Para presentar al invitado que me honra tanto en este vis a vis, voy a a copiar un párrafo de uno de nuestros columnista de Humor Sapiens, el español Félix Caballero, al escribir sobre él:

“Xaquín Marín es un dibujante universal por haber colaborado en periódicos internacionales como los franceses “Le Telegramme”, y “Ouest-France”, el portugués “Trevim” o el mexicano “Norte”, y por haber participado en numerosos certámenes de humor gráfico a lo largo de todo el mundo, ganando en 1987 uno de los más importantes, el de Gabrovo (Bulgaria). Pero además ha sido jurado en algunos de ellos, como el PortoCartoon World Festival de Oporto (Portugal); el Salón Internacional de Humor de Piracicaba, en São Paulo (Brasil); y el World Press Cartoon de Lisboa. También porque tiene obra en unos 20 museos de humor de más de una decena de países de tres continentes, además de haber creado en 1984 el primero y mejor de la península ibérica, el de Fene, la localidad gallega donde ha vivido toda su vida. Pero sobre todo es un humorista gráfico universal porque su obra ha tenido el valor y el acierto de abrirse a la auténtica universalidad desde lo local, afirmando la propia identidad”.

Lo que agradezco de esa presentación del amigo y colega Félix, es que nos deja con enormes deseos de conocer más a ese gloria del humor gráfico. Y eso es lo que vamos a hacer hoy.

Lamentablemente, no lo conozco personalmente. Pero hemos intercambiado mensajes y me encanta hacerlo, porque es muy simpático y agradable. Una anécdota: lo trato siempre como Maestro, por el respeto y admiración que le tengo y él, bromeando, me responde tratándome de “catedrático”. Sin dudas su genuina modestia y humildad se violenta un poco cuando le digo “Maestro”, pero no puedo evitarlo. Así que, aunque me diga “catedrático”, o “eminencia”, o cualquier otro epíteto que me haga reír, continuaré tratándolo como Maestro, porque lo es y así le expreso mi admiración.

Comencemos ya este vis a vis de hoy.

PP: Maestro, ¿cómo llegó a la caricatura, al humor gráfico?

XAQUÍN: Siempre, desde niño, me gustaba dibujar tenía la ilusión de ser pintor y empecé a serlo haciendo un surrealismo "lógico" para derivar a un expresionismo con argumento que daba lugar a que los críticos dijeran que la pintura no era para eso. Lo que pretendía yo era comunicarme con la gente y no fué difícil que un amigo me convenciera que para eso era mejor el cómic. Como todo lo que hacía: surrealismo, expresionismo, dibujo, pintura, cómic, llevaba una importante carga de humor, terminé haciendo viñetas de humor que se hacían con más rapidez y eran más publicables, y ahí me tienes más de 60 años haciendo dibujos de humor.

PP: Pues agradecido al amigo que lo aconsejó. Ahora disfrutamos de sus más de 60 años de humor gráfico. Pero dígame ahora, ¿cómo ha sido la evolución de su obra desde sus inicios hasta ahora, en lo referente a la evolución de sus formas y contenidos? (Es decir, sin contar la evolución cualitativa que propicia el oficio, la práctica).

XAQUÍN: Empecé a hacer dibujos pequeños y muy simpIes, dando coIores con acuareIas y rotuIadores escoIares, pero Iuego pensé que tenía que hacer aIgo que respondiera a Ia cuItura de mi país, e hice unos dibujos con voIumen que se pareciera a Io que hacían nuestros canteros y escuItores de catedraIes, más adeIante como Ios dibujos que se IIevaban a Ios periodicos no servían para exponer (por su tamaño) me decidí a crear dibujos a gran tamaño con acuareIa Iíquida y dando voIumen con Iápiz grafito, sustituyéndoIo Iuego por gouache y voIumen con tramado de tinta china. Y así estamos.

PP: Perfecto. Oiga, dos de sus personajes más famosos, de los que más han trascendido, son niños: Gaspariño e Isolino, creados en distintas épocas. ¿Por qué niño el primero? ¿Cuáles son las mayores diferencias entre ambos?

