When I retired I left political caricatures and humorous drawings, but I dedicated myself to writing books and holding drawing and painting exhibitions, which have nothing to do with humor. I would like to return to graphic humor in a daily cartoon, but I don't have time. In any case, my retirement is theoretical because in the last fifteen years I did illustration, portrait, poster design, expressionist drawing... And I'm still doing that. Drawing for me is much more than entertainment. It is an urgent need.

OMS - How was the adaptation to new technologies? The speed of change has been dizzying, which on the one hand has facilitated certain technical procedures, but has also complicated things for those who did not like the change. How did it happen to you? Do you still prefer classic techniques?

Siro - I have answered this question in a previous comment, but I confirm that I prefer classic techniques and that I have not the slightest interest in learning about new technologies. At this moment I am making the poster for Illustration Day of 1923 and I do it in a way that makes it very clear that I prefer pencil, paper and Indian ink. All the previous ones were made with a computer and are very good, but my tastes and preferences are not there.

OMS - Basically, there are many years of witnessing changes in society, in political and social behavior, in addition to the technical ones, that is, you are not only part of history but also a chronicler of that same history. What else has changed? How do you see this evolution, mainly in the activity of the cartoonist (comedian)?

Siro - When I started making graphic humor and caricatures I had to know how to fight the censorship and resign myself to the fact that the caricatures I made of Franco could not be published. Even at the beginning of the Transition, in 1977, I was tried twice by a civilian court and a court martial was opened against me in which I was asked for six years and one day for the crime of <sedition and incitement to it>. Later, the director of La Voz de Galicia had me do political cartoons and I told the story of the Galician Autonomy until 2006 when I retired. There were thousands of drawings, of which I donated the most important 2,600 to the Parliament of Galicia.

I feel lucky to have suffered the dictatorship, lived the illusion of the Transition, and commented on them in my cartoons. I was privileged. Today the atmosphere of tension in Spain is reminiscent of the years before the Civil War and is very worrying; but it is also of interest to the cartoonist who acts as a chronicler and I could treat it with strokes as I do with words in my opinion articles. There are those who do it and very well in various media.

OMS - Technologies change, humor is the same, but society has changed and has placed other, more complicated obstacles to the freedom of humor. Is there as much or more creative freedom today than before? Political correctness, plus the idiotic sensitivities of small groups, tribes, clubs, parties... didn't censorship make more present in published works?

Siro - I think we are living in a time of cultural poverty, in the broadest sense of culture. The deterioration of the language on TV and radio; spelling mistakes in newspapers; conceptual art that has nothing more than the name of art; fashion as the whistling of designers, aware that anything goes and that ripped pants or pants with a hole in the knee will be successful; the loss of the norms of civility, the lack of respect for the opposite, the simplistic analyzes of social reality, the fierce confrontation between right and left and between Spanish nationalism and peripheral nationalisms... It is the ideal environment for the clumsy become protagonists. Never have the masses, feared by Ortega y Gasset, been as massive as they are today and there is no censorship against them because intelligence, good manners and good taste are <bourgeois> values that the clumsy despise.

OMS - How does the society you live in view older people?

Siro - I feel very loved and excessively valued by the people who know me and follow me in the press. More and more people ask me for prologues, reviews, presentations and book illustrations. Maybe they think that any day <espicho>, but the truth is that I have never been so in demand. As for the elderly in general, I think that for traditional families they are important and they are cared for and pampered. The problem arises when the elderly person loses their temper and it is necessary to hospitalize them, because the residences that guarantee care and good treatment are available to very few families. That is a serious problem. The life of the elderly is, in many cases, a tragedy.

OMS - What is humor for you and what is its importance in society?

Siro - Humor is for me a philosophy of life, perfectly assumed. Except for tragedy, I don't know how to see anything without the lens of humor. Wenceslao Fernández Flórez, a great Galician comedian, published a book of humorous stories and titled it The Devil's Glasses, which scandalized those who see sins everywhere and never smile because they don't know. I have glasses like that, but inside the brain.

OMS - Is senile dementia a variant of absurd humor?

Siro - No, what's up! There is no relationship between one and the other. Humor is a creation and senile dementia, although it may be funny at times, is a terrible disease.

OMS - Do you think that humor can help people better accept aging and contribute to the daily optimism of physical decline?

Siro - It helps me. And very, very much. Don't see how I laugh when I try, in vain, to put on my pants and tie my shoelaces. Laughing at yourself is very healthy.

OMS - Can mental deterioration be counteracted by humorous creativity? That is, if there are 12 anecdotes, the rest are already variations in the Bible, is there a tendency with age to recover old ideas, trying to make new variations, trying to improve them? Is it important to recycle in humor?

Siro - If the mental deterioration is mild and the person suffering from it has a sufficient sense of humor, they can laugh at themselves, like the deaf person laughs when they misunderstand a question and answer something crazy. That is beneficial for him and his family and friends. If the mental deterioration is serious, but the patient is happy, this positive situation can also occur. My sister, 17 years older than me, suffered from Alzheimer's the last few years of her life. When I went to visit her, she was very happy: -Meu irmanciño! –he said and hugged me. If I left for a minute to go to the car or talk to someone, as soon as I came back in the scene was repeated with the <meu irmanciño> and the hug. We all laughed and so did she, without knowing why.

OMS - In old age, what is more fun to play or warn others? Physical, mental, social or political problems?

Siro - Problems are never fun for those who suffer from them, but it is true that a sense of humor can soften them and even make them laughable. Within limits, of course, because there are problems that cannot amuse anyone. Hunger in our society is not funny no matter how you look at it. In fiction yes, and there is Chaplin turning Charlot into a brilliant scene from The Gold Rush. There are other examples in literature, starting with the picaresque novel; But fiction is one thing and real life is another. I have already given my opinion on physical and mental problems in previous answers.

OMS - Is it easier, or more difficult, for an older person to look at the future with humor?

Siro - I don't know. I travel riding on humor but I see the future with concern. Not for me, I'm on the starting line; But I see a crazy world, ready to repeat the atrocities of the past. If I decided to reproduce in images what reality inspires me, I would make a series of vignettes with another Ship of Fools on the cover and inside a selection of satirical images, like the ones I made in 1977 about the Deadly Sins. It would be a black, grotesque book, like the future I see.

OMS - Are you afraid of death or is dying of laughter the best way to close this cycle?

Siro - It doesn't scare me and I want to see it arrive and receive it cost-effectively. Talk to her for a while and then leave together, in love and company. My next book will be titled A puta morte, because it took away all the friends I'm talking about; but in the introduction I explain that I have nothing against her, that she is an errand. I recently wrote the prologue to the second edition of the book Paseata arredor da morte, by the Galician anthropologist Domingo García-Sabell, who died in 2003, and I did it with humor. Many readers believe that it is the best thing I wrote in my entire life and I believe it is possible.

OMS - Are you worried about the future of your job after you're gone?

Siro - No, because I donated 2,600 caricatures to the Parliament of Galicia, a couple of hundred to the National Library and a collection of portraits and caricatures of Valle Inclán to the Museum of A Pobra do Caramiñal. What is left will not be a nuisance for my descendants, and if it is, let them make a batch and pay it off.