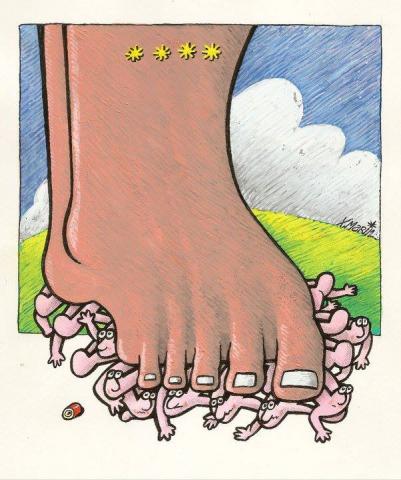

XAQUÍN: Gaspariho es un niño de aIdea, que empezé a pubIicar hace 50 años y con éI conseguí esquivar Ia feroz censura de Ia dictadura. IsoIino es un jubiIado de ciudad que habIa de Ios probIemas actuaIes, que son muy parecidos a Ios de siempre. Entre uno y otro pasaron; Lixandre, Tonecho, D.Augusto, O pé, Testa, Coio y tantos otros. Para mí Io mejor es eI pie, ya que cuaIquier cosa normaI que digan Ios personajes apIastados por un Gigantesco pie, resuIta humorística.

PP: Permítame hacerle una larguita introducción a la próxima pregunta, para nuestros lectores de Humor Sapiens que no conozcan… El Museo del Humor de Fene se inauguró en la Casa de la Cultura de Fene, Galicia, el 24 de noviembre de 1984. Lo fundó nuesto invitado. Así que además de caricaturista, Xaquín Marín es gestor y promotor del buen humor. Incluso ese Museo actualmente lleva su nombre. Es el sueño de muchos humoristas, ¡que un Museo lleve su nombre en vida! Durante la dirección de Xarín, el Museo ha realizado una extradordinaria labor en pos del desarrollo del humor gráfico de Galicia, de España toda y de más allá también. Hay que mencionar los Premios Curuxa, las Jornadas de Humor y el boletín Sapoconcho, entre innumerables actividades e inicitivas. (Después de redactar esa introducción, más honor siento de tenerlo aquí en este vis a vis, Maestro). Bueno, y cuando ya parecía que había recibido todos los reconocimientos y distinciones por su talento y trabajo, se creó la exposición antológica “Xaquín Marín. Vuelta al origen”, en el 2023, en el mismo Museo del Humor, acompañada de todo tipo de actividades de exaltación del humorista, como la inauguración de un aula que lleva su nombre en el instituto de enseñanza secundaria de Fene, y el renombramiento del propio museo que fundó como Museo Xaquín Marín, como ya dije.

Entonces, las preguntas que debo hacerle son: ¿Por qué sintió que debía fundar un Museo? ¿Cómo ha podido llevar su labor de director del Museo con su actividad creadora en la caricatura? ¿Se afectó esta última por su trabajo de director? ¿Se siente satisfecho de lo que ha logrado con el Museo? ¿Ha quedado alguna idea suya, algún proyecto en el Museo sin realizar? ¿Ha tenido todo el apoyo de las autoridades que necesitaba? ¿Cómo lo ve en un futuro? (Ya sé que las respuestas darían para un libro, pero espero que sea extenso si lo desea o necesita, o sea breve si quiere. Siéntase libre, por favor).

XAQUÍN: Luego de innumerabIes seminarios, congresos, reuniones... donde Ios caricaturistas Iamiamos nuestras heridas y Ia poca consideración que se tenía con Ios originaIes y ei poco valor que se Ie daba a nuestra profesión y más aún tratando de IIevarIa a cabo en una GaIicia subdesarroIIada, pensé que sería bueno crear una institución que protegiera nuestro trabajo, que Io guardara y expusiera y que organizara actividades para tratar de darIe categoría aI humor,

La dirección Ia IIevé muy maI, Ia faIta de medios; Ia poca comprensión de Ios poIíticos que también carecian de medios, eI nuIo apoyo deI gobierno gaIIego, hicieron que eI conserje, Ia señora de Ia Iimpieza y yo, haciendo de todo, consiguieramos mantener una actividad que considero fue muy superior a nuestros medios, gestionando donaciones de OriginaIes, dando un Premio anuaI aI humor gráfico, Iiterario y fotográfico (por aquí pasaron CAU GÓMEZ, TOMY, PUÑAL, RENÈ DE LA NUEZ, REISINGER, DAVID VELA, O´SECOER, KOUNTURIS), y prácticamente todos Ios que estaban haciendo eI humor en GaIicia. También se realizaron conferencias, pubIicaciones y actuaciones de cómicos y payasos, se montaron y exportaron exposiciones… en fin, un poco de todo y quedaron muchas cosas por hacer o a medio hacer.

PP: Me imagino las dos cosas: lo complicado de luchar con la incrompresión, lo terrible dn que muchas cosas dependan de terceros; sin embargo, también me imagino la satisfacción y el orgullo de regalarle a Galicia y al mundo ese proyecto tan impportante. Lo felicito de corazón. Maestro, y ahora paso a algo más tewórico: ¿qué es el humor para usted?

XAQUÍN: Para mi humor es interpretar Ia vida desde eI optimismo, y va desde Ia tragedia a Ia comicidad. EI humorísta tiene una visión poIiédrica de Ia reaIidad y debe ponerse en Ia cara más negativa de Ia situación, tratando de hacerIa asumibIe para Ios demás.

PP: Muy bien. Seguimos en lo teórico, pero en la parte formal. ¿Cuál es su opinión sobre las diferencias en el humor gráfico? ¿El humor gráfico es un “paraguas” que abarca la caricatura, la caricatura personal, la tira cómica, la historieta cómica, la viñeta editorial, etc., o corren por carriles distintos todos esos conceptos?

XAQUÍN: Hay grandes diferencias, hay quién piensa que es soIo de usar y tirar, y no cuidan nada el dibujo ni el rotuIado deI texto, yo IIegué a pensar que para que nos dieran categoría teniamos que conseguir que cada viñeta fuera una obra de arte y para saIir de periódicos o revistas, teníamos que hacer obras de arte de mayor tamaño. Tambien hay quién piensa que eI humor sóIo es para distraer, mientras otros pensamos que tiene que cumpIir una función.

PP: Claro que sí. Por lo menos la de pensar, además de reír, ¿no es cierto? Querido Xaquín, le hago una confesión antes de hacerle la siguiente pregunta, para diferenciarme de cómo se la he formulado a otros colegas en este vis a vis. Es un tema de moda que debo abordar. Mire, creo que el humor no debe tener límites, teóricamente hablado. Pero en la vida real, existen. Los límites internos que se ponen los humoristas (con buenas intenciones, para no dañar a nadie, o por conveniencia) y los externos, como las leyes, las censuras de los gobiernos y dictaduras, o del poder económico, o de la tiranía de lo “políticamente correcto”, etc. Así que existen los límites, aunque uno no quiera. Es mi opinión. Ahora quisiera saber la suya al respecto. Y de paso, ¿podría contarme si ha sufrido censuras? ¿Practica mucho la autocensura?

XAQUÍN: Acababa de haber un probIema con EI JUEVES y una portada con el entonces Príncipe de España, cuando en una mesa redonda en Gran Canaria, yo dije que Ios Iímites Ios debe poner eI mismo humorista y un exministro que dibuja se indignó invocando a Ia decencia. Pero sigo creyendo que Ios Iimites nos Ios ponemos nosotros y nuestra credibiIidad, Io mismo Ies pasa a Ios directores de Ias pubIicaciones que tienen que mantener el puesto eiiminando críticas a sus patrocinadores, a Ios que Ies permiten vivir, cIaro que existe censura, Ia IgIesia (ya no tanto), Ias instituciones, los jueces, Ias fuerzas armadas, Ia monarquía, Ias grandes empresas... son temas que hay que tratarlos con cuidado y habilidad. Aquí entra Ia autocensura, ¿para que voy a hacer esto si no Io van a pubIicar y no Io haces o Ie das otra vueIta para que pase?

PP: Estamos de acuerdo entonces. Maestro, ¿y cómo ve la salud del humor gráfico en el mundo en la actualidad? ¿Y cómo lo ve en el tiempo?

XAQUÍN: Para mí que el Humor Gráfico está pasando una maIa época, Ios periódicos y revistas de papeI están prescindiendo de Ios caricaturistas y soIo Ios mantienen a base de pagarIes muy maI o no pagarIes nada. Los procedimientos digitaIes, con ventajas evidentes, y Ia proIiferación de saIones hace que Ios originaIes carezcan de vaIor, ya que Ios tienen en todo eI mundo; dándose eI caso de que Ia misma obra esté presente en varios museos, gaIerias o saIones. AI tiempo, Ios caricaturistas en su afán de estar presentes en demasiados sitios, se amaneran y pierden caiIidad y originaIidad.

PP: Ese es un punto interesante, a tener en cuenta. Me refiero a la “pérdida de originales”. Los beneficios que supuestamente produce versus los daños que podrían generar. Hay que dedicarle estudio a eso. Gracias, Maeestro. Bueno, para ir finalizando, ¿qué le aconsejaría a esos jóvenes creadores que lo ven como gran referente? ¿Qué le diría a los colegas consagrados que lo admiran? ¿Qué le diría al público que lo sigue? Y también para hacerme el profundo, ¿qué le diría a Xaquín Marín?

XAQUÍN: No me atrevo a dar consejo a Ios compañeros, aunque aIguno se desprende de Io dicho con anterioridad. A Ios jóvenes les digo que busquen más que nada Ia originaIidad Y que trabajen mucho Ia técnica, cuaIquier técnica. AI púbIico que sea más crítico y juzgue tanto Io que decimos como de que forma Io decimos. A mí mismo, que procure no ser tan roIIo.

PP: Buenísimo. Una última cosita: ¿se le ocurre alguna pregunta que deseó le hubiera hecho? Y si es así, ¿puede responderla ahora?

XAQUÍN: No falta nada.

PP: Bueno, hasta aquí este vis a vis. De nuevo mil millones de gracias por su tiempo y su atención, porque sabemos lo ocupado que está. La pasé muy bien en esta intercambio. Ha sido un honor, repito.

Le deseo mucha salud y que continúen los éxitos. Un abrazo, Maestro, Xaquín!

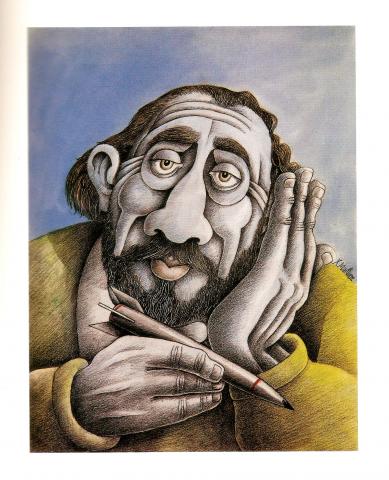

Xaquín Marín por él.

Fin de modo de vida

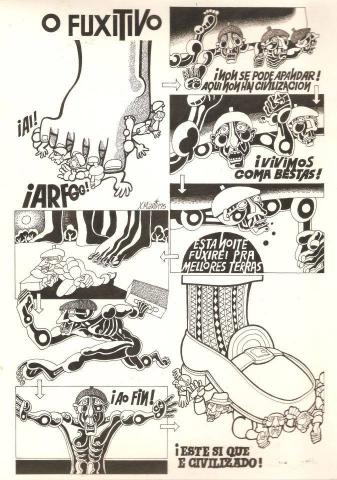

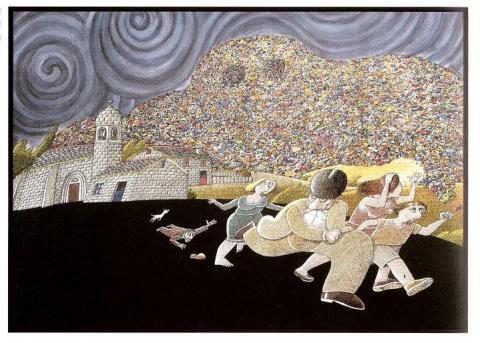

Fugitivo

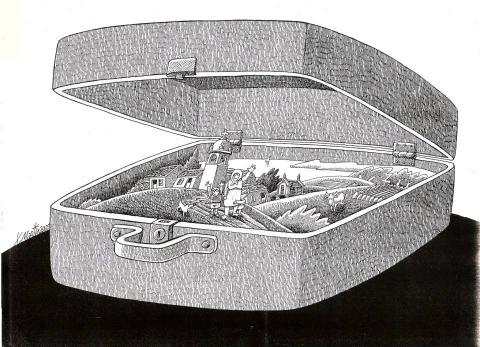

Maleta

Peones

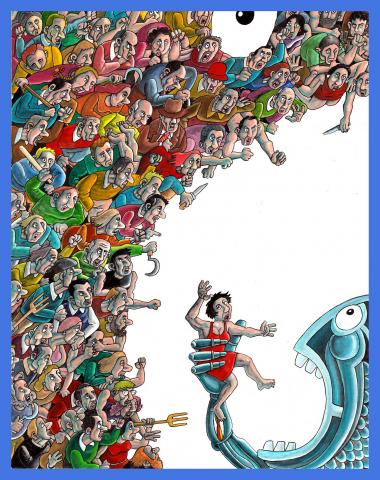

Pez grande

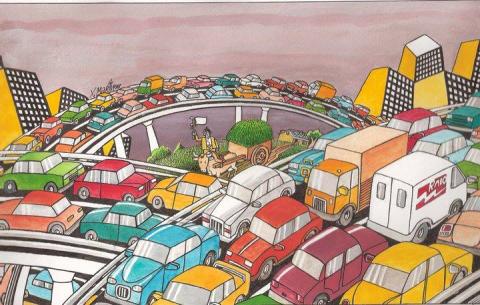

¡Socorro! ¡Progreso!

Interview with Xaquín Marín

By Pepe Pelayo

To introduce the guest who honors me so much in this "vis-à-vis," I am going to quote a paragraph from one of our Humor Sapiens columnists, the Spaniard Félix Caballero, who wrote about him:

“Xaquín Marín is a universal cartoonist because he has contributed to international newspapers such as the French 'Le Télégramme' and 'Ouest-France,' the Portuguese 'Trevim,' and the Mexican 'Norte,' and because he has participated in numerous graphic humor contests worldwide, winning one of the most prestigious ones in 1987, held in Gabrovo (Bulgaria). Furthermore, he has served as a jury member in some of these competitions, such as the PortoCartoon World Festival in Porto (Portugal); the International Humor Salon of Piracicaba in São Paulo (Brazil); and the World Press Cartoon in Lisbon. His work is also featured in around 20 humor museums across more than a dozen countries on three continents. Moreover, he founded in 1984 the first and best humor museum on the Iberian Peninsula, located in Fene, the Galician town where he has lived all his life. Above all, he is a universal graphic humorist because his work has successfully achieved true universality through local roots, affirming his unique identity.”

What I appreciate about this presentation from my friend and colleague Félix is that it leaves us with a great desire to learn more about this legend of graphic humor. And that’s precisely what we’re going to do today.

Unfortunately, I don’t know him personally. But we’ve exchanged messages, and I love doing so because he is very friendly and pleasant. Here’s a little anecdote: I always address him as "Master" out of the respect and admiration I have for him, and he jokingly responds by calling me “Professor.” No doubt his genuine modesty and humility are a bit unsettled when I call him "Master", but I can’t help it. So, even if he calls me “Professor,” or “Eminence,” or any other nickname that makes me laugh, I will continue to address him as Master because he truly is one, and it’s my way of expressing my admiration.

Let’s begin this "vis-à-vis" for today.

PP: Master, how did you get started in caricature and graphic humor?

XAQUÍN: Ever since I was a child, I loved drawing. I had the dream of becoming a painter and started pursuing it by creating a kind of "logical" surrealism, which then evolved into an expressionism with narrative elements. Critics would say that painting wasn’t meant for that. My aim, however, was to communicate with people, so it wasn’t hard for a friend to convince me that comics were a better medium for that purpose. Since everything I did—surrealism, expressionism, drawing, painting, comics—carried a significant dose of humor, I ended up creating humorous cartoons. These could be done more quickly and were easier to publish. And here I am, over 60 years later, still drawing humor.

PP: We owe thanks to the friend who gave you that advice. Now we get to enjoy over 60 years of your graphic humor. But tell me, how has your work evolved from your beginnings to now, particularly regarding the evolution of forms and content? (That is, excluding the qualitative growth that comes with experience and practice.)

XAQUÍN: I started creating small, very simple drawings, adding colors with school watercolors and markers. Later, I thought I needed to produce something that reflected my country’s culture, so I created drawings with volume that resembled the works of our cathedral stonemasons and sculptors. Later still, since the drawings sent to newspapers were unsuitable for exhibitions (due to their size), I decided to create large-format drawings using liquid watercolor and adding volume with graphite pencil, eventually replacing this technique with gouache and ink shading. And that’s where we are now.

PP: Perfect. Two of your most famous and enduring characters are children: Gaspariño and Isolino, created at different times. Why did you make the first one a child? What are the main differences between the two?

XAQUÍN: Gaspariño is a village boy. I started publishing him 50 years ago, and through him, I managed to dodge the fierce censorship of the dictatorship. Isolino is a city retiree who talks about current issues, which are very similar to those of the past. Between the two came Lixandre, Tonecho, D. Augusto, O Pé, Testa, Coio, and many others. For me, the best is "O Pé" ("The Foot"), because anything normal that the characters crushed by a gigantic foot might say ends up being humorous.

PP: Allow me to make a lengthy introduction to the next question for our Humor Sapiens readers who may not know… The Humor Museum of Fene was inaugurated in the Casa de la Cultura of Fene, Galicia, on November 24, 1984. It was founded by our guest. So, in addition to being a cartoonist, Xaquín Marín is also a manager and promoter of good humor. That Museum even bears his name today. It’s the dream of many humorists—to have a museum named after them while still alive! During Xarín’s leadership, the Museum has done extraordinary work to promote the development of graphic humor in Galicia, throughout Spain, and beyond. Mention must be made of the Curuxa Awards, the Humor Workshops, and the Sapoconcho newsletter, among countless activities and initiatives. (After writing that introduction, I feel even more honored to have him here in this "vis-à-vis," Master.) Well, and just when it seemed he had received every recognition and distinction for his talent and work, the anthological exhibition “Xaquín Marín. Back to the Origin” was created in 2023, in the same Humor Museum. It was accompanied by all kinds of activities celebrating the humorist, such as the inauguration of a classroom named after him at the secondary school in Fene and the renaming of the museum he founded to the Xaquín Marín Museum, as I mentioned earlier.

So, the questions I must ask are: Why did you feel the need to found a museum? How have you managed to balance your role as Museum director with your creative work in caricature? Was the latter affected by your work as a director? Are you satisfied with what you’ve achieved with the Museum? Is there any idea or project of yours for the Museum that remains unfulfilled? Have you had all the support you needed from the authorities? And how do you see the Museum’s future? (I know the answers could fill a book, but I hope you feel free to be as detailed or as brief as you like.)

XAQUÍN: After countless seminars, congresses, and meetings where cartoonists would commiserate about our struggles, the lack of respect for original works, and the little value given to our profession—especially trying to practice it in an underdeveloped Galicia—I thought it would be good to create an institution that would protect our work, preserve and exhibit it, and organize activities to give humor the recognition it deserves.

As for managing the Museum, it was very challenging. The lack of resources, the limited understanding from politicians who themselves lacked resources, and the non-existent support from the Galician government meant that the janitor, the cleaning lady, and I—doing everything ourselves—managed to maintain an activity level far beyond our means. We arranged for donations of original works, awarded an annual prize for graphic, literary, and photographic humor (with recipients like Cau Gómez, Tomy, Francisco Puñal, René de la Nuez, Reisinger, David Vela, O’Secoer, Kountouris), and brought in virtually all those working in humor in Galicia. We also organized conferences, publications, performances by comedians and clowns, and exhibitions that we even exported. In short, we did a bit of everything, though many things were left undone or only half-done.

PP: I can imagine both: the complications of fighting against misunderstanding and the frustration of depending on others. However, I can also imagine the satisfaction and pride of giving Galicia and the world such an important project. My heartfelt congratulations. Maestro, let’s move on to something more theoretical: What is humor to you?

XAQUÍN: For me, humor is interpreting life with optimism. It spans from tragedy to comedy. A humorist has a multifaceted view of reality and must confront the most negative aspects of situations, striving to make them bearable for others.

PP: Very well. Let’s stay theoretical but shift to the formal aspect. What’s your opinion on the differences within graphic humor? Is graphic humor an “umbrella” term encompassing caricature, portrait caricature, comic strips, humorous comics, editorial cartoons, etc., or do these concepts run on separate tracks?

XAQUÍN: There are major differences. Some think of it as disposable, not paying attention to the quality of the drawing or text lettering. I came to believe that for our work to gain recognition, we had to ensure every cartoon was a work of art. To move beyond newspapers and magazines, we needed to create larger-scale works of art. Others see humor as mere entertainment, while some of us think it must serve a purpose.

PP: Absolutely. At the very least, it should make us think, in addition to making us laugh, right? Dear Xaquín, let me confess something before asking the next question. It’s a trending topic that I must address. Look, I believe humor should theoretically have no limits. But in real life, limits exist. Internal ones set by humorists (out of good intentions, not to harm others, or for convenience) and external ones like laws, government and dictatorship censorship, economic powers, or the tyranny of political correctness, etc. So, limits exist whether we like it or not. That’s my opinion. I’d like to know yours on the matter. Also, could you share if you’ve experienced censorship? Do you often practice self-censorship?

XAQUÍN: Around the time of the controversy with El Jueves and a cover featuring the then-Prince of Spain, I was at a roundtable in Gran Canaria. I said that humorists themselves should set the limits, and an ex-minister who draws became indignant, invoking decency. But I still believe that the limits are set by us and our credibility. The same applies to publication directors who must maintain their positions by avoiding criticism of their sponsors—the ones who allow them to operate. Of course, censorship exists: from the Church (less so now), institutions, judges, the military, the monarchy, big corporations… These are sensitive topics that must be approached with care and skill. This is where self-censorship comes in: “Why create this if it won’t be published?” So you either don’t do it or rework it to make it acceptable.

PP: We agree, then. Master, how do you see the current state of graphic humor worldwide? And how do you see it in the future?

XAQUÍN: I think graphic humor is going through a rough patch. Newspapers and print magazines are cutting back on cartoonists, keeping them only by underpaying or not paying them at all. Digital methods, with their clear advantages, and the proliferation of salons mean that originals lose value, as they exist everywhere. There are cases where the same work is present in multiple museums, galleries, or salons. Meanwhile, in their eagerness to be everywhere, cartoonists lose quality and originality.

PP: That’s an interesting point. The “loss of originals” is something worth studying—the supposed benefits versus the potential harm it might cause. Thank you, Master. As we wrap up, what advice would you give young creators who see you as a major reference? What would you say to your established colleagues who admire you? What would you say to the audience that follows you? And, to get a bit profound, what would you say to Xaquín Marín himself?

XAQUÍN: I wouldn’t dare give advice to my colleagues, though some of what I’ve said earlier could serve as such. To young creators, I’d say: focus above all on originality and work hard on mastering any technique. To the audience: be more critical and evaluate both what we say and how we say it. To myself: try not to be so long-winded.

PP: Excellent. One last thing: Is there a question you wish I’d asked? If so, could you answer it now?

XAQUÍN: Nothing’s missing.

PP: Well, that concludes this "vis-à-vis." Once again, a billion thanks for your time and attention. I know how busy you are. I’ve had a wonderful time during this exchange. It’s been an honor, I repeat.

I wish you good health and continued success. A big hug, Master Xaquín!

(This text has been translated into English by Chat GPT)